Story by Lauren Salick

Photos by Alex Wiles

Like a trusty, utilitarian pair of cargo shorts, the “accessories” genetics gifted to wild animals not only provide style but also varying adaptations for survival. Animals use their functional body adornments to protect themselves from predators, acquire food, navigate their environment, thermoregulate and even attract mates. While cargo shorts aren’t exactly the human ideal of “sexy,” many species use functional fashion to display messaging of strong genetics and lineage to prospective partners. Animal “fashion” is the perfect intersection of function. And many of these adaptations exist at the microscopic level.

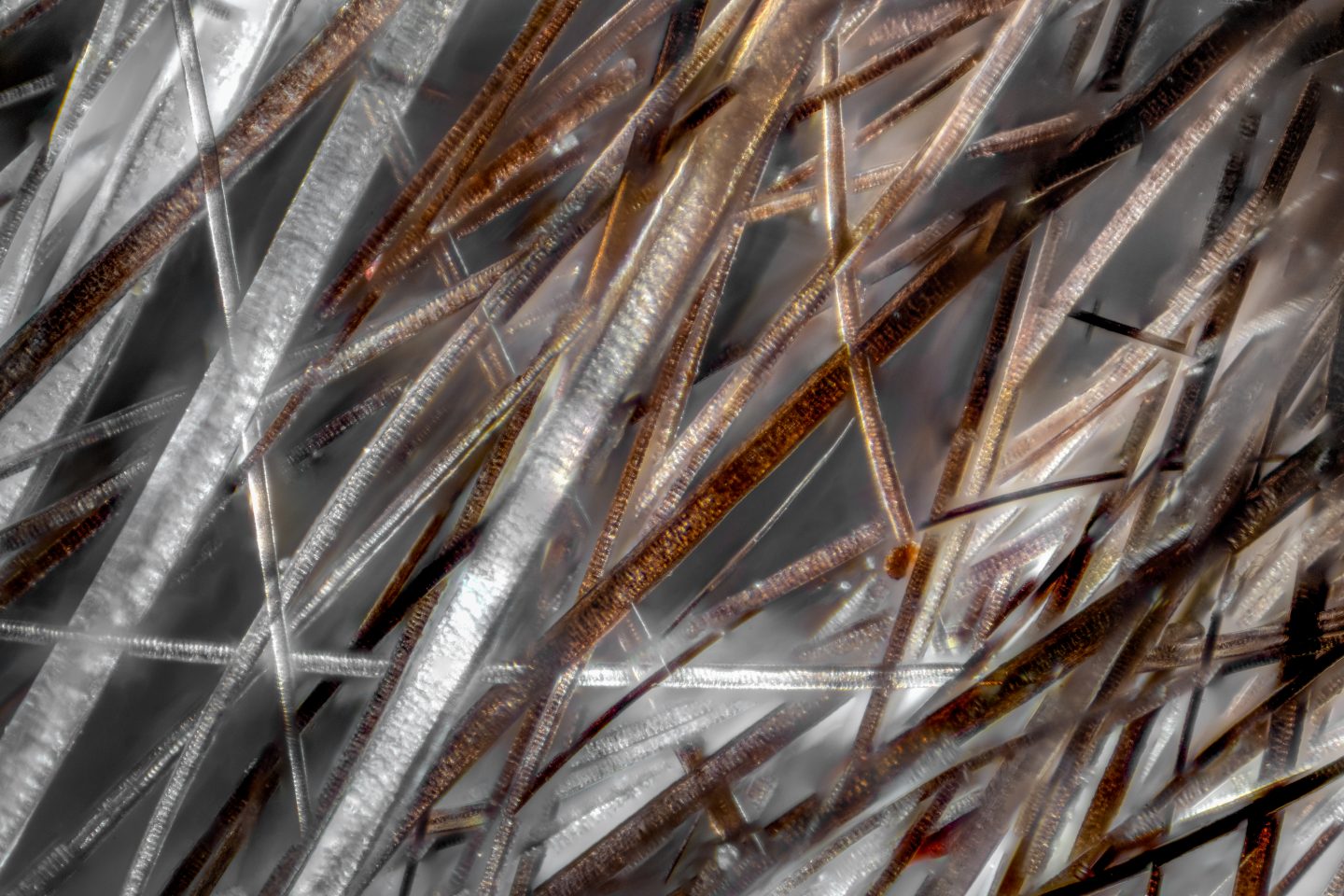

Feathers

Whether pokey or soft, colorful or camouflaged, feathers generally come in seven unique “styles” — wing, down, tail, contour, semiplume, filoplume and bristle. Each type of feather supports the bird in unique ways. Stemming from a firm, yet supple central pillar called the rachis are thin filaments called barbs, which branch further into barbules. Zoomed in, these teeny-tiny barbules possess interlocking structures that hold the barbs “zipped” together, creating tension to ensure a smooth surface for air or water to glide across — such as on a “wing” feather.

Yet some feathers are less uniform: Down feather barbs billow in chaotic fashion, trapping warm air closer to the body of the animal. A bristle feather, by contrast, sports a few barbed filaments at the beginning, and then a towering, naked rachis. These hair-like feathers are often found around a bird’s eyes and beak, offering contextual sensory information to the animal in whisker-like fashion.

While some feathers sprout from the bird’s skin, others, such as the primary wing feathers, will actually grow out of, and be attached to, the bird’s wing bones. These stout feathers are filled with pulp as they grow. When the pulp recedes back into the bone, it leaves the hollow, quill-like feather, long used by humans as writing instruments.

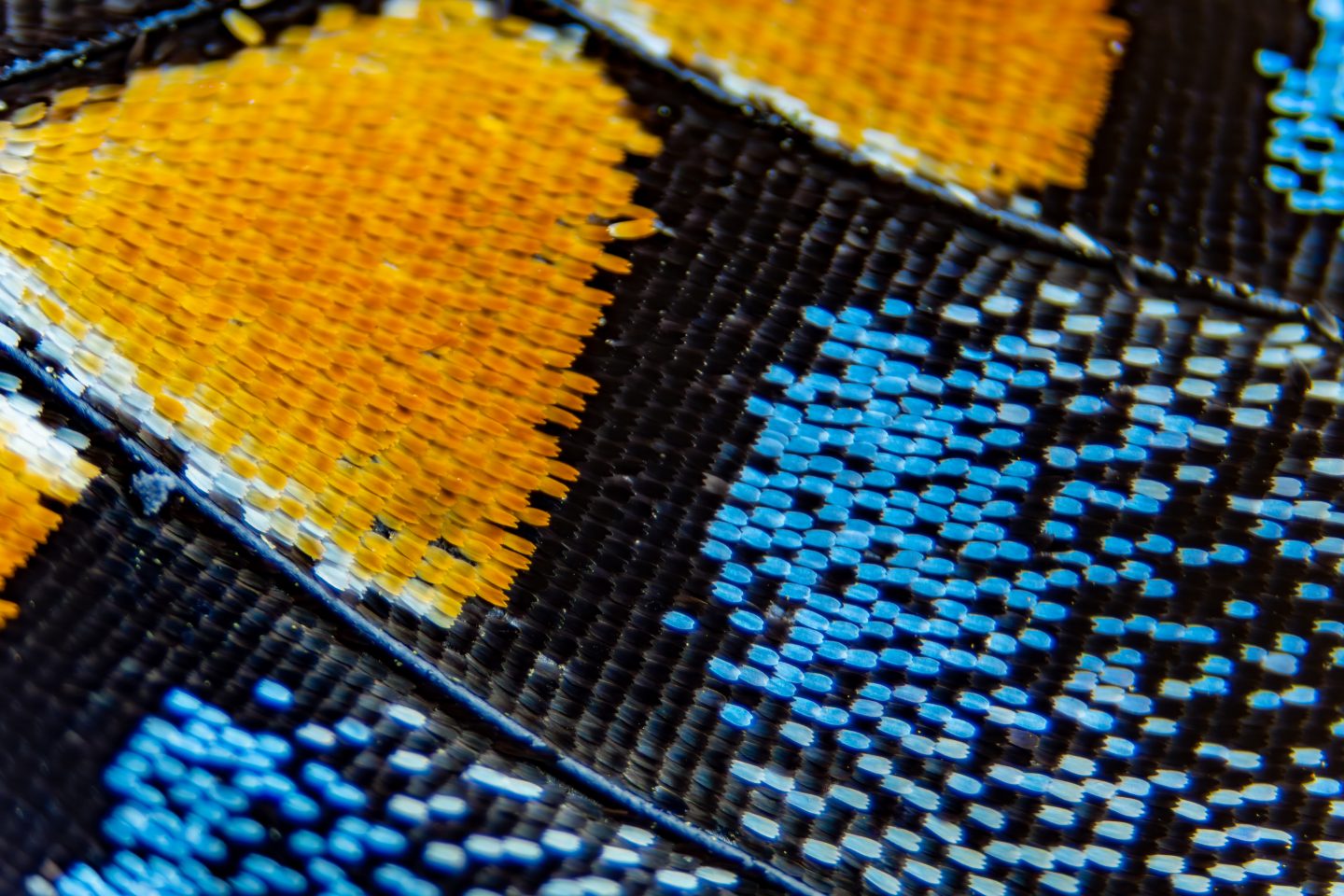

Wing Scales

Lepidoptera, the taxonomic order that makes up butterflies and moths, means “scale wings” in Latin. While the surfaces of butterflies and moths’ wings look smooth and uninterrupted to the human eye, it is actually adorned in thousands of colored, microscopic scales. The entire wing is also veined with delicate, air-filled structures that provide support and strength. When we take a closer look, these delicate structures are easily rubbed off and give these winged insects their brilliant colors and patterns. Anyone who has caught a butterfly and come away with fine, dust-like particles on their hands has experienced this personally.

Physically, the scales are made of overlapping pieces of chitin — a strong natural biopolymer — layered on top of two thin membranes that create the wing, fed by even smaller veins. Together, they make brilliant patterns of spots, stripes, swirls and colorful blocking — making some wings real runway showstoppers and others, more demure and camouflaged.

But scales are not just a flashy accessory. These shingle-like structures can also help the insect stay warm. On sunny days, you might see a butterfly basking with its wings open, its darker pigmented wing scales soaking up the solar radiation.

Other types of specialized scales possessed by some male butterflies called androconia release provocative pheromones for breeding. Some scales affect air flow, reducing drag, as the insect flies aiding in its aerodynamic abilities. Some species’ scales are even hydrophobic — capable of shedding water and dirt.

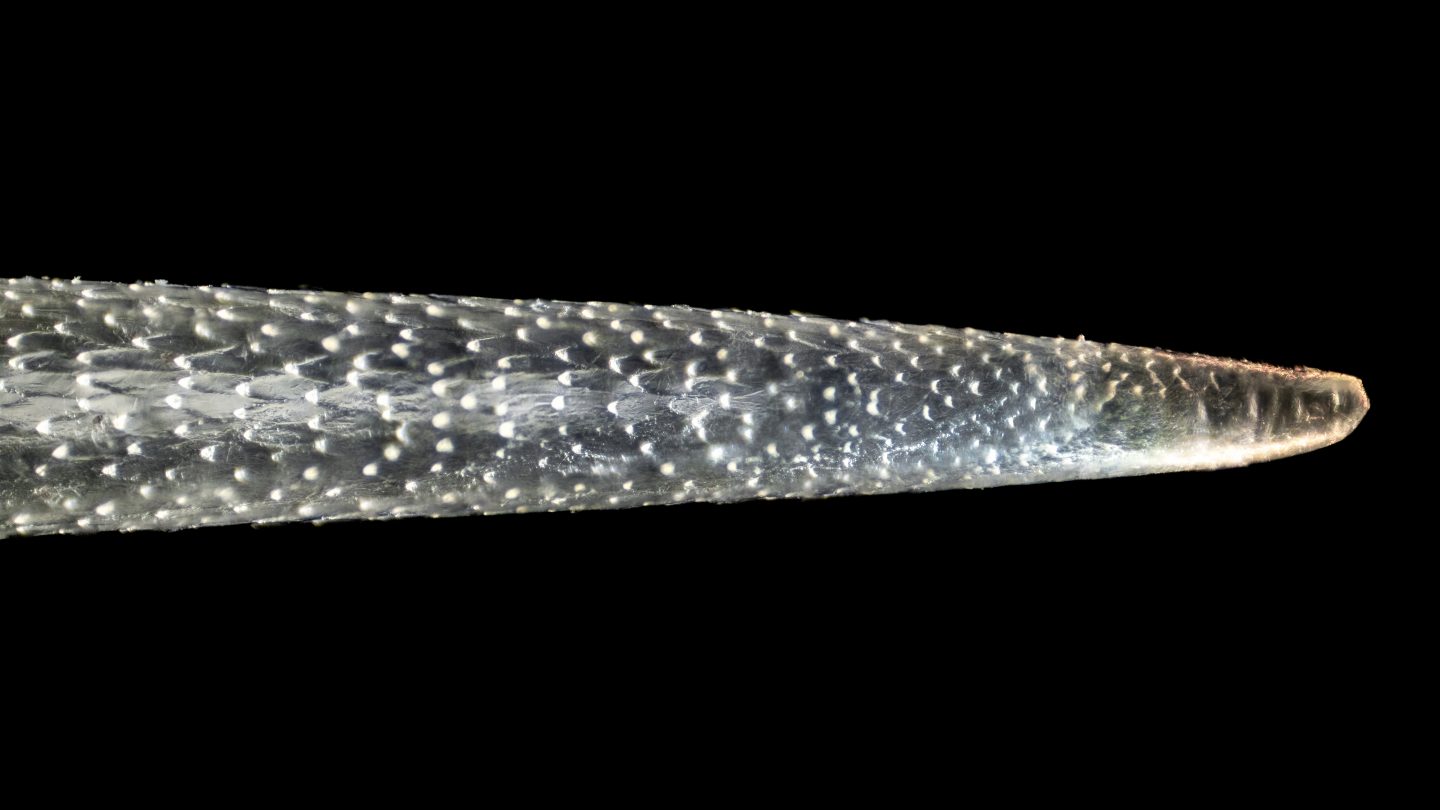

Quills

Quills are a type of modified hair armor-plated in sheaths of keratin. While they’re not “shot” from the animal like urban legend might claim, quills do often possess irritating backward-facing barbules near the tip that ensure difficult removal from the skin of a would-be predator. Nebraska’s sole quill-wearer, the North American porcupine, has quills approximately the diameter of an 18-gauge hypodermic needle, but only requires half the amount of force to break the skin barrier than said needle.

A fine protective coat, animals also use quills to send a message of warning. This is known as aposematism, or deterring predators with color or body coverings. Flaring them wide or rattling them together, a porcupine can deter an animal it deems a threat in an intimidating display. Often, the quills used in this acoustic form of aposematism are hollow for enhanced noise-making, such as those on African species of porcupines.

It’s important to note that quills are different from another pokey accessory — spines. Quills are a type of spine that fall out easily and have different shapes and lengths depending on where they are located on the body. “Spine” is a generalized term for any hardened, keratinized modified hair, encompassing even those that are deeply embedded into an animal body — such as with the hedgehog. Both of these spines evolved separately in different species and are thus an example of convergent evolution.

Convergent evolution happens when animals that are not closely related, such as porcupines and hedgehogs, or do not share a common ancestor, adopt similar features or characteristics on their bodies to meet a similar need — in this case, for protection.

But could this “fashion” be fatal? Porcupines climb trees, and as they are not the most agile of animals, often subsequently fall out of them. Dislodged quills can embed themselves into the porcupine’s skin in a luckless condition known as “self-quilling.” It turns out these reclusive rodents have a plan for that, too — studies have shown that North American porcupine quills are covered with free fatty acids, providing antibacterial properties that prevent infection from self-inflicted stabs.

Functional Fashion — Always in Season

Like humans and clothing, animal body coverings are a genetic response to their ecology and habitat. Carefully curated over generations, feathers, fur, scales and quills represent the dominating phenotype that is most successful for survival. If a fish’s scales are the “cargo shorts,” then a phenotype is the outfit — or a set of observable characteristics, including the fins, gills, coloration and other adornments on an animal’s body. While one species may have varying phenotypes, there is generally one that is predominant — and this “trending” outfit became popular not via the runway, but by fitness in an animal’s environment.

While fanciful feathers, embellished scales and rattling quills may seem analogous to the fripperies of haute couture — when we take a closer look, animal fashion serves much more than just for show. Exciting discoveries and inventions inspired by animal body coverings are sure to continue in our future.

Lauren Salick is the education director for Nebraska Wildlife Rehab, dedicating her career to fostering respect and harmony between humans and wildlife. Alex Wiles is the creative director of NEW Multimedia.