By David L. Bristow, Nebraska State Historical Society

Nebraska frontier life involved hardship, deprivation and … luxury?

One of the striking things about pioneer narratives is the important role of luxuries where such things were hard to get. When Nebraska Territory opened to settlers in 1854, a string of crude villages sprang up quickly along the Missouri River. People staked out farms and town lots and lived in tiny cabins or dugouts while they speculated in real estate and dreamed of the future. For the first few years, “Everybody considered himself rich or likely soon to be,” in the words of early Omaha historian Alfred Sorenson.

Mrs. Fenner Ferguson, wife of the first chief justice of the Nebraska Supreme Court, had a piano shipped from St. Louis in 1855. Her daughter-in-law later recalled that “Mrs. Ferguson’s piano was one of her greatest comforts in those early days. I have often heard her say that many times when she would be practicing, the room would suddenly become darkened and she would find the Indians looking in at the windows to see and hear what was going on. She often asked them in and played for them.”

On New Year’s Day, 1855, Acting Gov. Thomas Cuming bought a basket of eggs so his wife could make “Virginia egg nog, Mrs. Cuming being a Virginian.” While sipping the beverage, Cuming joked that the eggs were “extra fine” and quoted the price — a dollar an egg, roughly $37 in today’s money. It isn’t clear how Mrs. Cuming reacted to that news, but she was still telling the story 50 years later.

That winter, Tom Cuming suggested holding an “executive ball” for incoming Territorial Gov. Mark Izard. It was at Omaha’s City Hotel, a single-story frame building at 11th and Harney streets. The weather was so cold and the building so drafty that ice formed on the floor after it was scrubbed. Few women lived in Omaha at the time, and only nine ladies attended the ball. The band consisted of a solitary fiddler from Council Bluffs. During the dancing, several people slipped and fell. Gov. Izard was from Arkansas and not used to Nebraska winters. He “stood around shivering with the cold, but bore himself with amiable fortitude.”

By the latter 1850s, Omaha still “looked as though falling down from the skies onto the bare plains,” in the words of Emily Doane, wife of the new district attorney. The streets, she recalled, were “mostly a sea of mud” with only one sidewalk in town, but Doane also wrote of social events at the Herndon House, the city’s finest hotel:

“At the dances and evening parties, it was most unusual to see a man not in full dress suit, while women wore spreading skirts containing yards and yards of material, and the low-cut bodices of Victorian times. The skirts were long and had trains, for no lady would have allowed an ankle to be seen in those days … .”

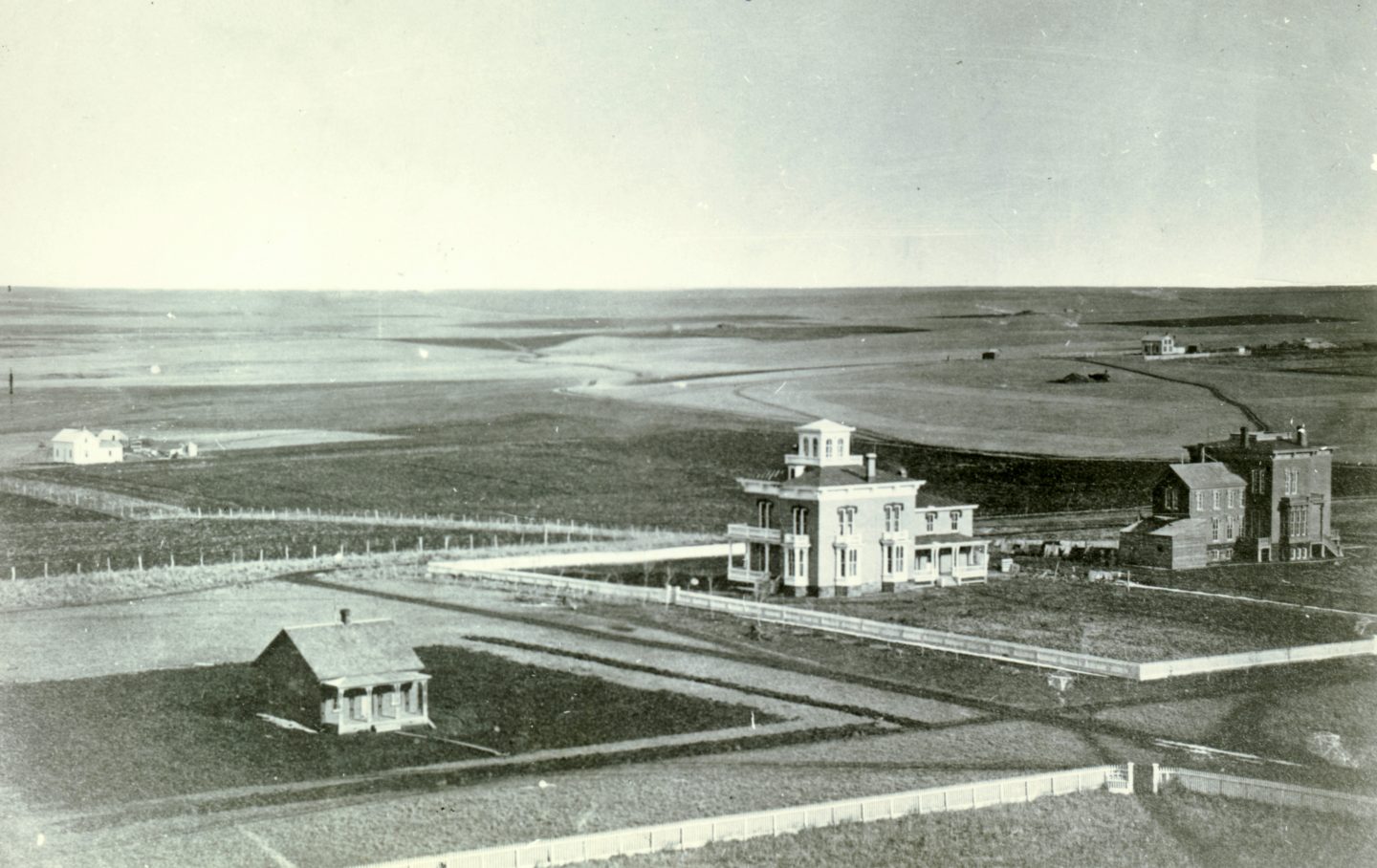

In each of these stories, people accepted inconvenience or great expense to recreate something from their old life back east. But sometimes extravagance had a political point, as in 1869 when Thomas Kennard and a few other prominent men built expensive houses in the new state capital of Lincoln. At the time, many people doubted that the state government would remain in such a tiny, out-of-the-way village. Spending money on a fancy house demonstrated confidence and prompted others to invest in the would-be city.

Even folks far from the capital worried about public opinion — as photographer Solomon Butcher found out when he visited the David Hilton homestead in Custer County in 1887. Historian John Carter writes that “the family still lived in a sod house, a situation of considerable embarrassment to Mrs. Hilton — so much so that she steadfastly refused to be photographed in front of it.

“To make the picture to her liking, Mr. Hilton and the photographer had to drag the pump organ out and away from the house so that she could show friends back east that she had one without revealing the condition of their dwelling.”

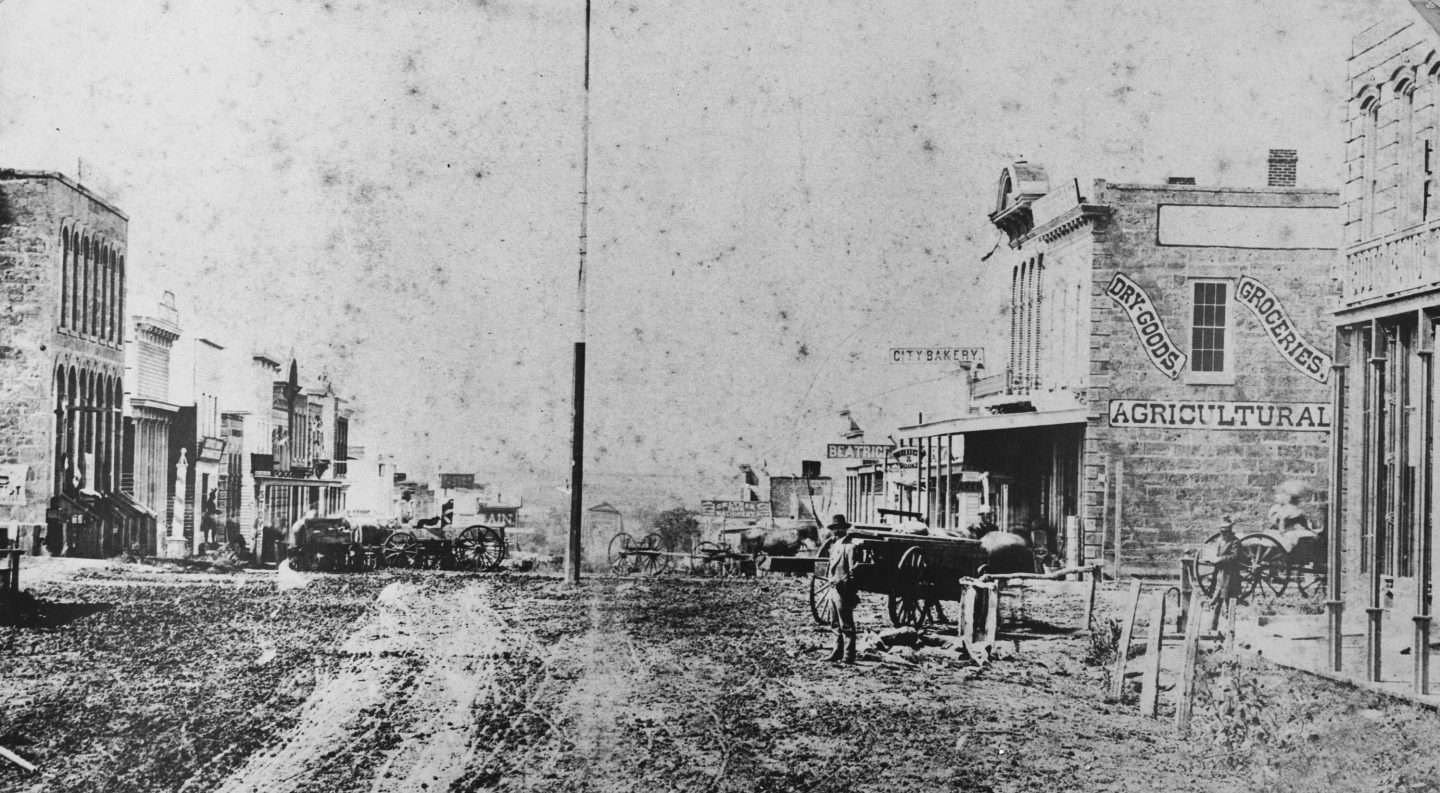

Sometimes refinement had more to do with the kind of society that people hoped to build. Beatrice, for example, was still a rough frontier town in the 1870s when a group of local residents led by suffragist Clara Bewick Colby decided to open a library.

A letter to the Beatrice Express argued that a library was necessary to “give tone to the community while still in its youth, and to bring in more of those of whom we can never have enough, i.e., people who ask what opportunities the place affords for mental culture.”

We tend to assume that pioneers were a rough lot (and sometimes they were) or that they were plain-living people who spurned luxury — although that was often out of necessity rather than choice. Few Nebraskans could afford some of the extravagancies described here. But the taste for refinement reveals how people not only comforted themselves with nice things, but also how they looked to the future, not seeing their crude present reality so much as their dreams of future prosperity.

Visit NSHS’s website at history.nebraska.gov.