Story and photos by Eric Fowler

There is a lot of screaming in downtown Norfolk these days, especially on a hot summer day. Some are screams of fear, but most are joy from children and a fair share of adults. You hear them nearly every time someone goes over one of the seven drop structures on the North Fork Whitewater Park on an innertube or kayak.

You might also occasionally hear someone say: “Surf’s up, dude.”

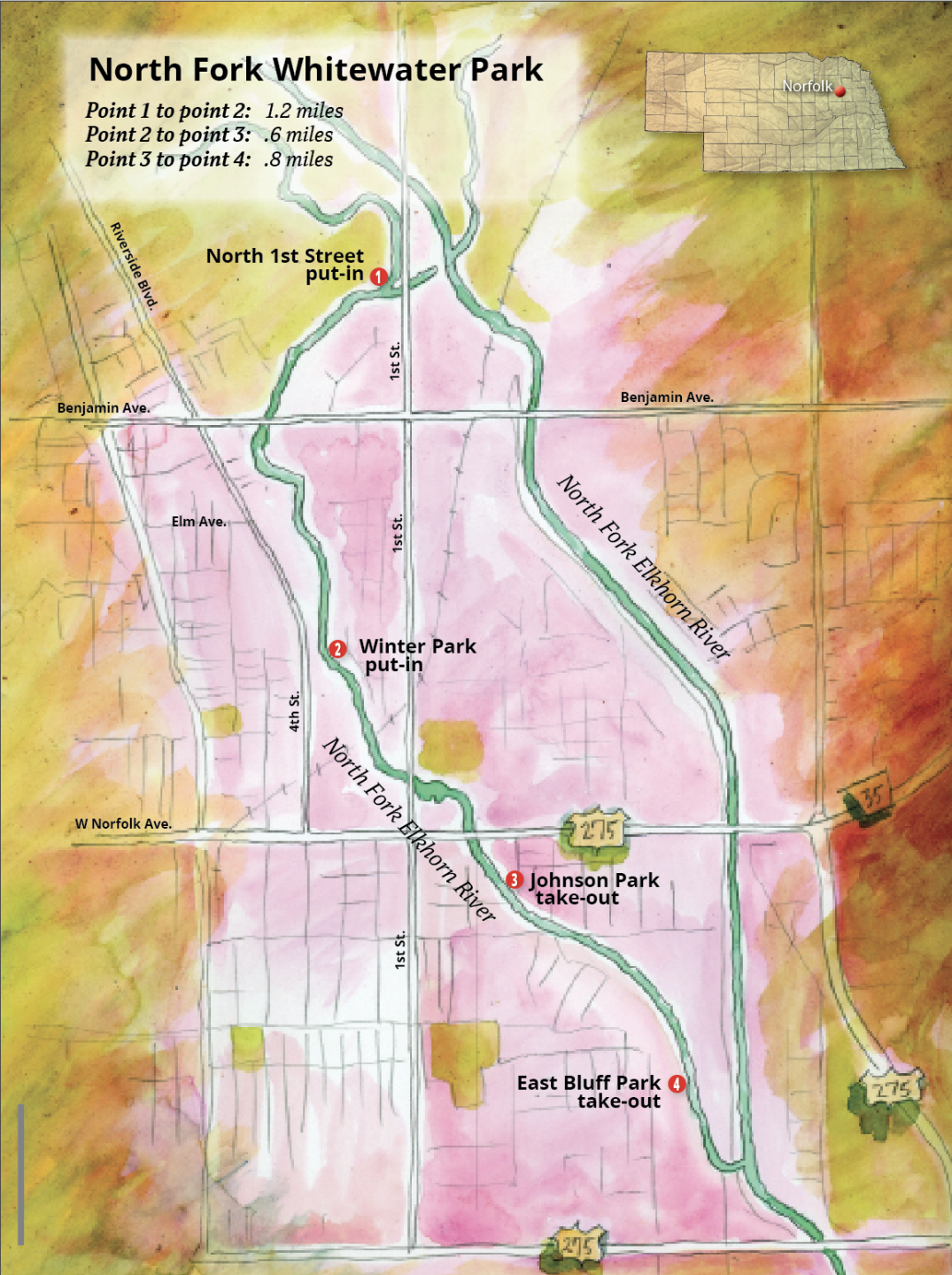

The water park, which opened last June, grew from an effort to revitalize the North Fork of the Elkhorn River and the riverfront around it, including the historic Johnson Park. The end result includes the whitewater park and its unique surf wave, a 2.6-mile-long water trail that stretches across the city.

The number of people who floated the river and braved the new rapids during the park’s first summer of operation, even before the finishing touches were done, was more than most could have imagined.

A River Reimagined

One of the first endeavors of the settlers who arrived in what is now Norfolk in 1866 was to build the Sugar City Cereal Mills. A dam was built on the North Fork north of what is now 1st Street and Norfolk Avenue to power the grist and sawmill. The pool below the mill dam became a swimming hole where people cooled off in the summer. In 1937, during the Great Depression, a Works Progress Administration crew built Johnson Park below the dam. The park and its ornate gardens, however, were no match for the power of the river and the 17 floods that occurred between its construction and 1962.

That year, following a spring flood that sent water spilling over 90 city blocks, local officials and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers finalized plans to build a 4.5-mile-long canal to carry floodwaters around the east side of the city.

The river still flowed through town, with water levels controlled by gates where it branched off from the flood channel. But it was neglected and, for the most part, forgotten, so much so that Nebraska Avenue was built through Johnson Park, separating it from the river. The mill dam, which had also been producing hydropower before it closed, remained as an obstacle.

“The entire area was unsafe for recreation, and it was kind of an unsightly mess,” Josh Moenning, who served four years on the Norfolk City Council and eight as mayor before stepping down in 2024, said of the river flowing through downtown. “You would see, on occasion, people fishing down there, but certainly nobody was in the water.”

Efforts to revive the river began in 1974, when the Lower Elkhorn Natural Resources District and the city discussed removing the dam and creating a linear park along the North Fork. Other efforts followed, but they remained ideas until local leaders formed a Riverfront Development Group in 2008 and began focusing on creating a River Walk.

Tony Stuthman also had ideas for improving the river after paddling a canoe down it with a friend in 2013. “As I floated, I wondered why in the heck nobody was using the river for anything,” Stuthman said. “It was beautiful, and it was neat that it felt like you were in a different place. It didn’t feel like you were in Norfolk, or in a downtown area.”

He spoke with someone working on a housing development along the North Fork on 1st Street on the north edge of town about creating a put-in for float trips. The developer donated the land to the city, which developed a put-in and parking area there. The city also built a take-out above the old mill dam and in 2014, Stuthman and his wife started outfitting kayak and tubing trips on the North Fork and on the Elkhorn River southwest of town.

“The first three years, it was relatively difficult to even convince people to float [the North Fork] because they considered it a drainage ditch,” Stuthman said. “Once I got them convinced, then it was plain. It wasn’t the excitement of Niobrara.” And the 1.5-mile trip was short, taking an hour in a kayak, 90 minutes on a tube. Stuthman hoped the dam could be removed and the trips extended.

A few years later, when talk of a whitewater park surfaced, Suthman and a friend floated over the old dam on innertubes and sent a video to Riverwise Engineering, a Colorado company specializing in building whitewater parks around the country. They asked, “What could we do with this?” Riverwise said the dam, while an obstacle, provided opportunity: The 12-foot drop below it could be spread across eight shorter drops that could create whitewater features. Riverwise also said the North Fork had two more features a whitewater park needed: sufficient river flows for most of the year and — being a block from downtown — the proximity to people who will use it.

Revitalization Realized

With city and other leaders sold on the idea, the Lower Elkhorn NRD contributed $1 million to get the project started. Private donations and grants covered the rest of the $3.8-million cost of removing the mill dam and building the whitewater park. Limestone slabs salvaged from a historic building at the Norfolk Regional Center were used to build the water features, line some of the banks and for landscaping and walking paths to the river.

It was all part of a $17-million project that included a new vehicle bridge across the river on 1st Street and the removal of the portion of East Nebraska Avenue that separated Johnson Park from the river. The park also was renovated and now boasts a community festival space and amphitheater that can host concerts, markets and other events during the summer, and in the winter, an ice-skating rink. A multi-use trail follows the river, passing beneath the 1st Street bridge and two pedestrian bridges cross it, providing spectators a birds-eye view of the action on the whitewater features below.

And with the dam removed, the water trail now stretches from the north to the south end of town. At the start of the trail, the North Fork flows beneath the branches of trees overhanging the river, opening up after it passes beneath Benjamin Avenue. After flowing past ball fields and businesses, through a few backyards and Winter Park (where another put-in was built) it crosses the first point in the whitewater park, a 3-foot drop structure that creates a wave people can ride on surf boards or kayaks, a feature few parks of this type have. Six more drop structures dot the next third of a mile.

Most of the whitewater park is in Johnson Park, where the North Fork spreads out into a wide, shallow pond with a lush lawn on the north side and a beach on the south. On either, parents can sit back and watch their children splash in the water. Below the last feature, just past East Norfolk Avenue, floaters can haul their gear up a rock access to the parking lot and call it a day, or grab their tubes and walk the hike-bike trail back to the top and do it all again.

They can also continue floating the North Fork for nearly another mile to the final take-out point off Bluff Avenue on the southeastern corner of town.

Gates on the flood channel direct flows into the North Fork’s original channel, allowing the city to keep flows at the optimum level for the whitewater park, as long as there is enough flow in the river. Excess flows are sent down the flood channel.

If You Build It …

Officials estimated 30,000 people would use the river in a year. Stuthman said he thinks that number might have been reached in the first three months. He and his wife opened a surf shop steps from the North Fork and the surf wave. They rent kayaks, surf and boogie boards and tubes to folks who want to walk right down to the river and also offer shuttle service for those who want to float the entire trail.

Most people using the river outfit their own trips, bringing tubes or kayaks from home, but Stuthman said he is doing as much business in one weekend as he did in an entire year before the whitewater park opened. On one August weekend last summer, he said all he could see looking up and down the river near his shop were groups of tubers and kayakers. And in the park, the beach “was just wall-to-wall people.”

Those visitors came from throughout eastern Nebraska. But the whitewater kayaking and surfing culture is unique, and those who are into it will travel long distances to visit water parks that are popping up around the U.S., especially people who live in the Midwest, far from mountains. In its first year, people from at least 13 states visited the park, including some from both coasts.

“It’s an amazing addition for the state of Nebraska and the city of Norfolk,” said Brett Mjelde, a whitewater enthusiast from Council Bluffs, during his second visit to the park last September with his son and daughter.

While city leaders anticipated an increase in tourism from the water park, Moenning is equally pleased, if not more so, at the local interest, especially youths who flocked to the river during the heat of summer.

“A lot of times, these were kids whose families might not have been able to afford a pass to the water park. This was an opportunity for them to enjoy a natural resource in the middle of their community that’s easy to access. They can ride their bikes to it, and it’s free,” he said.

So if you find yourself in Norfolk this summer, don’t be surprised if you see kids, or adults, walking or biking across Norfolk with inner tubes or body boards slung over their back. Or if you hear screaming coming from the North Fork of the Elkhorn River. It’s all good fun. You might be wise to pack your swimsuit and join them.

What’d You Call It?

The North Fork of the Elkhorn River is what gave Norfolk its name. The city’s founders had submitted Nor’Fork, or some other variation of a contraction of the river’s name, to the post office, but somewhere down the line, postal officials thought it was a spelling error and changed it. Ask anyone who lives there, however, and many from Nebraska, and you won’t hear an “L” in the pronunciation.