By Eric Fowler

Nebraska has always had a proud hunting tradition, but by the 1970s, an increase in the number of incidents in the field was becoming a big concern. Some incidents had deadly consequences. Additionally, many hunters didn’t know the game laws or how to hunt ethically.

Many factors could have played into the increase. The state’s population was growing rapidly, and baby boomers were taking to the field. The population also was becoming increasingly urban, so more kids were growing up on playgrounds instead of hunting rabbits on the farm after learning how to safely use the .22-caliber rifle they got for Christmas. Most of the incidents involved young, inexperienced gun handlers.

Regardless of the cause, the need to teach people how to hunt safely was real. In 1974, the Nebraska Legislature recognized this need and passed a bill requiring youths ages 12 to 15 to pass a Hunter Safety course before they could hunt. The results have been what was hoped for and expected: The number of accidents began to decline, a trend that continues to this day.

The Need

The roots of Hunter Education stretch to 1949, when the National Rifle Association worked with the state of New York to develop the nation’s first Hunter Safety training program to address a problem: Many hunters knew little about firearms, hunting or how to hunt safely.

That program served as the basis for programs now taught and required, in some form, in every state. A few other states followed New York’s lead and launched Hunter Safety programs. Elsewhere, including in Nebraska, there were voluntary programs taught by NRA members, sportsmen’s clubs and 4-H groups.

In 1970, a major change was made to the 1937 Pittman-Robertson Act, which distributes federal excise taxes collected on firearms and ammunition to states for wildlife management and restoration work. Through the Dingell-Hart Act, a portion of a new excise tax on handguns could be used for Hunter Safety training programs, giving states the funding needed to hire staff to manage the programs, recruit and train volunteers and provide classroom materials.

“Without that funding source, we would have established a program, but would it be as robust as it is today? Probably not,” said Jeff Rawlinson, an assistant division administrator at Nebraska Game and Parks who oversees Hunter Education staff and has been involved in the International Hunter Education Association for many years. “Federal funding was crucial.”

The Nebraska Hunter Safety Program was launched by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission in September 1972. In the year prior, the agency had recruited and trained 200 volunteer instructors. The program, however, was voluntary.

When the Legislature passed its bill in 1974, Game and Parks immediately boosted its efforts to recruit and train instructors in every corner of the state, ensuring those required to take the class were given the opportunity. By the time the full bill took effect in 1976, 2,900 instructors were on board and 17,439 youths had taken the in-person, classroom course. Many schools offered the class as well.

At the core of the program is firearm and hunting safety, things like safe gun handling and situations when it is or isn’t safe to shoot at game. These are topics that youngsters, especially 12-year-olds, might not understand or appreciate. But Hunter Education is so much more. It covers the game laws and regulations and why they exist, the importance of being a responsible and ethical hunter — things that students might not learn at home. The class also teaches the basics of how to hunt and how to track and care for game. And it delves into wildlife identification, behavior, management and conservation, helping foster a greater appreciation of the species the youths will pursue.

“We wanted hunters to have more knowledge, skills and abilities,” Rawlinson said. “So that’s been the premise of the program, and from that comes safety and compliance.”

Safety and Ethics

Hunting incidents didn’t only involve city dwellers.

Russ Mort of Nebraska City has been a Game and Parks conservation officer for 47 years. Like many of his classmates at Pawnee City High School, he grew up on a farm, had experience with guns and spent time hunting.

His father, however, wouldn’t let him hunt with other kids. “He was always scared of me getting hurt,” Mort said. “He said, ‘I doubt if you will shoot yourself, but your friend might shoot you.’”

Mort was among the first graduates of Game and Parks’ new Hunter Safety program, passing the course in 1972 while in high school. His father sat through the class with him. “To be honest, he grew up not realizing things were illegal,” Mort said. “I’m sure he learned that and he wanted to bring me up correctly.

“I know when I took hunter ed, I learned a lot of stuff that I didn’t know before. I learned why there are laws, and you understand the need for laws. I think that’s huge.”

After becoming a conservation officer, he saw hunters’ knowledge and compliance with game laws grow, and he believes Hunter Education played a big part in that. “That’s about the only education we have nowadays, because a lot of the parents, they don’t hunt anymore,” said Mort, who helps teach classes.

When he sees Hunter Education graduates violate game laws, it is often because they are hunting with someone who doesn’t respect the laws and is bowing to peer pressure. But it also goes the other way.

“Kids will influence their parents, too,” Mort said.

“The hunter ed card is pretty important to the kids. That’s one of the first things they pull out of their billfold. It definitely affects how they do things.”

New Requirements, Same Outcome

The Hunter Education program has undergone changes over the past 50 years, including increases and decreases in classroom instruction time, how it is offered, who must take it, and even the name, which has evolved from Hunter Safety to Hunter Education.

One of the major changes was the addition of a mandatory Bowhunter Education program in 1993, addressing a need to educate hunters in a growing sport that required a slightly different skill set.

In 1996, new regulations required anyone born on or after Jan. 1, 1977, to pass a firearm or Bowhunter Education course, a move that would eventually require all hunters to have completed training, as was already the norm in some states. In 2008, recognizing that this requirement might cause those unwilling to invest the time to take a course to simply forgo hunting altogether, and that the majority of accidents involved hunters under the age of 30, the law was changed to require hunters ages 12 to 29 pass a course before hunting. An exemption certificate was also created in 2008, allowing those who have not completed a course to hunt with an experienced hunter, a change made to provide opportunities for individuals who get a last-minute invite to hunt from a friend or family member, possibly helping recruit a new hunter.

In 2001, as youths were becoming more involved in sports and other activities, an independent study course was offered as an alternative to classroom work. In 2013, online courses were offered to meet the requirement for those age 16 and older, and hybrid courses for youths ages 12 to 15 were added. This included an online course and a two-hour Hunt Safe session that emphasizes firearm, archery and tree stand safety, and includes shoot/don’t shoot scenarios.

“Here in Nebraska, we felt kids still needed to get in front of an instructor and handle firearms,” Rawlinson said. “That was a very radical way of looking at Hunter Education.”

Some states have gone entirely to online classes. Studies have shown that even with fewer hours in the classroom, the goal of the program — producing safe hunters — is being met. The IHEA has a set of minimum standards each state meets, but the states develop their own courses and methods of delivery. Since the 1970s, states have informally agreed to honor certificates issued in other states. This reciprocity, important to those wanting to travel, is now being formalized.

A Vital Component

The key to the success of the Hunter Education program has been the volunteers who teach the classes, giving up their free time during evenings or weekends to do so. Throughout its history, there have been thousands of instructors, coming from all walks of life. Twenty-nine of them have been at it for 40 or more years.

“They’re dedicated and passionate and give back to the system, and we couldn’t do it without them,” Rawlinson said. “They’re the most important part of the whole deal because they give thousands of hours every year of their time and talent.”

The involvement of the instructors stretches well beyond the classroom. “The cool thing was when we started Hunter Education, you all of a sudden started getting these volunteer instructors that had incredible hunting and outdoorsman-type skills,” Rawlinson said. “They became part of the hunter ed family and are an integral part of all of our outreach programs.” The volunteers have always been among the first to step up and help out at shooting ranges at the Nebraska State Fair, Outdoor Skills Camps, Outdoor Expos, mentored hunts and more. “They carry a huge load in Nebraska because they’re just that type of person,” Rawlinson said.

The move to online classes has posed challenges. Some instructors felt the move would cheapen the program, and others felt they were no longer needed. “That couldn’t be further from the truth, as hunter ed is going to continue to evolve,” Rawlinson said.

While they spend less time teaching in the classroom, instructors have come to appreciate the ease of setting up a Hunt Safe session and that students arrive knowing the basics, allowing them to focus on key safety elements.

Volunteers have also been key in getting LearnHunting.org off the ground. The program pairs adult Hunter Education graduates with volunteer instructors, who serve as mentors. More than 60 instructors are participating, with more coming on board each year. That program is one of many that are part of the nationwide R3 efforts to recruit, retain and reactivate hunters, something states hope will increase and diversify participation. These goals are critical as it is hunters who, through their purchase of permits and the taxes they pay on guns, bows and ammunition, are the primary source of funding for wildlife conservation and management in the United States.

The hours volunteer instructors contribute are the state’s match to acquire federal funding to support the Hunter Education program. Hours spent teaching Hunt Safe sessions and participating in the Learn Hunting program count toward the hours they need to work to retain their certification each year.

It Works

From 1958, the first year records were kept in Nebraska, to 1977, an average of 20 hunting-related incidents occurred each year, four of them fatal. During the past 10 years, that average has dropped to five incidents and less than one fatality.

“The proof is in the performance for Hunter Education,” said Kyle Gaston, coordinator of the program. “The number of yearly hunting incidents has decreased dramatically. That is the main goal of Hunter Education. It has succeeded.

“It is one of the most successful and scalable educational programs state wildlife agencies have ever offered.

Visit HuntSafeNebraska.org to learn more about the program. Interested in becoming an instructor?

Contact Kyle Gaston, Hunter Education coordinator, at 402-471-6134 or Kyle.Gaston@Nebraska.gov.

The Mentored Youth Hunt Program Endures

By Eric Fowler

Some kids grow up hunting with their parents, grandparents or other family members. Others become interested through other means, be it a friend, something they read, or something they saw on TV or the internet.

Both are required to complete a Hunter Education class. When that task is complete, one of those kids can head back to the field. The other might have no place to hunt, and no one to take them.

Since 1995, Game and Parks and its partners have been helping Hunter Education graduates take that next step with its mentored youth hunt program, allowing them to spend time in the field with experienced hunters.

The program began in March 1995 at Pheasant Haven Shooting Preserve near Elkhorn. Announcements were sent to 800 recent graduates, and 300 youths applied for 45 spots, illustrating the need for such a program. They learned about pheasants, shot clay targets and had a chance to hunt live birds.

That December, five youths were selected to participate in an archery deer hunt on the Lincoln Water System well field near Ashland. Wes Sheets, then wildlife division administrator with Game and Parks and a Hunter Education instructor since 1974, helped organize that first deer hunt and has been mentoring young archers ever since. Last fall, he mentored youths on nearly 50 hunts at the age of 84.

Sheets remembers some youths who would beg to go hunting 25 times a year. He still hears from some of the young hunters he mentored, some just calling to let him know about a recent hunt or the bird dog they got and trained.

“When those stories come along, you just love them because you know you had an impact by putting them in a tree stand a bunch of times,” Sheets said. “Some of the best days of my life have been building relationships with those young people.”

The mentored hunt program has grown substantially since. Hunter Education staff continues to organize archery and muzzleloader deer hunts. Pheasants Forever, a partner in that first mentored hunt, has had more than 16,000 youths attend its youth mentor pheasant and dove hunts since 1996. More recently, it has offered a Next Steps program to pair young hunters and a family member with an experienced hunter to pursue wild birds. Game and Parks conservation officers have organized many turkey, waterfowl and other hunts. Several National Wild Turkey Federation and Ducks Unlimited chapters offer learn-to-hunt programs, as well.

“These programs let Hunter Education graduates put to use what they learn in the course in actual hunting situations,” said Aaron Hershberger, mentor hunt coordinator. “For the ones who don’t have the contacts or resources to do it on their own, that’s really important.”

Now the mentoring program has expanded to help another type of Hunter Education graduate take their first steps in the field: adults. LearnHunting.org, an innovative program developed by Nebraska and other states, pairs new hunters with certified Hunter Education instructors who teach them more outdoor skills, including things like setting up a tree stand, field dressing game and taking them hunting.

“These people have the knowledge, skills and abilities to mentor and to be some of the best mentors in the world,” Rawlinson said. “Some instructors are really liking that. It’s almost hunter ed in its truest form, taking someone hunting.”

Joe Bober – 50 Years and 10,000 Safe Hunters

By Jeff Kurrus

“Dead is dead.”

“Just because it’s legal doesn’t mean it’s right.”

“I almost killed one of my friends.”

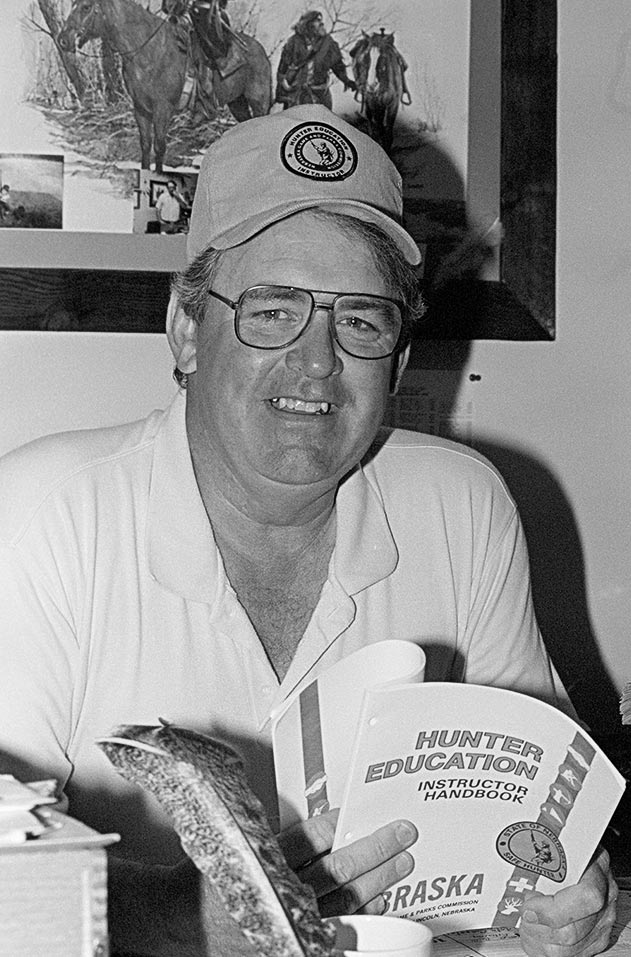

The quotes roll off volunteer Hunter Education instructor Joe Bober’s tongue like he has said them a time or two before. A good guess would say that’s probably true since this is Bober’s 50th consecutive year as a Hunter Education instructor and he has certified more than 10,000 students and 100 future instructors.

Having taught that many students, another fair assumption would be that Joe simply likes to give back. But it’s more than that. “I’m a very selfish person,” he said. “I want them to be safe and knowledgeable. I do it for me. It makes me feel so good when I turn off the light at night because I know that the people I taught are going to be safe, responsible hunters.”

A not-so-safe situation is one of the main reasons Bober became an instructor in the first place. In his early 20s, during a pheasant hunting trip with his friends, it started pouring rain. Bober and his buddies quickly climbed into their vehicle, guns still loaded.

Bober attempted to unload his shotgun, but his wet hand slipped and the gun went off when he closed its action. He blew a hole through the roof of the car, and powder burns covered his friends in the back seat. It scared Bober so much that he almost quit hunting, but it did trigger a desire to help educate others around him.

Over the next few years, Bober began running AKC field trials. He met a number of people, many of them affiliated with the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Among them was Dick Turpin, the first coordinator of Nebraska’s Hunter Safety program.

“He was just starting to get the program off the ground and, in December of 1974, he certified me to teach,” said Bober, who hasn’t missed a year since.

“After I taught my first class, I figured out I wasn’t as smart as I thought I was,” Bober said. He also admitted he learned something new from every class he has instructed. “It’s not about hunting. It’s about right and wrong,” Bober said. “If you got a covey of quail and it’s 3:30 in the afternoon on a really cold day, is it right to break them up when they might not be able to get back together before nightfall? It’s not illegal. But is it right?”

His classes are a mix of hands-on instruction and videos, a reminder of how some things have changed through the years. “When I started, we were using 16mm reel-to-reel film. I got really used to fixing it. Then we went to the VCR. Then the DVD. Now it’s the iPad and laptop.”

Technology has changed the way classes are taught. “When someone didn’t understand something in 1974, they asked Uncle Jake or Aunt Sally,” Bober said. “In 2024, they type it in the iPad. That’s a great thing. But there’s also a drawback because people go to YouTube and learn the wrong way. But students do come in more prepared.”

Bober has also adapted to online Hunter Education classes, something he vehemently opposed initially.

“I teach with passion,” he said. “I explain why I teach. How you can never bring a person back.”

He tells a story about a young girl he knew who was accidentally shot in the spine with a pistol and spent the rest of her life unable to take care of herself. He asks his classes: What would it be like if they had done this to their brother, sister or best friend? How would they feel? “This is when I see the class turn,” he said. “The light bulb comes on. This just isn’t about hunter safety.”

Bober learned that, even with the online course, his passion would come out when he got those students in an in-person Hunt Safe session. “One of my prize moments,” he said, “was when I had four University of Nebraska-Omaha students show up to class. But they had no desire to get their Hunter Education certificate. ‘Our professor had his son take your class,’ they said. ‘How you teach with passion was why we were sent here.’”

Because of his passion, Bober has no plans to stop teaching anytime soon, and the quotes keep coming with each lesson he provides.

“The only person I’ve ever seen with eyes in the back of their head was my mother. And that is why you have to have proper shooting zones.”

“Hunting is the only sport you play with no referees. You have to know right from wrong.”

“Whether you’re 11 or 73 years old, you are an adult when you have a gun in your hand. So you and your buddies need to act like adults.”

Every once in a while, even after thousands of hours in the field and in front of students, Bober runs across a question he can’t answer. “No problem,” he said. “If I can’t answer it, I know someone who can.”

Brenda Fulk – Not Just for Boys

By Justin Haag

Brenda Fulk of Mitchell has long known that hunting is not just for the boys.

“More women are hunting and shooting than 25 years ago,” she said, thinking back to when she was certified as a Hunter Education instructor in 1999.

Statistics back that up. An estimated quarter of hunters in the U.S. are now women, and they’re often referred to as the pastime’s fastest-growing demographic. When Fulk started, only 3 percent of Nebraska’s Hunter Education instructors were women. That number, 28, has since doubled. The 56 women teaching Hunter Education in the state today represent 11 percent of the total.

Game and Parks welcomes female perspectives in the classroom and on the range. Of course, we’ve known that women are as capable shooters as men since Annie Oakley became an international sensation, but anatomical differences make the process dissimilar between genders.

“Women hold firearms a bit differently and the sights sometimes don’t line up,” she said. “The male instructors don’t always understand that.”

She knows one of the male instructors well. Her husband, Brad, has attained the title of master instructor. The two have taught courses at sites throughout the Panhandle, passing on the knowledge they’ve learned in the field. That knowledge and love of hunting was also passed on to their four now-adult sons.

One harrowing experience stands out in Brenda’s mind and has prompted her to emphasize teaching the budding hunters in her classes to be prepared.

In September 2012, she was hunting doves with her youngest son and his friend when they discovered the body of a man who had been missing for four days in a canal that crosses their Sioux County ranch.

She said it was a traumatic experience, but she uses the experience in the classes to this day, stressing the importance of being aware of location and surroundings, having ample supplies, and having a plan to contact help in an emergency when in the field.

“I talk about how rural of an area we live in. You cannot put our address in GPS and get to our house,” she said, illustrating the necessity of these lessons and how every hunter should take them seriously.

Her memories of the outdoors and the classroom are positive. Brenda said she and Brad are teaching the children of those who took their classes years ago. The couple doesn’t have plans to stop doing it anytime soon.

“We will keep teaching until we can’t anymore,” she said.

Jade Wawers – Teaching the Next Generation

By Jenny Nguyen-Wheatley

Every hunting season since Jade Wawers was born, she’s been out in the field with her parents chasing deer, pheasants or waterfowl. The eldest of four girls, Wawers caught the hunting bug the hardest. She began working at the Dick Turpin Education Center at age 17 and, at the time, knew she wanted to make a career of studying wildlife and helping future hunters.

“The second I turned 18, I was asked to become an instructor. I knew about hunting and hunter safety,” Wawers said. “It was a great way for me to get more involved with the agency and what they do for hunting and hunters.”

Wawers, now 25, keeps busy as a master’s student at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln working on a wild turkey monitoring project. Her research often pulls her to western Nebraska, sometimes as long as seven months out of the year. She’s conducting a trail camera study to evaluate the distribution and composition of mesopredator communities in Nebraska and how they affect wild turkey populations.

Turkey also happens to be her favorite game to hunt. “I hear a lot of people say that turkeys are dumb — that they’re a stupid bird,” Wawers said, “but try hunting them and you see how smart and clever they can really be.”

Although Wawer’s job as a UNL wild turkey technician keeps her busy, she continues to teach Hunter Education one to three times per year, from two-hour Hunt Safe sessions to the longer 8-hour classroom courses. She prefers the longer format, as it allows time for students to practice on the firearm or archery range. They’ll also practice crossing fences, and she might even simulate a blood trail or do a mock pheasant hunt to get students engaged.

In 2022, she recognized a need for an adult-only classroom and organized a Hunter Education course for college students and other prospective hunters age 18 and older. Most prospective hunters her age don’t necessarily want to take a class with a “bunch of 11-year-olds,” she said. Not only was the adult class well-received, it was also one of her more memorable experiences as a hunter education instructor.

“I love teaching adults because they are capable of going out and hunting after the class, so you can keep up with their success stories. They’ll send me pictures of their first deer, first turkey … It makes me so incredibly happy and proud to see them going out,” Wawers said. In contrast, she doesn’t necessarily receive the same follow-up from younger students who attend classes under the mentorship of their parents.

Hunter Education instructors aren’t paid for their time. Wawers says she teaches because she wants to be a part of bringing along the next generation of hunters.

“Safe hunting is something that can be overlooked,” she said. Hunter Education should be taught early, and sometimes, parents need the reminders, too.