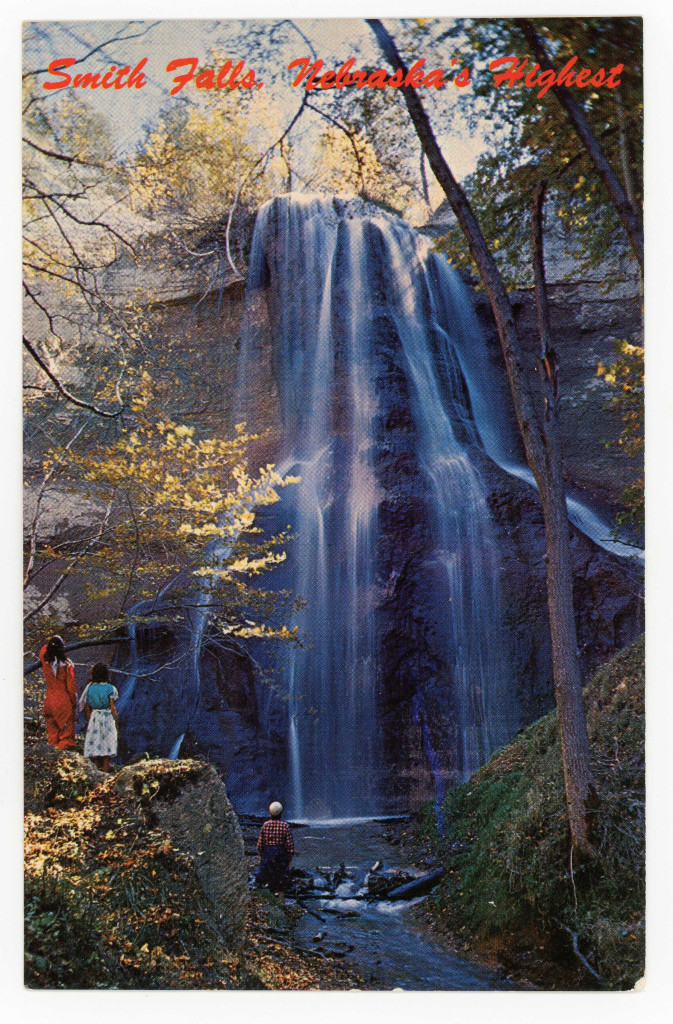

More than 230 waterfalls adorn the Niobrara Valley, but one state park attraction still stands above them all

Enlarge

Photo by Justin Haag

Story and photos by Justin Haag

It’s reassuring to return to places that don’t change much over time. While such can be said of other Nebraska rivers and streams, there’s something exceptional, and especially enduring, about this spot tucked away in a canyon 250 yards from the Niobrara River. A place where one can rely on the water flowing from more than 60 feet overhead and splashing into the shallow pool below. Where children can stand below the towering waterfall on a hot day, feeling the force of cold water rush over their bodies just as generations have before them, their shrills barely audible over the roar of the natural spectacle itself.

Even though Smith Falls State Park between Valentine and Sparks is Nebraska’s youngest, the property’s main attraction has surely been recognized as a scenic jewel since its discovery by humans, whenever that may have been. An early 1900s newspaper account said Native Americans had referred to it as the “Place of the Roaring Water,” reporting an initiative to have it named Roaring Falls.

The waterfall was instead known to the settlers of the times as Arikaree Falls. The name is a reference to the Arikara, the semi-nomadic tribe of Native Americans that has a rich history along the upper Missouri Valley and migrated to northern Nebraska for about a decade in 1823.

Regardless of its name through time, the roar has always been the same.

‘Fred’s Falls’?

In 1896, when Frederic Smith obtained the first homestead patent for land on which the waterfall resides, the attraction gradually became known locally as the “Smith fall,” a description that eventually became a proper noun. Early newspaper stories also refer to it as Honey Smith, or Hunney Smith, Falls.

Later, under the ownership of another “Fred,” Smith Falls gradually picked up steam as the tourist attraction we know today.

In 1941, Sandhills farmer-rancher Fred Krzyzanowski bought the property for $7 per acre as a place to graze cattle, reportedly not knowing there was a waterfall on it. He owned the property a month before visiting the falls.

With vehicle access to the falls locked behind private lands on the south side of the Niobrara, Krzyzanowski allowed the increasing number of people floating the river to park their vessels for a visit. He later catered to the falls’ popularity by adding a campground and picnic tables. Visitors shared space with his cattle herd.

In 1983, Krzyzanowski began charging 50 cents for those arriving by raft or inner tubes and $1 for canoeists, with proceeds used for trash clean-up and the installation of outhouses.

Visitors also could pay 50 cents for a ride across the river on the “cable car.” It’s not a cable car resembling those carrying passengers around San Francisco. Instead, it’s something of a gondola lift — a steel cage hanging on a cable spanning the river with pulleys fashioned from car wheels. The car, powered by hand pedals, was initially constructed by Cherry County for Krzyzanowski’s daughter, Margaret, to get from their home on the south side of the river to meet the school bus on the north side. Even though Margaret tragically died from illness 18 months after the car’s installation, the lift remained as a landmark for people floating the river.

The cable car’s origins were among the stories visitors to the falls remember Krzyzanowski telling them as he visited the campground. The contraption has been closed to use, but still exists in place for posterity.

Krzyzanowski died at age 89 in August 1988. In 1990, the Krzyzanowski family contracted a private lease agreement for management of the camping facilities, known as “12 Mile Camp.” Not long after, the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission entered the picture.

Becoming a State Park

In January 1992, after considerable discussion, the Game and Parks Commission OK’d a 30-year lease agreement with the Krzyzanowski family for 244 acres on both sides of the river. The agency agreed to pay $10,000 per year and planned more than $500,000 of improvements for when the property officially became a state park that May.

One of the first priorities was the path to the big waterfall. With increased traffic, officials realized the need to improve safety and reduce erosion caused by the wet feet trekking up and down the single-track dirt trail to the attraction.

With volunteer assistance of more than 100 members of the Casper Yost Chapter of the Telephone Pioneers of America, a wooden walkway, supported by 180 4×4 posts, was installed in 1993. Safely suspending visitors about 4 feet above the old dirt trail, it was christened the Fred Krzyzanowski Memorial Walkway.

Bridging Gaps

Another goal of Game and Parks when assuming management of the park was to make the falls accessible to more people.

The same month Game and Parks commissioners approved the lease agreement for Smith Falls in 1992, Knox County commissioners decided a 165-foot high-truss steel bridge at the north side of Verdigre had become insufficient after seven decades of use and would have to come down for a replacement. What was deemed by many in the Verdigre area to be a sad event for the stately landmark now seems more like destiny than coincidence.

The bridge was retrieved from the county’s scrap heap and transported to the fledgling state park to be reassembled and gain new life as a footbridge. The 30-ton structure, originally constructed in 1922, was assembled by contractors and put in place Oct. 1, 1996, with three giant cranes and a bulldozer. Most of the project’s $340,000 cost was paid for with federal grant money, most notably the Transportation Enhancement Program.

The bridge was amply sturdy enough to get park visitors across the river by foot, planners noted, and would even complement the area’s aesthetics. During reassembly, it was narrowed by 5 feet, making it even stronger than its 5-ton capacity when it spanned Verdigre Creek.

For the first time, the public could visit Smith Falls without floating, wading or riding the rusty cable car across the river. The Verdigre Bridge has since served countless visitors, throughout all seasons, who otherwise might not have been able to see the attraction.

A New Chapter

Through the years, the park renovated the visitors center and added 70 primitive campsites, a shower house, two picnic shelters, four restrooms and housing for the park superintendent.

With the end of the 30-year lease agreement looming in the 2010s, many wondered if the park’s future was in peril. They were relieved when the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission and the Krzyzanowskis — Fred Jr. and wife Joann still farm and ranch on land neighboring the park — renewed the lease agreement for 25 more years in 2018.

Since then, Game and Parks has been investing in substantial improvements.

The wooden walkway to the falls had served the park well but was showing wear from three decades of use and exposure to the elements.

In May 2023, after eight months of construction, the Game and Parks Commission opened an improved walkway with composite decking. The project of more than $800,000 was largely funded with a source not available when the first walkway was built. The Capital Maintenance Fund was established by the Nebraska Legislature in 2016 to help preserve Nebraska’s public outdoor recreation facilities and parklands.

The new 500-foot walkway features both a wheelchair ramp with a gradual grade and a more direct route via steps. With its steel posts and frame, concrete footings and aluminum railing, the new walkway is expected to last much longer than the one it replaced. A deck of similar materials was constructed at the park’s visitors center, with new steps leading to the campground. Also included in the walkway project were wheelchair-accessible approaches to the footbridge.

Game and Parks is in the process of developing a management plan for the park, and officials expect many exciting developments in coming years.

A Natural Marvel

A goal for Game and Parks since the beginning has been to balance accessibility with preserving the area’s natural attributes. There’s a lot to consider in what has been designated the Middle Niobrara Biologically Unique Landscape by the Nebraska Natural Legacy Project. Six natural ecological cultures meet in this area, resulting in a fascinating mix of plant and wildlife species.

As warming temperatures caused glaciers of the area to retreat about 10,000 years ago, some botanical species survived in the steep, shaded canyon of the Niobrara that don’t survive on the warmer lands above. The park is home to the Smith aspen trees, an endemic hybrid of bigtooth (Populus grandidentata) and quaking (Populus tremuloides) aspen. Attractive paper birches also adorn the park. People aren’t sure for how long, though, because they aren’t reproducing.

Because of the sensitive biological attributes, the park limits hiking to designated trails and walkways. The best way for visitors to take in the park’s natural scene is the Jim MacAllister Nature Trail, named for one of the Game and Parks officials who was instrumental in the park’s early development. It takes hikers 11⁄2 miles from the bottom of the canyon to the top. It’s an elevation change of about 200 feet, but most hikers consider it easy.

Along the way, the trail encounters a number of the other nine waterfalls in the park and 230-plus waterfalls documented in the Niobrara Valley. Most other falls in the park are not marked and are much smaller than Smith. They include Turkey Feather, Birch, Pine and Little Smith falls.

A Popular, Quiet Place

A summer day at Smith Falls State Park evolves from a tranquil night and sunrise to the chatter from a steady stream of floaters landing riverside to take that walk up the canyon for a scenic view or cold shower from nature.

Those floating the river can access the park at two landings. The Smith Falls Landing is on the south side of the river and the Nichols Landing at the north side, just east of the campground.

In the late 1980s, officials estimated 15,000-20,000 canoers per year on the river. The National Park Service estimates the latest five-year average to be about 75,000 floaters per year, surely driven by increased publicity and the popularity of float tubes and kayaks. In 2020, when much of the world was shut down because of the pandemic, the figure topped 100,000.

Despite all of that busyness, Smith Falls and the Niobrara River maintain a reputation of serenity.

Smith Falls was among the stops that a team for Quiet Parks International made while doing acoustic tests on a four-day kayak trip down the river. The organization bestowed the river with its “Quiet Trail” designation in 2023 — the second in the world and first in North America to receive such an honor.

That doesn’t mean Smith Falls is necessarily quiet. Those doing the sound study for the designation didn’t document a figure, but said the water dropping at Smith Falls is probably about 70 decibels, comparable to that of a vacuum cleaner.

A Niobrara Valley Treasure

Early news accounts tell of the beauty of at least four other named falls in the area surrounding Valentine that since have been concealed behind the fences of private landowners. The one that is now the main attraction of this state park was and remains to be the most well-known.

The immeasurable value of Smith Falls was often mentioned in the 1970s and 1980s as contentious debates raged over a proposed dam project and federal legislation to designate the Niobrara a national scenic river. Although the proposed dam site was downstream near Norden and said by proponents not to affect Smith Falls, the beauty spot surely was present in the minds of the public during the discussions. The dam proposal failed, but the National Scenic River designation passed in 1991. The designation has afforded certain protections from development to 76 miles of the river that includes the park.

Roaring On

The water of Smith Creek emerges from a spring of the Ogallala Aquifer about 800 yards south of the waterfall. Because of the stream’s short length, it’s much less susceptible to the water fluctuations of longer creeks and rivers. Smith Creek’s consistent 50-degree water, with an average flow of 2.59 cubic feet per second, satisfies visitors year-round. Inch-for-inch, it surely gets more people wet than any other natural tributary in the state.

While the fall may seem consistent within our lifetimes, it’s constantly changing, as with all stream systems, and is in the stage of a geological cycle.

The geology of the Niobrara Valley gives its waterfalls a notable characteristic. Smith Falls and others in the valley are convex, meaning the water flows over the top of a face that protrudes outward from the center.

In winter, the sides of Smith Falls and others often become adorned with attractive icicles while the spring water continues to flow through the center. As groundwater in the sandstone at the sides freezes and thaws, it loosens the material and makes it subject to erosion.

Darryl Pederson, a professor emeritus at the University of Nebraska who has extensively researched waterfalls, said someday Smith Falls will look much different. Eventually, the water will veer to one side of the rock protrusion instead of flowing over the top of it. Then, the protrusion itself will no longer be protected by the spring water and will be subject to freezing, thawing and breaking up.

As it stands, though, Smith Falls is a point of pride for Nebraska, and many say it holds its own on a larger scene.

“Niagara appeals to you by its grandeur, but the Arikaree by its dainty beauty far surpasses any other falls on the continent,” a newspaper reporter wrote in 1908.

Thanks to the many improvements to the state park, more people are enjoying the “Place of the Roaring Water” than ever before. And, with each passing day, the water continues to fall for whomever wants to see, feel and hear its timeless charms.

How High is It?

For as long as people have written about Smith Falls, they’ve been assigning a number to its height. It’s been reported as high as 100 feet tall but is usually listed between 60 to 75 feet.

The first “official” measurement — 68 feet — is believed to have been made by Dr. George Condra of the state conservation and soil survey in the 1910s.

For uncertain reasons, the official height has changed since then. The National Park Service reports that it was last measured to be 63 feet. Park service employees plan to join Game and Parks and other partners in measuring the falls again this year using a process that involves a rangefinder, clinometer and knowledge of trigonometry.

Nebraskaland Magazine

Nebraskaland Magazine