By Julie Geiser

Once regarded as the most popular of all game fish, the rainbow trout still has a big presence in Nebraska waters. In the early 1900s, trout were not only a staple food source for many but also an esteemed sport fish for anglers. Because of this popularity, ideas began to form at the Nebraska Bureau of Fish and Game, now the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, about growing rainbow trout.

Then, in 1924, the Bureau purchased 20 acres of land north of Parks for a new hatchery for $4,500. Fed by Rock Creek, a series of the largest and coldest springs in Nebraska, the Bureau planned for this new hatchery to supply the entire state with trout.

It was a lofty goal that quickly gathered steam.

The Beginnings

H.P. Runion was a rancher and owner of a hatchery at Benkelman until it was purchased by the Bureau in 1919. Runion raised many fish at the Benkelman hatchery and sold them to the state. But he thought more could be done and done better. Years before, around 1911, Runion began a nursery pond experiment at Rock Creek back when the crystal-clear waters of Rock Creek served as a watering area for thirsty cattle.

Runion found out the water and vegetation at Rock Creek were ideal for newly hatched trout fry and that they thrived and grew rapidly in the clear, cool, flowing waters at Rock Creek. Coming from the notion of rearing trout and other fish to a fingerling size before releasing them into wild waters, giving them a better chance of survival, these features made Rock Creek seemingly exceptional for a fish hatchery.

Getting a hatchery at Rock Creek did present challenges, however. The State Fish Commission in Lincoln claimed there wasn’t enough water flowing in the creek to support a trout-rearing facility, dismissing the idea of a hatchery in that part of the state.

Frank Richardson, a Benkelman resident and hatchery supporter, challenged the Commissioners to travel the 300 miles to Rock Creek to take a look. If they still claimed the creek didn’t produce enough water, Richardson would pay their travel expenses, buy them a steak, and put $10 in each of their pockets — a substantial amount of money at that time.

After making the journey and seeing Rock Creek’s potential, the Commissioners vowed to build a trout facility there. Shortly after, Gov. Charles W. Bryan visited the area and was also supportive of this idea, helping push the hatchery through during his first term in 1923.

Construction soon followed.

Construction and Expansion

With construction well underway in 1926, Harry Runion was appointed superintendent to Rock Creek along with running the nearby Benkelman hatchery. A facility with the capacity for hatching several million trout eggs a year was built, along with a residence for a caretaker, a barn, several small holding ponds and other buildings. New ponds were in the works to be built as there were more fish that could be hatched than there were nursery ponds to put them in.

The Bureau purchased 87 more acres of land for Rock Creek hatchery in 1927 for $6,500. An icehouse and a new road were built along with more nursery ponds.

By the summer of 1927, 42,000 largemouth bass fingerlings had been raised in the small pond, supporting the idea that conditions at the hatchery were ideal for both bass and trout rearing.

But the Bureau sought even more success. At the time, there were few facilities available to hold fry and raise them to a larger size prior to stocking. It was estimated that only about 5% of trout raised ever reached maturity or were available for anglers to catch. The Bureau’s plan was to keep the fish in the nursery ponds from spring to fall so they had time to grow into fingerlings and increase their chances of survival. They would distribute less fry and more fingerling-sized fish to Nebraska’s lakes and streams, which meant more rearing ponds and nurseries were needed.

Rock Creek would help this policy by building more ponds for trout and bass, but more were needed to satisfy the growing demand of fish by anglers. To help supply fingerling fish, private fish culture was encouraged by the Bureau. Chapters of the Izaak Walton League built nursery ponds and were a big supporter of raising the larger fish. The goal was to have excellent trout fishing in approximately 65 streams across western and northwestern Nebraska.

By 1929, four new ponds were added at Rock Creek, a bridge was constructed across the creek leading to the hatching ponds and several retaining walls were built on the ponds. Three concrete spillways were constructed, and sewer pipe was laid.

A modern fish hatchery was constructed for $6,000 in 1930. At the time, this was one of the most up-to-date hatching houses in the country and had the capacity to hatch 1.5 million eggs. The old hatch house was then turned into a residence for hatchery staff. The hatchery was said to have 31 ponds of varying sizes from the small nursery ponds to the main lake that took up 16 acres on the property.

Statewide, fishing became increasingly popular. As roads were developed and cars became a household staple, more people were traveling to fish. This also meant fish production and transportation of the fish would have to change with growing needs.

By 1940, the Commission’s number of adult fish for spring stockings was increased by about 30 percent from the year before. However, at this point, Rock Creek’s maximum capacity levels had been met, and if more fish were to be produced there, the hatchery would need to be expanded.

To meet this demand, the largest spring at Rock Creek was evaluated. This spring sat about 3,000 feet above the hatching house and that water was running into the creek, meaning the flow of 2,000 gallons of water per minute was not being utilized.

To tap into this unused water supply, an 18-inch concrete pipeline to a surge tank near the hatching house and a group of circular pools were constructed for growing adult trout. By doing this, up to a quarter million adult trout could be grown at Rock Creek annually.

A Relentless Task

Feeding the fish at Rock Creek was a relentless task. In the early years, trout were fed liver; staff would walk from pond to pond with a kitchen cheese grater and beef liver, scraping off chunks of meat into the water as they went. As the trout grew and required larger pieces of liver, the grater was turned over and the cabbage shredder side of the utensil was used.

As more fish were reared, more food was needed, and the hatchery turned to horse meat that was butchered in Benkelman and ground up at the hatchery. Sometimes, the meat arrived spoiled and infested with maggots, which would later become an innovative way of feeding the fish.

Frank Weiss, the new superintendent, discovered that trout loved maggots and seemed to thrive on them. So, he designed a wooden box with a hail screen, a galvanized wire mesh covering, on the top and bottom and suspended them over the ponds. “We’d shoot a few jackrabbits and put them in the boxes and leave the rest to the flies,” he stated. As the maggots developed, they’d drop from the box and the trout fed on them.

During World War II, finding fish food meant coming up with different sources. Weiss began seining carp from area lakes, transferring them to hatchery ponds. The carp were then seined again when needed as food. They were frozen overnight and run through a large meat grinder.

From 1943 to 1945, trout production was dramatically impacted at Rock Creek due to the lack of meat products for feeding the fish and the lack of labor in the area because of the war. Weiss was pretty much a one-man-show at the hatchery. If it wasn’t for the help from anglers and his family, production would have been cut back even more.

After 24 years of grating liver, grinding horse meat and carp and propagating maggots, Weiss came up with another solution to feeding trout, with its principles still used in hatcheries today. Weiss began experimenting with a dehydrated cereal pellet.

Previously, the cereal was in powder form, but Weiss found that when beef melt, which is beef pancreas, is ground with fish cereal, it makes a nice floating fish food that sinks slowly, giving trout a chance to eat it before it reaches the bottom.

Ground liver was still used along with the new concept of floating fish food at Rock Creek until the late 1970s. Nowadays, most hatcheries exclusively feed trout floating fish food.

If It Works …

Rock Creek Hatchery has produced millions of fish for Nebraska anglers to catch. In 2024 alone, Rock Creek Hatchery was scheduled to stock more than 92,000 rainbow trout and 2,500 tiger trout.

The hatchery has also produced many other species of fish. Everything from rock bass, redear sunfish, crappie, largemouth and smallmouth bass, bluegill, channel catfish, yellow perch, brown trout, brook trout, wiper and grass carp have been raised there. Even Kokanee red salmon were hatched in 1958 and released at Lake Ogallala.

Today, the modern hatch house that was built in 1930 is still being used along with 16 ponds for fish production. While much of the hatchery resembles its 1924 beginnings, there were obstacles to overcome and modifications made in trout rearing.

Improvements at the facility over the years include new and additional trout troughs in 1950 that would produce almost 600,000 brown and rainbow trout eggs, over 200,000 more than before the addition.

By 1976, it was feared that the cold, clean water flows at the hatchery would be greatly reduced because of the large number of irrigation wells that were put in near the hatchery for center-pivot systems, and a new hatchery may need to be built. After studies were completed, geologists found that if the water flow was greatly reduced, more water could be obtained by installing high-capacity pumps and wells.

In 1980, more than $200,000 was spent modernizing the hatchery, with raceway, piping system, water reservoir, and aeration system improvements, along with new wells, to pursue the science of raising trout.

Since then, much of what worked the past 100 years still works, as seen from the thousands of fish stocked each year. Which is why if you’ve fished for trout in Nebraska in the last century, chances are you’ve landed one raised at Rock Creek Hatchery.

Fish Cars

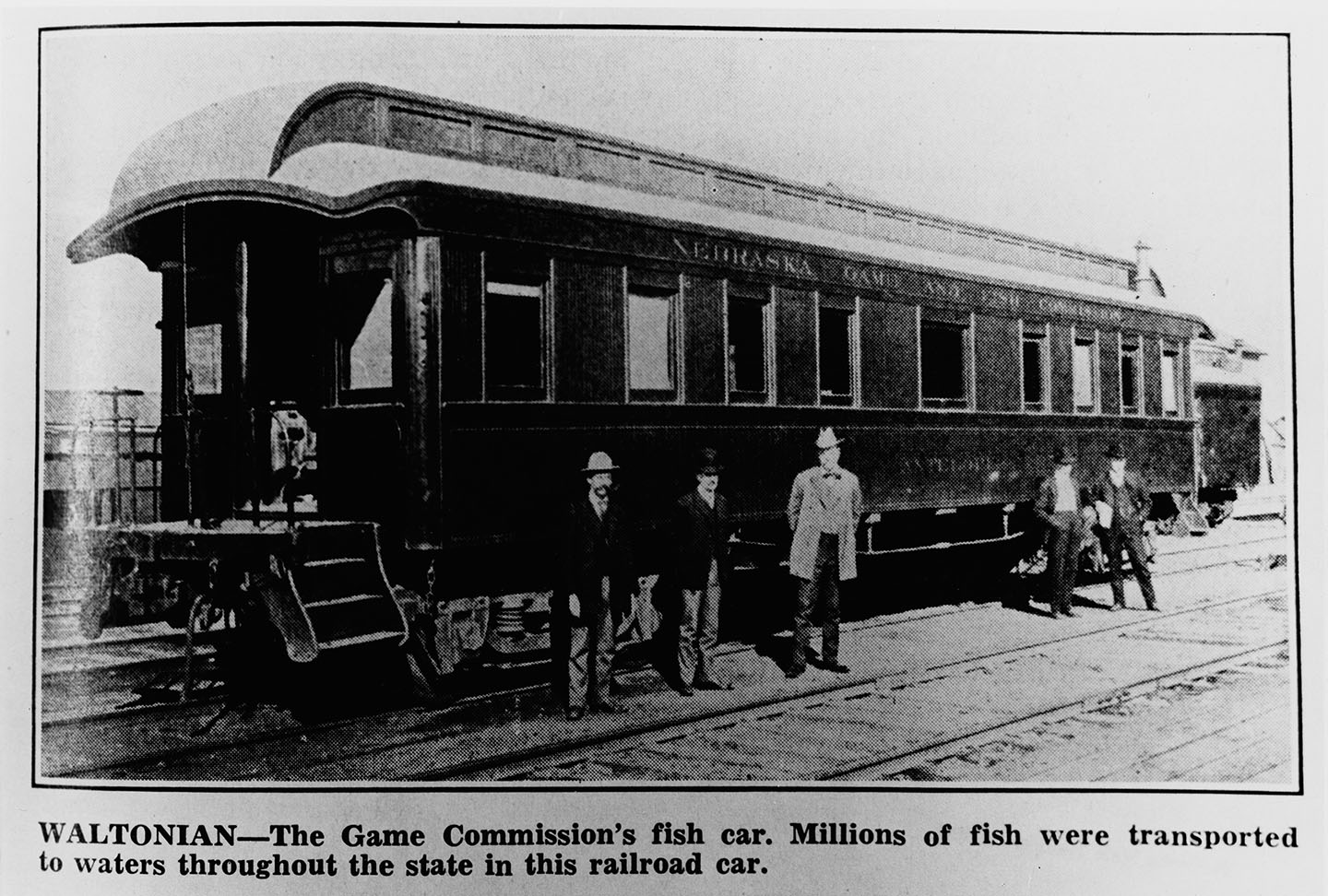

Fish cars were used on railways to carry eggs from other states, such as Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri and Wisconsin, to Nebraska. These cars were the best in service at that time, made specifically for hauling fish long distances. Equipped with fish tanks instead of seats, water was kept running over the tanks to keep the air supply at appropriate levels for the fish. There were also living quarters on board for fish crews.

The Antelope was the first fish car to service Nebraska in 1889. It was a wooden-framed car and would eventually be replaced by a modern metal car. The Angler was the original name of Nebraska’s second fish car, later named the Waltonian. This car serviced Nebraska and Rock Creek with fish deliveries until around 1931.

When the trains stopped at a depot or near a stocking location, fish were taken off the fish car and transported the rest of the way by horse and cart in milk cans, by baggage or other means of less-than-superior transportation over sometimes undeveloped terrain.

Fish rearing evolved, and fry were no longer taken from hatcheries and dumped into lakes, ponds and streams. Instead, they were placed in nurseries where food was abundant and they could grow to larger sizes.

The fish cars would eventually be replaced by trucks, increasing stockings from 10-15 per day up to 50 at about the same cost. By 1930, a fleet of fish trucks equipped with ice and oxygen were placed into service.

Making Trout

While some of the eggs used at Rock Creek are obtained from federal hatcheries and fertilized before being shipped, quite often biologists, with a squeeze from their hands, start the process of making trout.

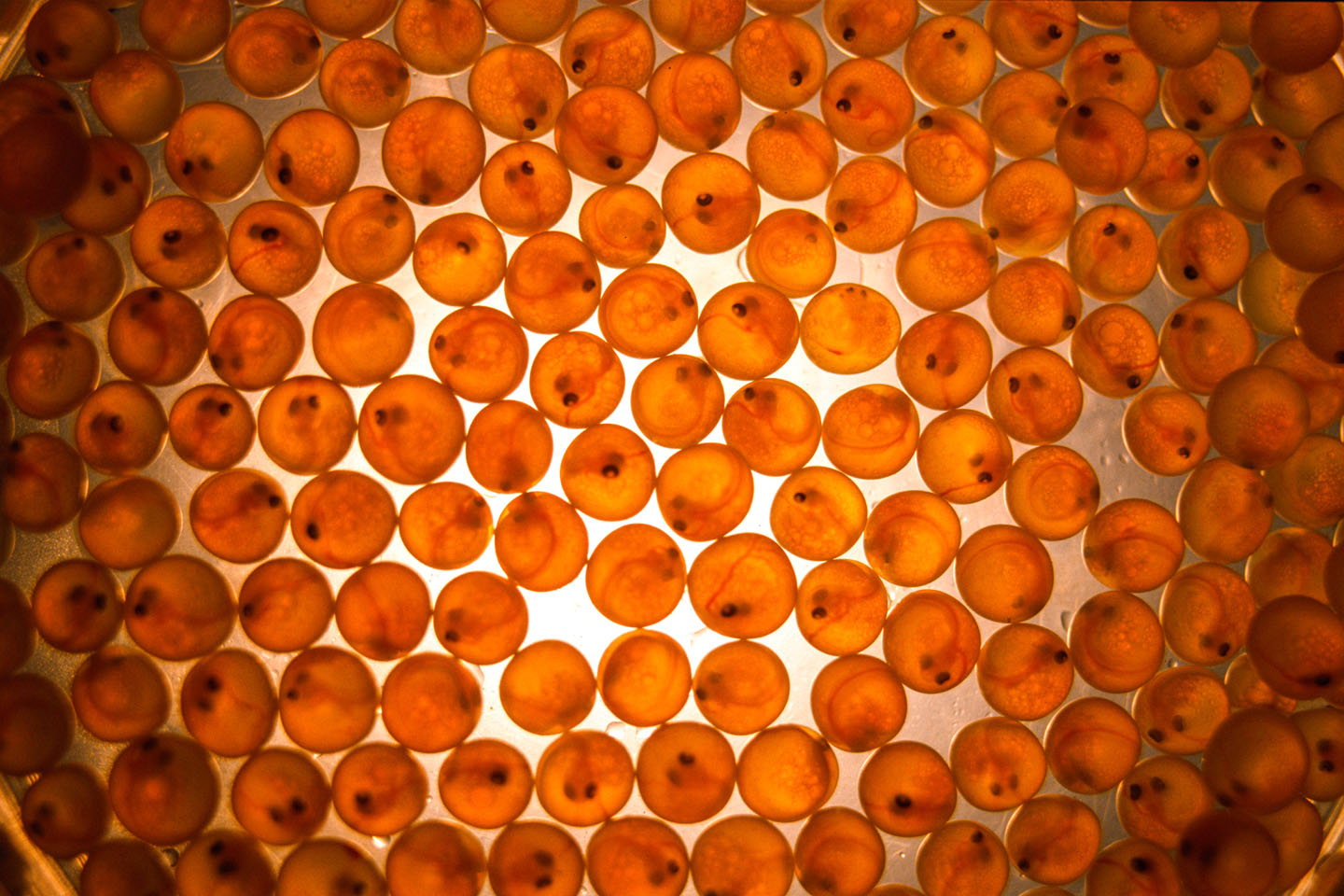

Once a female’s eggs are stripped, a male’s milt is immediately put into the pan of eggs to fertilize them. This is a tedious task and must be done quickly as the eggs are full of pores and, once exposed to water and air, will begin closing rapidly. The milt must be obtained and enter the egg’s pores quickly to fertilize them. After being fertilized, the eggs are placed in a large container with running water for three to four hours to harden. Afterward, they are moved into the hatching troughs in the hatch house.

The already fertilized eggs that are delivered to the hatchery are shipped in ice water. Before these eggs can be placed in hatching troughs, the eggs are tempered by slowly warming the water they are in for three or four hours to match the temperature of the water in the troughs.

Once in the troughs, temperatures have to be regulated as warm water speeds up the hatching process, which produces weaker fish and could lead to death. Successful temperatures are between 50 and 60 degrees for trout, and the spring-fed water from Rock Creek is about 56 degrees year-round.

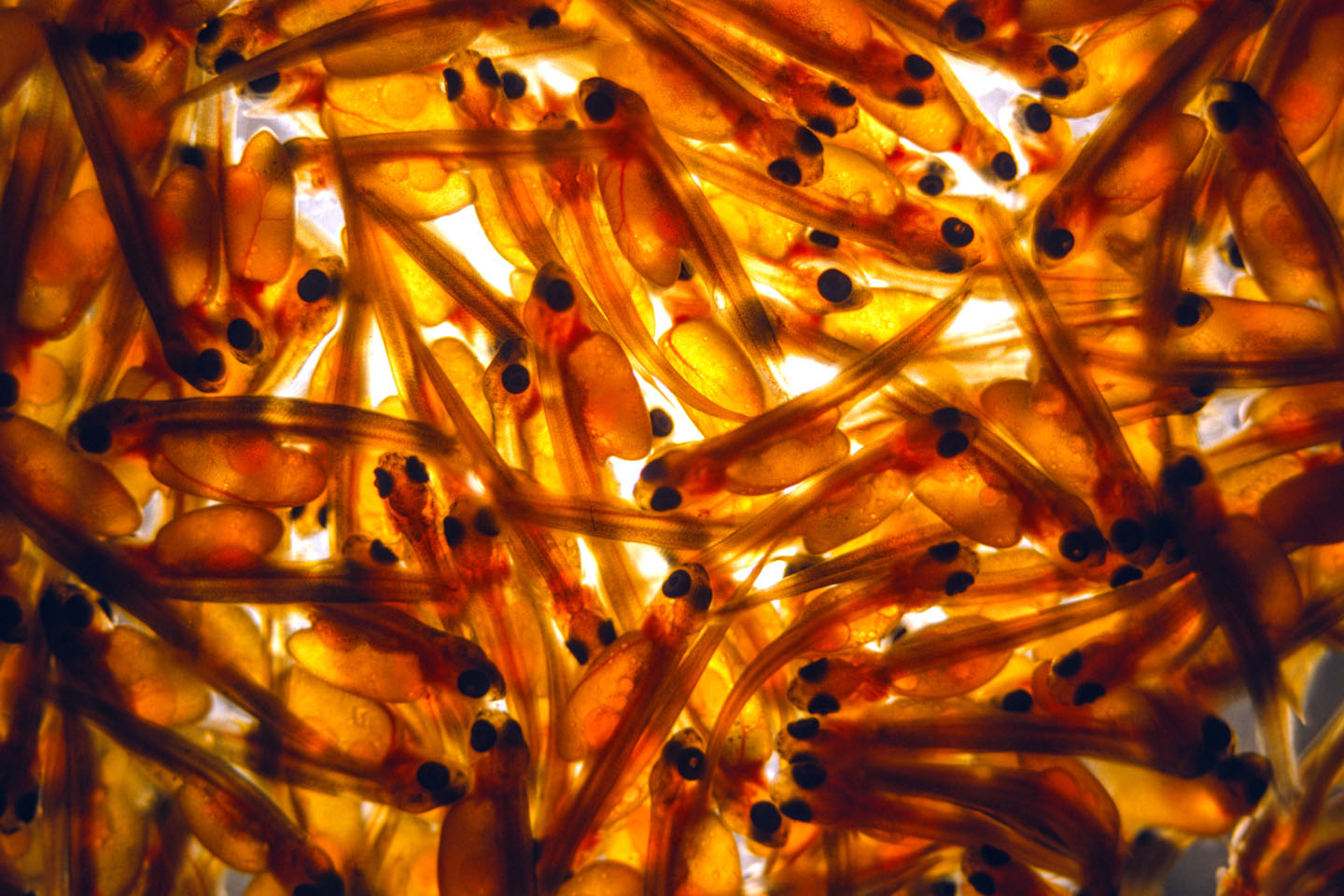

Newly hatched trout absorb their yolk sac as food, and once the sac is gone — around 14 days — trout look for other food swimming toward the surface of the water. Because of this, staff feed them ground liver four or five times daily.

As the fry grow, they are thinned out to make room for slower-growing trout. Once trout reached a fingerling size of 1 to 2 inches, they are transferred to outdoor circular ponds. At this point, food is changed from a liver diet to a liver-cereal mix. The cereal is prepared by feed mills and is high in protein and vitamins.

As the trout grow, they are again sorted with the larger fish placed in spring-fed ponds while smaller trout are held in the circular ponds. The sorting process is repeated until the fish are at a desirable length for pond stocking.

Once in the pond, trout are fed only twice per day for two weeks before feeding is cut to once a day. Trout also feed on insect life naturally produced in the ponds. Surface feeding for insects prepares the trout for introduction into rivers, streams and lakes where they must feed on their own for survival.