By Justin Haag

Coursing through cattle country, the name might conjure up a dusty trail to drive longhorns across the prairie. But the Cowboy Trail — formally the Cowboy Recreation and Nature Trail — instead caters to the drive of cyclists, runners, hikers and, yes, even some horseback riders, as it crosses some of Nebraska’s most scenic regions.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the trail, which was born when trains stopped running on tracks operated by the Chicago and North Western Railway. The historic route known as “the Cowboy Line” was developed in the 1880s and played a critical role in Euro-American settlement and commerce in northern Nebraska.

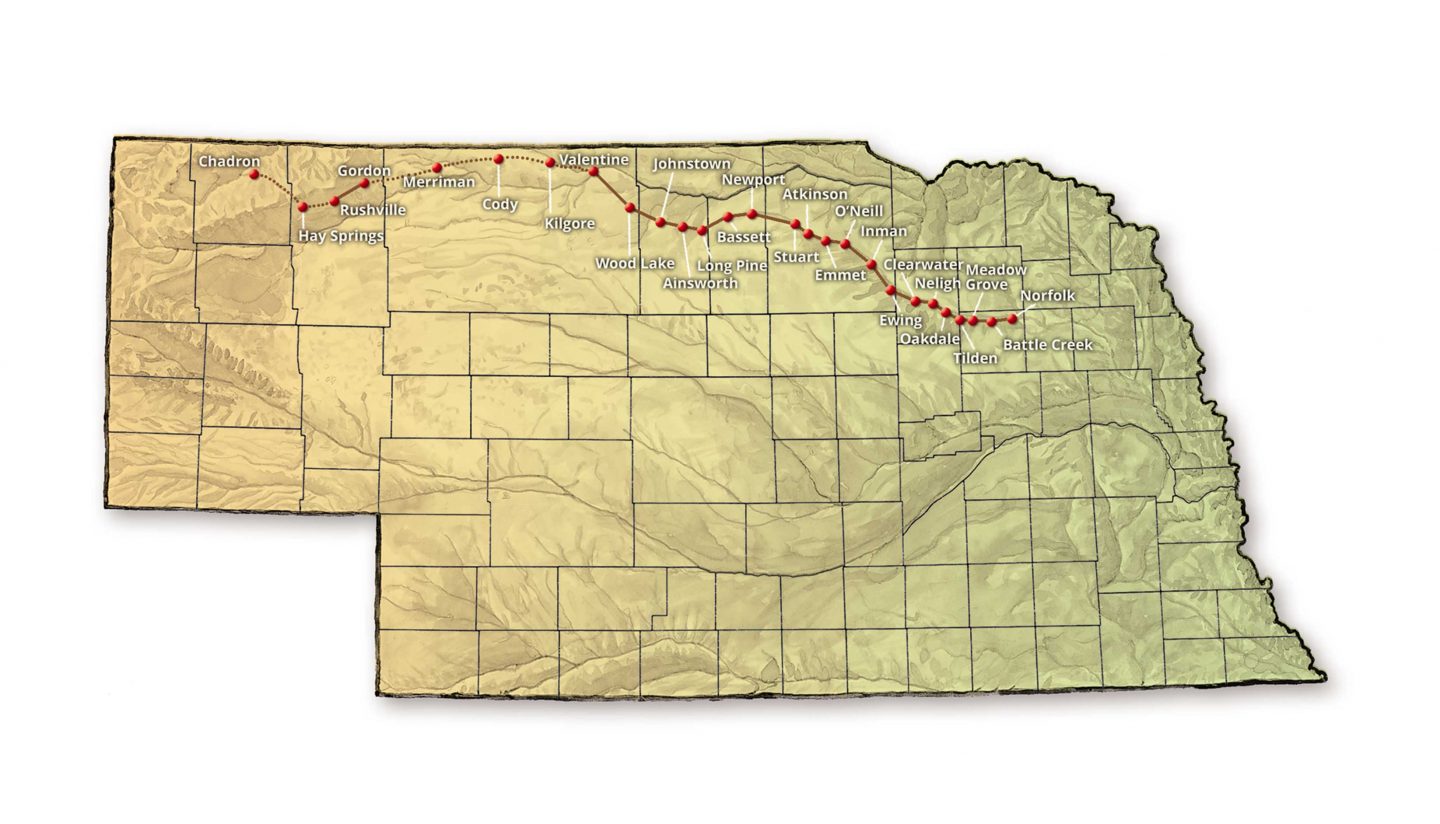

When economic shifts forced the railroad company to cease operations on the line in the 1980s, trail enthusiasts capitalized on an opportunity. The Rails-to-Trails Conservancy, a national organization based in Washington, D.C., purchased the right-of-way between Norfolk and Merriman for $6.2 million in 1994 and gifted it to the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. The portion between Merriman and a spot a few miles east of Chadron was added in the early 2000s when operations ceased there. In all, there are 317 miles.

At the time it was purchased, the trail was publicized to be the longest rails-to-trails conversion in the country. So far, 187 miles between Norfolk and Valentine have been completed, along with 15 miles between Gordon and Rushville. Work is underway to complete more.

Yes, development has been derailed along the way, but progress continues, and like the Little Engine That Could, proponents are building momentum with an I-think-I-can attitude.

Big Features for a Big Trail

The Cowboy Trail is among the many rail-trails throughout the nation that have capitalized on the gentle grade, 2 percent or less, and wide curves of old rail lines. Federal law allows trail development of the lines through rail-banking, a provision that preserves railway corridors should they ever be needed for trains again, but allows recreational use in the meantime. About 25,000 miles of rail-trails have been completed in the United States, with nearly 9,000 more in progress.

With the dirt work and sturdy bridge structures already in place, old rail lines make ideal multi-use trails. Once the steel, ties and ballast are removed, the trail is surfaced with low-maintenance crushed limestone, and bridges are fitted with wood decking and safety rails.

Alex Duryea, recreational trails manager for Game and Parks, said the Cowboy Trail has become a special way for people to experience a large portion of the state.

“And, best of all, it’s free to do it,” he said. “Just hop on and go.”

The Cowboy Trail, albeit desolate in places, features some of the best aesthetics Nebraska has to offer. Beginning with its trailhead at Ta-Ha-Zouka Park in Norfolk, it takes people through the lush farmland of the Elkhorn Valley. Farther west, it crosses the pristine trout waters of Long Pine Creek, patches of wetlands and expansive grassland in the northern Sandhills, and overlooks the mighty Niobrara River. Those who travel the full distance get a sampling of at least five of the state’s specified Biologically Unique Landscapes while going through more than 25 cities and villages along the way.

Much of the trail runs parallel to U.S. highways 275 and 20, the latter designated the Bridges to Buttes Scenic Byway. That name provides a clue to some of the trail’s most impressive features.

More than 200 bridges on the trail have been converted for recreational use. Southeast of Valentine, the bridge over the Niobrara River is a quarter-mile long and 148 feet high. Farther east, the 145-foot-tall bridge over Long Pine Creek spans 595 feet.

Also attractive are the old rail line’s series of ornate arched culverts constructed of stone blocks. Perhaps the most impressive, just west of Johnstown, is 32 feet wide and 232 feet long. Plum Creek flows through it.

Part of the trail’s allure is the same thing that’s credited for slowing development: the sparse population along the route.

Food, lodging, gear and other amenities can be found in the route’s largest cities — Norfolk, Valentine, Ainsworth and O’Neill. North Fork Outfitting in Norfolk caters to cyclists with a shuttle and other services, for instance.

Fun stops can be found in smaller locales. One such place is in Newport, population 97, where resident Melissa Denny renovated an old hay scale building to a pool hall. The unmanned facility is always open for trail users to shoot a game of pool. Drinks, snacks, shirts and hats are available on the honor system.

Other popular sites along the way are the Neligh Mill State Historic Site and a pair of restored depots — one made of brick in O’Neill and another constructed of wood at Long Pine.

The trail is surely not as busy as those in and near metropolitan areas, but Duryea said it gets a lot more use than most people think.

“We have automated trail counters out there now, and just from January through the end of July 2024, we had 87,000 counts. That’s just between Norfolk and Valentine and doesn’t include the section between Gordon and Rushville,” he said.

Most of the traffic occurs near communities along the way, but there are users who like the challenge of taking it on in its entirety.

Kylee Borg of Stuart, population 590, has a front row seat for activity on the Cowboy Trail from her convenience store, SouthSide Mini Mart.

“We see a lot of bicyclists stopping along their trip to fuel their bodies — they don’t need gas, but they need bananas, water and whatever else to make it to where they’re going,” Borg said. “I would have never imagined how many people bike the trail during the summer. A lot of Americans do it, but there are also so many people from overseas. This past summer, we had a lot of visitors from Europe.”

Borg helped promote the trail in fall 2024 by getting firsthand experience in one of its premier activities. Even though she doesn’t consider herself to be a runner, she was persuaded by fellow community members to enter the Cowboy 200, a grueling footrace that covers the trail’s entire distance between Norfolk and Valentine. She made it 36 miles before bowing out of the 100-mile category. This year’s race is set for Sept. 26.

Working Away

With little revenue to support the trail, Game and Parks has had challenges maintaining and developing it since the beginning, “We are statutorily mandated to develop, operate and maintain this corridor as a state recreational trail, so we are doing our best with what resources we have,” Duryea said.

With the trail’s position in the Elkhorn Valley, occasional high waters have caused problems. Flooding in 2010 washed out a large section of trail and several bridges east of Clearwater that have yet to be repaired due to funding and logistics, forcing a detour along Highway 275.

In 2019, flooding resulted in five Federal Emergency Management Area disaster sites along the trail. Three of these locations have been fixed with disaster funding. They include sites just west of Norfolk and Neligh, and another east of Long Pine.

Remaining is a spot between Neligh and Oakdale where floodwaters washed away the approaches to a bridge that still stands. The other location to be fixed is erosion around a twin 260-foot-long, 4-by-8-foot box culvert underneath about 80 feet of embankment east of Valentine.

“If you’re just walking along the trail, you’d have no idea that it’s even there,” Duryea said. “It’s a costly repair because it’s in a remote, hard-to-get-to location.”

The setbacks from flooding have slowed new development, but progress is being made.

An increased focus on maintenance has made the trail more enjoyable for users in recent years. It also has seen a boost in advocacy from its communities, with some stakeholders along the route forming the Cowboy Trail Coalition.

The Cowboy Trail got a boost in publicity in 2019 when the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy announced an effort to connect Washington D.C. with Washington’s Pacific Coast via what they dubbed the Great American Rail-Trail. With its central location, the Cowboy Trail is key to the effort which links 150 existing rail trails on the 3,700-mile-long route.

Kevin Belle, the conservancy’s project manager for the effort, said more than half of the trail is already in place and that it has already become popular even though numerous gaps exist along the way.

“The Cowboy Trail is a big part of our history. You all are pretty important with your location as the midpoint, and also because you’re one of the longest rails-to-trails conversions in the country. That helps make this trail possible,” he said. “Now our big job is to figure out how to fill in the remaining 1,600 miles, including the segment of the Cowboy Trail that still needs to be finished.”

Two nonprofit organizations in the Panhandle, Cowboy Trails West of Sheridan County and the Northwest Nebraska Trails Association based in Chadron, are working with Game and Parks and other stakeholders to develop the western end, which takes users from the edge of the Sandhills through another one of Nebraska’s most scenic places, the Pine Ridge.

Cowboy Trails West was born after cyclist Kris Ferguson of Gordon was injured from being struck by a vehicle while pedaling on the highway’s shoulder. The cyclist gathered with other persistent Sheridan County residents to advocate for completion of the trail, eventually partnering with Game and Parks to complete the portion between Gordon and Rushville in 2015.

Contractors for Game and Parks decked bridges through the Pine Ridge between Rushville and the terminus east of Chadron in 2024. That section is projected to receive surfacing in 2026. The trails association in Chadron is working to develop a trail alongside the still active rail line for the last 5 miles leading to its downtown area.

Once the section between Rushville and Chadron is complete, a 91-mile gap between Valentine and Gordon will remain. It is the trail’s most sparsely populated section, but proponents believe its Sandhills scenery has potential to attract interest from afar.

“I’m sure we could get money to develop the entire trail now,” Duryea said, “but doing so without having maintenance dollars would be setting us up for sure failure. The big key is getting maintenance dollars. We don’t even have enough money to maintain what we have. We need to get a little more money to spur development and maintain the additional miles out west.”

As with trails throughout Nebraska and the nation, much of the funding for development has come from the Federal Highway Administration’s Recreational Trails Program and Transportation Alternatives Program.

Game and Parks is exploring other revenue sources, such as building a fund to serve as principal for a lasting endowment. Other ideas have been explored. Bills introduced to the Nebraska Legislature in 1997, for instance, would have provided about $1.5 million of annual funding by taxing bicycle sales and raising vehicle registration fees, but they failed to pass. Also considered have been voluntary fees at iron rangers, but Game and Parks has been hesitant to this idea, projecting the cost of management would exceed income.

Wherever the money may come from, Duryea believes it’s a good investment.

“The trail is so much more than just a trail,” he said, noting the corridor contains 5,000 acres of opportunity for wildlife and its habitat. Along the way, Game and Parks also facilitates hundreds of crossings for electricity, fiber-optic cable and pipes for water and sewer.

One full-time and two part-time employees are assigned to the trail now. Game and Parks is working to secure funding for another staff position to maintain the west end.

Duryea is optimistic for the trail’s future.

“I’m not saying we’re going to complete the entire trail in five years or anything, but we have some good momentum, and it will surely be a nice thing to see when it happens,” he said.

Development of the entire route could also give Nebraska a point of pride for being the longest rails-to-trails conversion in the country, as it was first advertised to be. The 240-mile long Katy Trail in Missouri claims to be the nation’s longest developed section, but proponents want the Cowboy to someday lasso that claim.

By staying the course and chugging along — or, perhaps, cowboying up — proponents are betting on it.

Tackling the Trail

The Cowboy Recreation and Nature Trail is open to hiking, running, cycling and other non-motorized travel. Horses are allowed alongside the trail, too.

Mountain bikes with large tires, such as fat bikes and 29ers, are recommended. Especially late in summer, the burs of puncturevine (shown above), or “goatheads,” are present in many places, so riders should be equipped with extra tubes with internal sealant and an air pump.

Class 1, 2 and 3 eBikes — pedal-assisted with a top speed of 28 mph — are permitted.

Visit OutdoorNebraska.gov for information about the trail, including a list of events planned for its anniversary.

The Cowboy Trail’s Railroad History

By David L. Bristow, Nebraska State Historical Society

Today’s Cowboy Trail follows an old railroad that was organized in January 1869, less than two years after Nebraska statehood. Its founders called it the Fremont, Elkhorn & Missouri Valley Railroad. Starting in Fremont, track-laying crews followed the Elkhorn River to Wisner before an economic depression halted construction in the early 1870s.

According to David Seidel’s book, Fremont, Elkhorn & Missouri Valley R.R. Co., the original plan was to continue northwest to the junction of the Niobrara and Missouri rivers. The idea was to connect with steamboat traffic on the upper Missouri. Plans changed after gold was discovered in the Black Hills. The army fought the Great Sioux War to force the Lakotas to sell the Black Hills. Afterward, the railroad began building again, but with a new destination in mind. Following the Elkhorn upstream, the tracks reached Norfolk, Neligh and then O’Neill by 1880.

As the railroad approached the headwaters of the Elkhorn, Chief Engineer J. E. Ainsworth planned a route west across the Sandhills. The rails reached Long Pine in 1881 and Valentine two years later. The route originally looped south at Long Pine to avoid a deep canyon, but there was no avoiding the Niobrara River, which had to be spanned with a high bridge. The original wooden structure was replaced in 1910 with a steel bridge that is still enjoyed by Cowboy Trail travelers today.

The Chicago and North Western Railroad took over the Elkhorn route in 1882 and soon found itself in an enviable position. A competitor’s planned route to the Black Hills was blocked when Congress banned railroad construction on Indian lands in Dakota Territory. The C&NW soon boasted of having “The Only Line between CHICAGO and the BLACK HILLS.” The rails reached Chadron in 1885, Rapid City in 1886 and Deadwood in 1890. The railroad also continued west from Chadron into Wyoming.

The Elkhorn route carried freight and passengers for many years. Eventually traffic declined, and operations ceased on most of the track in the 1980s and 1990s.

Visit NSHS’s website at history.nebraska.gov.