Enlarge

By Allison Barg, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Research Graduate Assistant

Read Part I: https://magazine.outdoornebraska.gov/2022/04/a-researchers-field-season-part-i/

Read Part II: https://magazine.outdoornebraska.gov/2022/05/a-researchers-field-season-part-ii/

One of the hardest and most interesting aspects of research is that answering one question generally leads to at least three new ones. For example: What is the best way to count pheasants? Answer: Males crow regularly during the breeding season, so we can listen for those calls and count how many we hear. Easy, right? But to make those counts useful, we also need to know how often they crow; and how their crowing patterns change throughout the season or even throughout the day. Answering these questions can give us an idea of detection probability – how likely it is that a male pheasant will actually crow during our survey if it is present. Without this information, we can’t know how reliable our crow counts actually are.

One way to answer these questions would be to round up a bunch of pheasants, put radio-transmitters on them and have someone — probably me — go find them every day and count how many times they crow, how far apart the crows are, etc. Although this has been done and is valuable research, it’s also incredibly labor and time intensive. Also, it would only tell us about the patterns of those few birds we were able to collar.

An alternative approach, the method I am using, is to use acoustic detectors. These detectors are similar to trail cameras, but unlike game cameras or camera traps that are motion activated and record images, acoustic detectors record sounds. This is what we call a “passive” monitoring technique, because once the detectors are set up, they can be left in the field for several weeks at a time and sometimes even months, depending on storage and battery life. Since there’s no need for a person to be present, acoustic detectors save me a lot of time, but it also means that the only field time I get during this part of the project is at setup, battery changes and when taking them down. I started recording at the beginning of the breeding season, and so far, I have only been out to change the batteries once.

So, instead of walking you through a day or a week to explain this part of the project, like I’ve done with my previous posts, I’m going to go backtrack to the end of March.

March 3, 2022 – Prep Day

There are some types of field work where you can wake up in the morning, grab a backpack and binoculars, and walk out the door. This is not one of them. The tradeoff for spending relatively little time in the field with acoustic monitors is spending lots of time preparing them. For this type of monitoring to work, there are a lot of decisions that need to be made beforehand:

What’s the setup going to look like? Are we attaching them to trees, or do we need to take our own posts? How high do we want to set them up? How many microphones? … The questions go on and on.

For this project, I decided to set the monitors about 3 meters off the ground, high enough to avoid vegetation but low enough to detect ground-dwelling birds. And because these detectors were mostly going into grasslands and wetlands, I wouldn’t be able to count on there being trees to attach them to, which meant that I needed to bring additional equipment.

What time do we want them to record?

This question was easier to address. We are interested in morning crowing patterns, so I set the detectors to record for 5 hours each morning starting at 4:30 a.m.

Which frequency do we want them to capture?

These monitors can be used to capture data on anything from bats to frogs to bird communities, so there are countless configurations of settings to capture exactly what you need without too much ambient noise. Unfortunately, figuring out which configuration will work best for one specific bird call was a challenge, and there’s no way to know for sure that I chose correctly until I get some data. Spoiler: I did not.

Do all of my monitors actually work?

I was fortunate to inherit monitors from a previous graduate student who used them between 2002 and 2005, and I think they have been in a box since. So, the first step in my field preparations was to open up each one, take out old batteries and put in new ones to find out if they were actually operable. Months of outdoor exposure can be hard on equipment, so it wouldn’t have been surprising if a few of the detectors were past usable condition. Thankfully, most of them still worked great.

Once all of these concerns were addressed, I was off to the hardware store. The rest of the day was spent drilling holes in PVC pipes and attaching monitors to plywood boards.

April 2, 2022 – Deployment Day

8:30 a.m. – Assistants Megan Baldissara and Morgan Register are helping me today. We load up the truck with 13 monitors, 13 T-posts, 13 PVC pipes, 1 post driver and 14 individually-prepared field bags with the appropriate number of batteries, U-bolts, straight bolts, nuts, washers, screws and SD cards for each monitor.

You may be thinking, “Alli, why 14 bags? You only have 13 monitors!” Because we were prepared for one of these bags to mysteriously go missing, or fall out of a backpack and into a ravine, or any of the other absurd things that inevitably go wrong in the field. It’s always best to have a backup.

9:30 a.m. – We arrive at the first site in Seward County. The spot I’ve chosen for the first monitor is about a ½-mile hike into a wildlife management area, but we now face a quintessential conundrum for all field researchers: Do we hike all the way around the creek? Or do we take the shortcut of climbing through the creek? It’s dry, and it’s not that steep. We choose the shortcut.

Dear reader, it was not a shortcut. It was fun though.

We finally get to our spot, and one of us gets the post set up while another opens up the monitor to make sure the settings are correct. Then we attach the microphones, make sure the settings are correct again and close up the weatherproof housing. We attach the monitor to the the PVC post, and we’re off to the next location.

11:00 a.m. – Back at the truck. Just 12 more to go …

3:15 p.m. – We found a prairie dog town! Prairie dogs get a bad reputation in some ranching communities, but their towns are incredible little hives for biodiversity, sometimes home to hundreds of different species. So, as an ecologist who’s interested in improving ecosystems, I love to see them. However, their presence does cause one little problem: Prairie dogs are LOUD, and I’m not in love with the prospect of having to listen to hours of audio recordings of prairie dog squeaks while hoping to find a pheasant crow. So, I’ll hike a little farther to setup this monitor.

May 7, 2022 – Battery Checks

After about a month of being in the field, it’s time to change the batteries in my monitors. This is exciting because it also means I get to change out the SD cards and see what kind of data I’ve been getting.

10 a.m. – Monitor No. 1 has already died, which isn’t a great sign because the batteries really should have lasted another week or two. This tells me that it was probably triggered to record more often than I expected, which might mean I’ve captured a lot of ambient noise. I came prepared for this and have my laptop with me so I can immediately see what kind of data the monitors have been capturing. This allows me to make immediate setting adjustments without having to make a second trip. The software I use is called Kaleidoscope, and it enables me to view and listen to a few of the recordings from each SD card quickly in the field. Also, the software makes it easy to see whether the majority of recordings are birdsong or just irrelevant noise without having to listen to the whole thing.

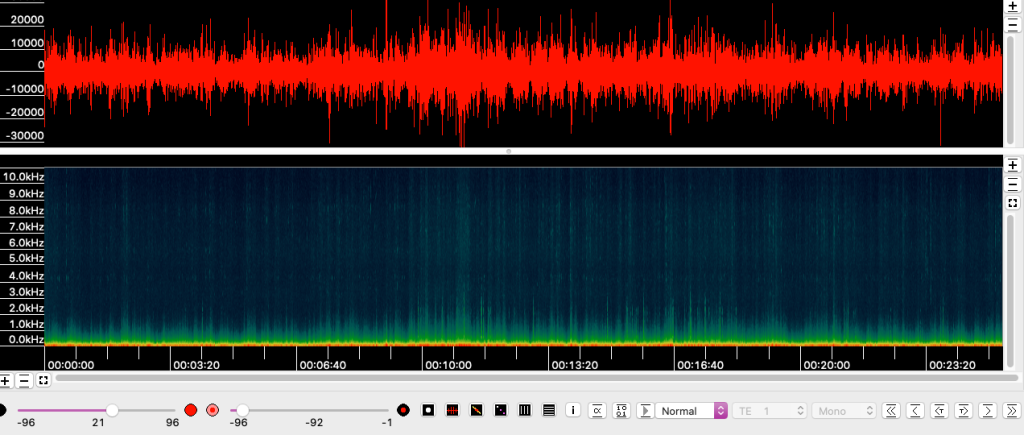

And I was right – I’ve got hours and hours of wind. That’s right, a month of recording, and it seems that most of it is wind. The lack of any discernible variation in the recording below is indication that this whole recording will be noise. Although there may be recordings in here that have actual pheasant data, it’s just going to be harder for me to find them. So, I change a few settings on the monitor that will hopefully fix the problem, put in new batteries and SD cards, and we’re off to check the next monitor.

11:30 a.m. – OK, monitor No. 2 did not die, which is a good sign, and so far, it looks like it’s full of actual bird calls. Below is the first recording, and you can see that there are several distinct crests and troughs in the graph, which is a good indication that we’ve got bird song. The pheasant crow is in the white box.

Listen to the audio clip of this segment here. You can hear the pheasant crowing right before the 2-second mark:

3 p.m. – Well, despite checking the weather on multiple weather apps before I left, it looks like I’m about to get caught in a storm. And because walking through a wetland in a storm to handle electronic devices attached to tall metal poles feels like a poor choice, I’m calling it a day.

About Allison Barg

Allison grew up outside of Mead, Nebraska, and received her bachelor’s degree from the University of Nebraska – Lincoln in fisheries and wildlife in 2016. After several years working on research projects on everything from bats to sea turtles, she returned to school to earn her master’s degree in wildlife management and conservation from the University of South Wales. Allison’s master’s research was based on western polecats and their interactions with road systems. In 2021, Allison moved back to Nebraska to begin her PhD at UN-L where she works in the Applied Wildlife Ecology and Spatial Movement (AWESM) Lab.

Allison grew up outside of Mead, Nebraska, and received her bachelor’s degree from the University of Nebraska – Lincoln in fisheries and wildlife in 2016. After several years working on research projects on everything from bats to sea turtles, she returned to school to earn her master’s degree in wildlife management and conservation from the University of South Wales. Allison’s master’s research was based on western polecats and their interactions with road systems. In 2021, Allison moved back to Nebraska to begin her PhD at UN-L where she works in the Applied Wildlife Ecology and Spatial Movement (AWESM) Lab.

Nebraskaland Magazine

Nebraskaland Magazine