By Renae Blum

Photos by Don Komarechka

Don Komarechka is a connoisseur of snowflakes.

Give him a random snowflake, and he’ll probably have a pretty good idea of how and why it likely formed, despite having no background in science. He can also tell you exactly how to take a macro photograph of that snowflake in dazzling detail, having photographed thousands.

Komarechka, a self-taught professional photographer from Barrie, Ontario, has made a career out of photographing what he calls “the unseen world,” including snowflakes. In his work, these small crystalline structures, which usually measure just a few millimeters in size, explode in astonishing detail, revealing intricate patterns and layers that glisten like small jewels.

It’s proof that you don’t need to look far for an amazing macro subject in the winter – just head outside during any given snowfall and take a closer look.

Komarechka stumbled onto snowflake photography almost by accident. “I bought myself an extreme close-up lens, and took it with me to work that day. You’d be surprised how interesting things around the office look at very high magnification – a typical ballpoint pen, a pushpin in a corkboard.”

Then it started snowing, and Komarechka kept shooting. Needing a darker background to make the snowflakes pop, he reached for a black mitten his grandmother had given him for Thanksgiving. It made all the difference.

“[The snowflakes] just sparkled. There was contrast and detail and shape and form, and it was magical. Every one of my snowflakes has been photographed on that same black mitten because it was just the perfect surface,” Komarechka said.

“That day when I went home from the office, I just kept shooting. And the bug had bit me at that point,” he continued. “It became – I don’t want to say an ‘obsession,’ but probably an addiction.”

Snowflake photography dominates Komarechka’s work from December to mid-March every year – the same subject, photographed and edited in almost exactly the same way, innumerable times.

“You’d think I would get bored with it after a while. But no, you always discover something new,” he said. “This past season I found many more exotic snowflakes than I would have expected.

“And when you see something that really breaks the norm, it’s a drug. It really does have something of an addictive quality.”

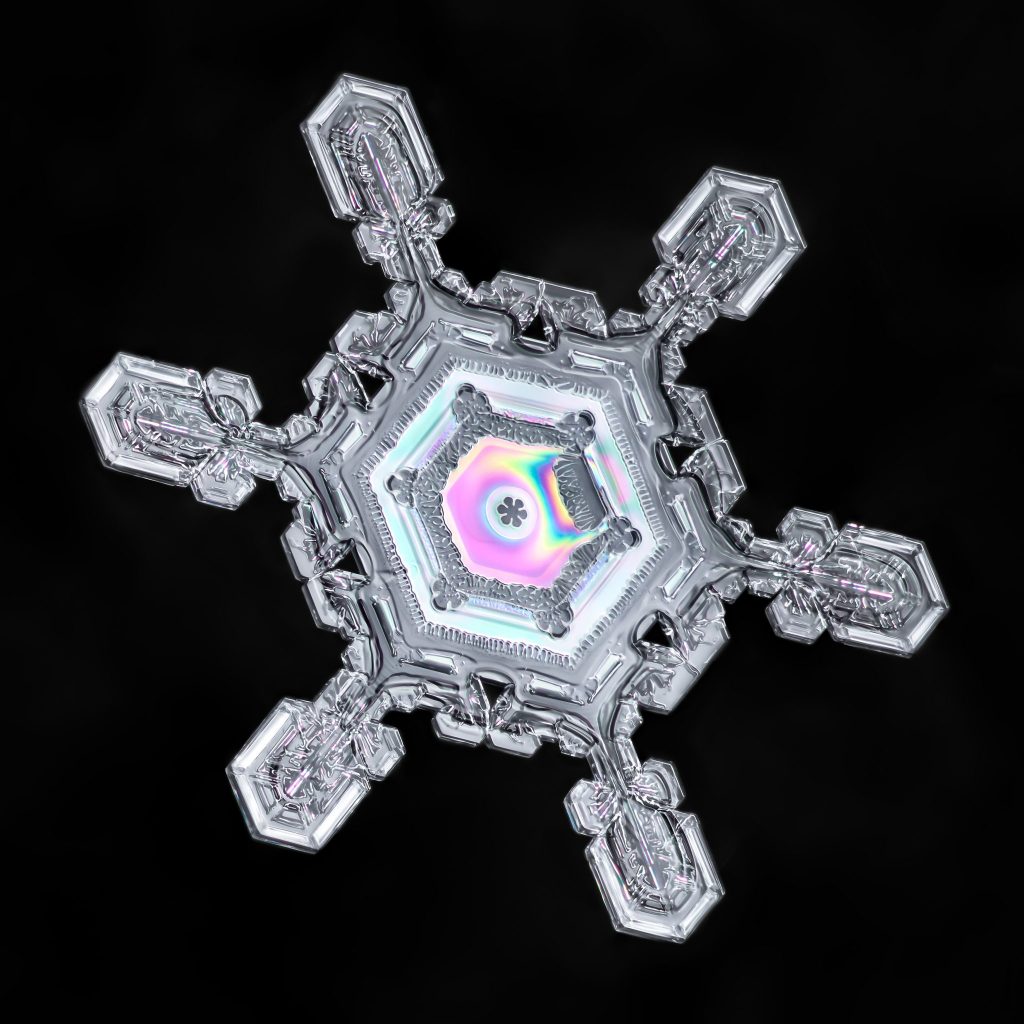

Komarechka’s way of photographing snowflakes is unusual. Most photographers shoot snowflakes on a plate of glass or another transparent surface, with light coming toward the camera from behind. Komarechka shoots snowflakes with light reflected off the snowflake from in front of it. Komarechka’s method is more work-intensive, but also makes it possible to see color in certain snowflakes – usually vibrant greens and magentas, but also blues, yellows and reds.

“This has to do with the same physics that puts rainbow colors in a soap bubble or an oil spot,” he said. “It can only be seen using reflected light. And because that hadn’t really been explored heavily in snowflake photography until I started doing it, it was a huge mystery to me as to where these colors were coming from. It felt good to kind of be discovering things like that.”

For Komarechka, it’s not only the beauty of snowflakes that’s appealing; it’s also the chance to research and truly understand his subject. Science never appealed to him in school, but “as soon as you give it a practical use, it becomes something entirely different,” he said.

o share all that he has learned, Komarechka wrote a 300-page book including the science behind snowflakes, as well as his process of shooting these composite images. While his method requires patience and time to learn, once you understand the technique, “it’s like riding a bike,” he said. “It becomes muscle memory.”

While Komarechka hoped to inspire others to take up snowflake photography with his book, he also anticipated most people would be interested in just looking at the coffee table photographs in the back. And that’s OK.

“Perhaps you will be inspired to put on your black mittens the next time it snows, grab a magnifying glass and see what you can find,” writes Kenneth G. Libbrecht in the book’s foreword. “Each snowfall provides a unique exhibit of frozen art, and the show deserves an audience.”

In Komarechka’s work, you’ll get a front-row seat.

To see more of Don Komarechka’s snowflake photography, see the print copy of Nebraskaland Magazine’s December 2018 issue.

Taking Snowflake Photographs – Don’s Method

To take his shots, Komarechka leaves a black woolen mitten and a paintbrush outside through the winter in an enclosed space, keeping them acclimated to the cold so the snowflakes don’t melt upon contact. He then lays the mitten flat and examines the snowflakes that collect. Often they are in clusters; Komarechka uses the paintbrush to carefully separate them and position a choice snowflake at a preferred angle. To make sure he can find the snowflake again when switching to his camera, he points the end of the paintbrush toward it, with the brush resting on the mitten.

Komarechka then takes a few test shots to find an angle that gives the snowflake a glowing, reflective surface. “And then I start out of focus on one side of the snowflake and start rapid-fire shooting, passing the camera through all the focus points that I need,” he said. “This will typically amount to a few hundred shots while the snowflake is still relatively unchanged.

“Once I’ve got these images, I’ll load them up into the computer, choose the puzzle pieces I need, and begin a four-hour process of getting a perfect image of all of them combined together in Photoshop.”

As far as equipment goes, Komarechka says any camera that can accept different lenses will work. You will also need a specialized macro lens, sometimes referred to as an “extreme macro lens,” that goes well beyond the normal 1:1 life-sized magnification. Komarechka also uses a ring flash for all his snowflake pictures. No tripod is needed.

While any snowfall can produce beautiful snowflakes, Komarechka says a temperature of about 14 degrees Fahrenheit is ideal. “So long as it’s below the freezing point by a couple of degrees, the exact same techniques work anywhere in the world,” he said. Low wind, low cloud ceilings, and snowfalls during the night are also promising conditions.

For a complete look at Komarechka’s method, pick up his book, Sky Crystals: Unraveling the Mysteries of Snowflakes, at skycrystals.ca.

Soap Bubble Magic

Snowflakes are not the only subject Komarechka photographs during the winter. Below, Komarechka explains his method for producing beautiful pictures of freezing soap bubbles.

“To create a freezing soap bubble image, at least the way I do it, start by lighting the bubble from behind with a bright LED flashlight. A Fresnel sheet magnifier can be used to refocus the light to be intensified over the bubble. To create the bubble, the formula is:

- 6 parts water

- 2 parts dish soap

- 1 part white corn syrup

The white corn syrup serves as a ‘cushion.’ When the bubble is blown from the end of a drinking straw, the syrup pools at the bottom of the bubble. When gently placed onto snow, this cushion prevents the bubble from popping instantly.

Temperatures between around -4 F and 17.6 F work best, with absolutely no wind. Even a little whisper of wind will knock the bubble about and it will pop/shatter.

Freezing soap bubble images are best taken when the bubble hasn’t yet completely frozen solid, so that you can see a variety of ‘puzzle pieces’ all about to connect together. You need to work fast, as most bubbles will freeze completely solid in around 10 seconds. There is a lot of trial and error involved, but once you get the hang of the technique you can start to use other foreground objects beyond just snow. I’ve used mineral samples, a branch from my Christmas tree, flowers and more. It’s a fun winter activity!”