The quiet boating times of the early 1900s are almost impossible to imagine today, their last vestige being yellowed and dog-eared photo postcards from a time when men wore straw boater hats and women wore long white dresses, when boating was nearly as silent as the photographs of it. In those days there were two means of propelling most boats in Nebraska – an oar on the starboard side, an oar on the port side. The only sound was a rhythmic whoosh, whoosh, whoosh.

Nebraskans have always had a powerful affinity for water, particularly for irrigation and power generation. But they also sought water for recreation, perhaps because we are a prairie state, not a water-rich state, at least not on the surface – no seashores, no Great Lakes, not a “Land of 10,000 Lakes.” Nebraska’s only natural lakes were found in the Sandhills, the Rainwater Basin and backwater oxbows along larger rivers. Before 1900, and for some years after, millponds were sprinkled across the state wherever flowing water could be harnessed to power the gristmills used to grind grain into flour. Millponds near small towns and cities were popular for fishing, boating and ice skating; and ice was harvested from many during winter months. Millponds were often sites of summertime Chautauquas – community-based cultural events where lectures, dance, music, drama and other “cultural enrichment” were offered. Many revelers pitched wall tents in tree groves near the water for several days, some for a week or two, and boating was the most popular recreation.

Some small lakes in Nebraska were created specifically for recreation, such as when J.B. Heartwell dammed a small Hastings creek and dredged a lake behind it in 1880. Schimmer’s Lake near the Platte River southwest of Grand Island was even grander. In 1898, Martin Schimmer excavated sand and dirt to construct an earthen and log dam on a diversion of Wood River. Even before the lake’s construction the area was the site of a tavern, hotel and ballroom. Once the lake filled, summer for decades it was the place for Grand Islanders to fish, boat and catch a lake breeze on sultry summer days. A flood washed out most of the dam in 1942 however, and by 1952, Schimmer’s Lake resort passed into history.

Modest, early day impoundments storing water for irrigation also provided recreation, such as Pibel Lake and Lake Ericson in Wheeler County. Small resorts catering to anglers and boaters immediately appeared on the shores of both lakes and others like them across the state. Lake Ericson was created in 1895 by damming the Cedar River to store irrigation water. Stocked by the Nebraska Fish Commission, it was soon full of largemouth bass, including many four- to six-pounders. “Sportsmen began to flock in,” A. Dahl wrote to the Omaha World-Herald in 1903, just after the original dam washed out. “Up till this spring it has been a favorite resort for sportsmen all over the state.” The dam was soon rebuilt, the lake refilled and Lake Ericson became an even more desirable destination, with electric lights, a clubhouse, cottages and campgrounds for “pleasure seekers and anglers.”

GRAND RESORTS

Unquestionably the grandest early day boating resort in Nebraska, challenged only by Lincoln’s Capitol Beach (a natural, saline lake on the western edge of Lincoln), was Carter Lake on the northern edge of Omaha. The large oxbow lake formed when the Missouri River abandoned its former channel and shifted east in the early 1870s. Because state boundaries had already been drawn, Carter Lake, although on the west side of the Missouri River, legally remained part of Iowa. In the late-1800s and early 1900s, it was locally known as Lake Nakomis, Lake Nakoma or Cut-Off Lake. By the close of the first decade of the 1900s and since, it has been called Carter Lake. Even into the early years of the 1900s, Carter Lake was a popular shooting ground for Omaha sportsmen, but as the city crept closer it became a resort for anglers and boaters. In its heyday, Carter Lake was dotted with sailboats, most owned by members of the Omaha Yacht Club, and in the late-1880s with racing boats of the Omaha and Council Bluffs Rowing Association. There were even houseboats and launches powered by inboard engines. Rowboats, though, were far and away the most popular water transportation.

“There is more real outdoor sport out at Cut-Off lake to the square foot than is to be found in about any similar body of water in the world,” Omaha World-Herald sportswriter Sandy Griswold wrote in 1901, “and even yet a comparatively few of the citizens of Omaha know its sources of enjoyment. And yet there are hundreds of sportsmen and pleasure seekers who resort there, even at this early day in the spring and a half day on its classic shores is a treat incomparable. Aside from the shooter there were fishermen, frog catchers and pleasure seekers in flotillas of sail and row boats dotting the waters everywhere, and the scene was as lively, picturesque and interesting as one could well imagine. Often in the cool of an evening young couples go out to Cut-Off and spend an hour or two rowing up and down, happy in their seclusion. Here troths have been plighted and castles built in the air.”

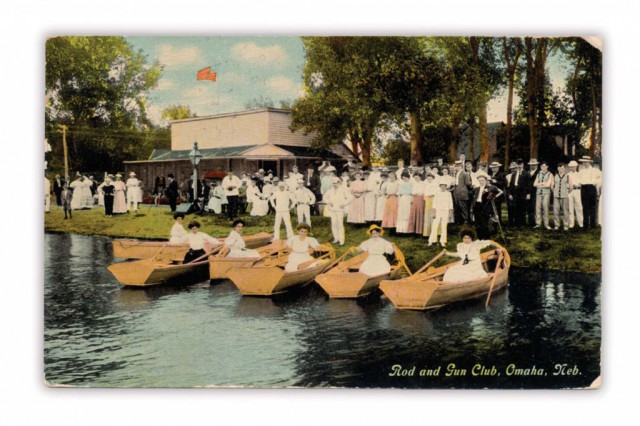

The most prominent stakeholder in Carter Lake boating was the Omaha Rod and Gun Club. “The newly organized Omaha Rod and Gun club is undoubtedly destined to achieve wonders,” Griswold reported in 1905. “Already it is flourishing like a green bay tree and has a membership of 175. The club intends to build a commodious club house at Courtian [Courtland] Beach. It will include boating and bathhouses, shooting boxes and angling facilities and will be modern and up to date in all details.” By 1907, Griswold reported the club had 635 members with 14 sailboats, and motorboats were common.

“There is great activity among the sea dogs at Lake Nakoma,” Griswold wrote in 1908. “Every day when the sun shines hot and when it drops from the zenith, after laboring hours downtown, the busy mariner is putting things in shape for the navigation of the classic waters… On the shore the ship carpenters are hammering away on last year’s craft and the shore cabins are being rapidly reared or transformed into structures of increased comfort and comeliness.”

By the 1910s, Carter Lake’s tranquil waters reverberated with the din of internal combustion engines, both from the large launches and increasingly from small boats powered by outboards. “Few people…realize to what extent motor boating has become in Nebraska,” Fred Goodrich, president of the Walter G. Clark sporting goods house, told Griswold in 1911. “The Rod and Gun club up at Carter lake own scores of them, and every lake in the state of any considerable dimensions is dotted with them.” As the boating season began the following year, Goodrich predicted: “We are going to have our greatest epoch in aquatics on Nebraska waters this summer,” and that “there never was anything like the demand for boats, canoes, skiffs, rowing sculls, yachts, launches and craft of all kinds.” @ Early day boating on Carter Lake and Capitol Beach, though, was the exception in Nebraska. Elsewhere there was not water deep enough or expansive enough for sailboats and launches, nor the urban population to support vendors, and perhaps not the wealth and recreational time for elegant boating found in metropolitan areas. With the exception of millpond rowboating by young lovers, boating across the rest of the state was mostly utilitarian by anglers and waterfowl hunters.

STORE-BOUGHT BOATS

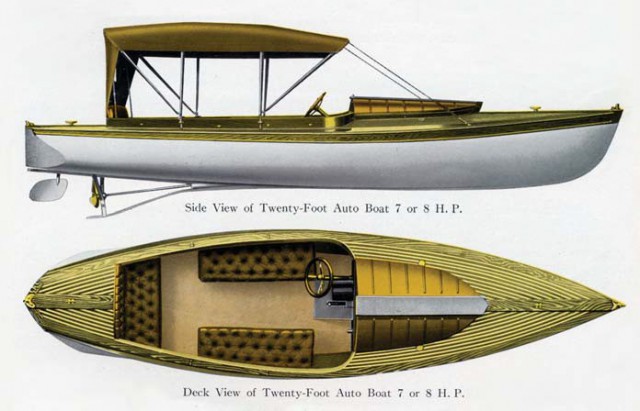

An array of manufactured boats was available during the early 1900s. Among the most prolifically advertised in sporting magazines of the time were the Racine Boat Mfg. Company of Muskegon, Michigan; the Thompson Brothers Boat Company of Peshtigo, Wisconsin, and Cortland, New York (acquired by the Chris Craft Corporation in 1962); and the W.H. Mullins Company of Salem, Ohio. Such companies manufactured and sold everything from canoes, rowboats, 10-foot sneak boats and sailboats to 24-foot launches and 80-foot yachts. Some inboard launches, yachts and sailboats plying the waters of Carter Lake and Capitol Beach during the early 1900s were no doubt manufactured by those companies.

The W.H. Mullins Company produced a full line of pleasure boats, all equipped with “air-tight compartments” making them “virtually unsinkable.” Mullins duck boats were popular with Nebraska waterfowlers and frequently appear in early 1900s photos. Mullins manufactured the 14-foot Get-There Duck Boat ($50 in 1915) with a 36-inch beam and weighing about 85 pounds; and the Bustle ($64 in 1915) that was 10 inches wider, making it “a very steady boat to shoot or cast from.” The 1915 Mullins catalog featured several 14- to 15-foot boats for fishing, each with square sterns to accept increasingly popular outboard motors. The 14-foot Izaak Walton Fishing Boat had both a square stern and bow, and in appearance looked much like today’s aluminum johnboats.

Portability was an important consideration during those decades when roads into the state’s lake country were often little more than trails. Beginning in 1890, the Acme Folding Boat extensively advertised its portable boat in outdoor magazines: “When the ducks are flying, simply strap your rolled-up folding boat to the running board of the flivver – get your gun, boots and coat – and you’re off. When you reach the river or duck pond the boat is ready for the water in a mighty few minutes.” The boat weighed a mere 45 pounds but was claimed to safely carry 600 pounds on the water. Acme’s folding boats were popular enough to spawn numerous other takedown boats from the early 1900s into the 1940s – such as King Folding Boats; the Fellows & Stewart Fold Flat boat; and the Kalamazoo, a canvascovered folding duck boat. One of the most curious takedown boats for hunting and fishing to find its way to Nebraska waters was the three-piece, galvanized iron Taifun boat manufactured by the Alfred C. Goethel Co. of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Weighing slightly more than 100 pounds and 12 feet in length, the front and back sections were sealed air chambers that neatly dovetailed like keystones into the middle section. Water pressure kept the sections snuggly locked together. By the 1930s, even more untraditional boats were being advertised for the sportsman, such as the Inflatex, essentially a rubber raft with “inner tubes of heavy-duty latex rubber” protected by an outer casing of 16-ounce canvas.

Aluminum boats began claiming more of the market following World War II, especially beginning in the 1960s. Alumacraft Ducker Boats were popular with marsh hunters, and some are still being used today on Sandhills lakes. They were advertised as providing “a solid, roomy shooting platform for 2 men,” to be tough enough to break ice, weigh only 67 pounds and “Can’t rot, rust or dry out!” Boats made of plywood also became popular after the war, particularly for pleasure craft, in part because they could be manufactured more cheaply with less skilled labor. Plywood had been around since 1905 but not widely used until the mid-1930s, when a waterproof adhesive was developed. The use of plywood mushroomed during World War II, proving its worth in gliders and PT boats, and after the war for pleasure boat construction.

CHEAPER HOMEMADE

With few exceptions, boats found across Nebraska in the first half of the twentieth century were small, powered by oars and later by small gasoline motors. Particularly in rural areas, many were hand-fashioned. It was common for small town lumberyards to keep their workers busy during slow winter months by building wooden boats for hunters, anglers and resorts. Perhaps nowhere in the state were small boats as extensively used as in the Sandhills lake country. Because most Sandhills lakes are fringed with dense bands of cattail and bulrush, it was, and is, nearly impossible to hunt ducks or fish without a boat. About the only alternative was to run a team of horses into the lake as far as they would go and fish from a wagon (literally a horse-powered boat), which was done on Dads Lake in Cherry County and probably other lakes with firm, sandy bottoms.

During the early 1900s, Sandhills lakes attracted hunters and anglers by the droves from rural towns, from Omaha and Lincoln, and from other states across the country. Few brought their owns boats. From 1900 into the 1930s, hunting and fishing clubs formed on the larger lakes, and maintained their own flotilla. Sportsmen not as well stationed in life rented from seasonal resorts operated by local people. During the early 1900s, start-up ranchers often supplemented their income by accommodating sportsmen, including boat rentals. For a modest fee a rancher or ranch hand could be hired to load boats and sportsmen on a wagon and deliver both to secluded waters. For most it was more convenient and cheaper to rent a boat than to own and transport one. In the early 1900s, for example, boats and a pair of oars were rented for a dollar a day at Wendler’s hunting and fish resort on Rat Lake in Cherry County.

While few locally made boats were comely to the eye, they served their purpose. Most were 12 to 16 feet in length, narrow and nearly canoe-shaped, and were flat-bottomed with a pointed bow and square stern. Typically they were made of cedar or redwood, often with sides fashioned from one board 14- to 18-inches wide, and flooring of two-inch or four-inch boards. Seams were caulked, or tarred with roofing blackjack and covered with strips of galvanized sheet metal held in place with closely spaced galvanized nails. Most were little more than elongated mortar boxes, but they floated and were inexpensive. By the 1920s, commercial metal boats were replacing many wooden rowboats at Sandhills resorts and on other Nebraska waters. Even on big waters like the Missouri River, homemade boats were the rule during the early 1900s, probably for the same reason as in the Sandhills lake country.

“We built‘em out of wood,” Carl “Rudy” Fick (1902-1990) said in a 1988 interview. Fick grew up in Blair, hunting and fishing on the Missouri River and was a state game warden in the 1930s and 1940s. In his youth, and before outboard motors, he customarily rowed three or four miles upstream in the dark to reach his favorite sandbar for waterfowl hunting. “I built my own boats, I could do one in a couple of days,” he said. “The lumberyard here would get us redwood. They’d get ‘em in 20-foot length boards. I worked on the ferryboat when I was a kid and that old guy was a boat builder and he give me my start in boat building. And I built them for a lot of other guys too. I always tried to keep an 18-foot boat, but most of ‘em wanted a 16-foot. There was no metal boats to buy at that time that I know of, so all we had here on the Missouri River were boats that we built ourselves.” Fick’s boats were flat-bottomed, the seams sealed with caulking compound, and then painted. “I built boats from about 1918 on,” Fick said, “until tin boats got popular and then I quit.”

Even though commercially manufactured boats and metal boats became increasingly common on the Missouri River from the 1940s on, hunters and fishermen grudgingly parted with the their locally made wooden boats. Charles Livingston Sr. of Sioux City, Iowa, started hunting the Newcastle area of the Missouri River with his brothers in the 1940s. He said many hunters and fishermen bought their boats from Wayne Ross, a policeman in South Sioux City who built boats on the side.

“He built those boats for years over there in South Sioux,” Livingston recalled in a 1995 interview. “Everybody had ‘em. They were narrow enough you could use oars. The bottom was pretty flat but it flared up, and then the sides would come up to a point. Most of them were 16-foot boats. Nobody had anything bigger in those days. Usually when you took them out of the water over the winter you’d have to fill ‘em up with water and let ‘em swell up again [before using them the next spring]. We run 10-horse Johnson’s on them. Later on we started to put fiberglass on them, went over the wood with fiberglass, but it really didn’t last. You get a little water under it and you had big pieces of it peel off.” Many of Ross’s boats were still running the Missouri River in the early 1960s.

Following World War II, the demand for pleasure crafts mushroomed and boat and outboard motor construction technology moved in new directions. The fine woods once used in boat construction were scarce and expensive and the cost of labor to build them prohibitive, leading to the use of new materials and boats that could be assembled more quickly. Marine plywood finished with waterproof resins became more common, followed by molded fiberglass and plastic.

“THROW THE OARS AWAY!”

Portable boat motors appeared in the United States at least as early as 1896. Cameron B. Waterman assembled his first outboard motor in 1905 using a Curtis motorcycle engine. While functional, it was air-cooled and vibrated excessively. Within two years Waterman had refined his invention and produced 25 water-cooled outboards, essentially the first commercial production of outboards in the U.S. In 1914, the Waterman Porto Motor was advertised as the “most power for the price” and the “most power for the weight.” The 1914 model weighed 59 pounds and was rated at three horsepower. By the end of 1915, his company had sold more than 30,000. By 1921, though, the company was out of business, unable to compete with the new Evinrude outboards.

Ole Evinrude’s inspiration to produce an outboard motor, so the story is told, came from wanting to satisfy Bess’s (then his wife-to-be) craving for a double-dip ice cream cone. Evinrude rowed several miles to an ice cream parlor across the lake from where they were picnicking. Of course the ice cream melted before he returned and his thoughts turned to outboard motors. Evinrude’s prototype motor was a water-cooled, single cylinder, two-cycle engine producing 1½ horsepower and weighing 65 pounds. Production of the Evinrude Detachable Rowboat Motor began in 1909. Later a two-horsepower motor weighing 50 pounds was produced and claimed to push a rowboat at eight miles an hour or a canoe at 12 miles an hour.

Evinrude outboards soon dominated the market. It wasn’t just that their outboards were probably the best on the market, it was the company’s extensive advertising that sold the product. “Don’t row! Throw the oars away!” was the company’s long-running advertising line. Evinrude outboards were not seriously challenged until 1921, when three brothers—Harry, Lou and Clarence Johnson—introduced the lightweight (35 pounds), nearly vibration free, Johnson outboard and pioneered the use of aluminum castings to reduce the motor’s weight.

Nearly from the beginning, manufacturers hawked their outboards as a way for sportsmen to get to the best hunting or fishing places first. A 1912 Evinrude advertisement read: “Instead of tugging at the oars against the waves and current up to where the birds flock, clamp on an Evinrude Detachable Rowboat Motor to the stern of your boat or skiff and get up there easily. You’ll avoid that tiresome rowing up and down, get your blind out earlier, have more time to shoot, follow faster and return quicker—with more birds.” Outboards were quickly adopted by those who could afford them, including Omaha beer brewer Charlie Metz, who was using one on Cody Lake in Cherry County as early as 1913. Rudy Fick, and probably many other Missouri River hunters, bought their first outboard motors in the 1920s. “I had the first outboard motor in Blair, a little old Johnson,” Fick said, “an eight, or nine or 10 horse, something like that. They had ELTO (Evinrude Light Twin Outboard Motor Company, a company started by Ole and Bess Evinrude in 1920 after selling their interest in the original Evinrude company in 1914), and an Evinrude come out before, but they had a rudder on the back, they didn’t turn the whole motor, they weren’t worth nothing, just a little better than nothing. You’d crank them on top, and you always had sore knuckles where it kicked back.” Fick’s first Johnson outboard cost him $180. “They were good motors, those Johnsons, in those days they were the best then,” Fick recalled. “I’d hook it on the side of my old Model T. The door didn’t open on the driver’s side of that Model T, so I could hook it right on there. That’s the way I hauled it. It was handy.”

Outboards were heavily promoted as essential equipment for sportsmen in outdoor magazines, even during the depression years of the 1930s. Sportsmen who couldn’t really afford to buy a motor were even encouraged to “put one on layaway” so they did not need to suffer without. “Sportsmen will no more think of being without a motor than without a fishing rod or gun,” Hugh Grey wrote in the February 1939 issue of Hunting and Fishing magazine. “Today, more and more sportsmen are learning that the outboard motor is no longer the greasy, sputtering imp of a generation ago, but a spotless, gleaming genie which, like the one in Arabian Nights, will do their bidding instantly and silently in response to a rub on the ‘magic lamp’ of the starting handle.” Grey wrote that 75 percent of the craft marketed by boat manufacturers at that time were “designed with the anticipation that they will be driven by an outboard motor,” and “prices have tobogganed until today the cost of a modern outboard is well within the pocketbook of any sportsman.” During World War II, American manufacturers of boats and motors converted to wartime production and the domestic supply essentially vanished. After the war, the public’s pent-up desire for possessions and recreation was unleashed. American sportsmen, now with money in their wallets, scrambled to make up for lost time. Innovations and improvements made during the war immediately found their way into recreational outboards. The 1949 Johnson Sea Horse model QD introduced almost all features found in today’s outboards.

Even in the early 1900s, boats had been designed for, and marketed to, specific buyers – fishermen, duck hunters or general pleasure boaters. After the war outboard motor manufacturers followed suit, although user-specific outboards were usually more packaging than mechanics. In 1955, for example, Evinrude painted their reliable three-horsepower Lightwin motor a “marsh brown” and advertised it as the Ducktwin for duck hunting: “On icy dawns, or when blizzards blow in, it starts – quickly, positively, always!” a 1955 advertisement boasted. “Its specially designed underwater drive lets you smack right through reeds and rushes that would stop any other motor – lets you keep on driving in a few inches of water – wherever there’s depth to float your boat!”

CHANGING WATERS

Not just boats and motors changed over the years, so have Nebraska’s waters. Gone are the millponds of the early 1900s. Gone, too, are the oxbow lakes along the Missouri River, vanished as the floodplain was ditched and drained to create more cropland on the rich and valuable soils; and the large shallow lakes in the Rainwater Basin of south-central Nebraska, lakes large enough that during the 1950s local people waterskied on them. Sandhills lakes remain much as they have always been because the region remains much as it has always been. After decades of exploitation for irrigation water, the interior rivers were even more shallow than they once had been. But new waters appeared, providing boating opportunities formerly unknown in a prairie state like Nebraska. Beginning in the 1940s, rivers were impounded by earthen dams, and behind each dam was an enormous expanse of standing water for boats. Farm ponds proliferated across the state, followed by even larger watershed conservation impoundments.

After World War II, pleasure craft took on an entirely different meaning. There seemed to be few who found pleasure in rowing, far more who found pleasure in power at their fingertips. In the early 1900s only the wealthy could afford launches or yachts powered by in-board gasoline engines. During the 1950s, pleasure craft with ever-larger motors came within the means of many average Americans. Quiet times on Nebraska waters were pushed aside by bigger and faster boats. Recreational boaters came to equate noise with power, and relished it. Airboats now skim at high speed up and down rivers on only inches of water where no motorboat could pass. And in recent decades, personal watercrafts have further detracted from the once peaceful times on Nebraska’s standing waters. Today, few Nebraska’s waters are quiet places where “troths have been plighted and castles built in the air.”

This article originally appeared in the August/September 2007 issue of NEBRASKAland Magazine. Visit the NEBRASKAland Magazine store to order back issues.

Nebraskaland Magazine

Nebraskaland Magazine