By Justin Haag

Historians often tell of Fort Robinson’s period of producing the trusty steeds of the cavalry as a remount depot for the U.S. Army in 1919-1945. The fort’s role in rearing aquatic species that bolstered the region’s fishing heritage during that era gets less attention.

During the 20th century, Crawford and Fort Robinson became an integral location for producing the fish that found their way to dinner tables of the Midwest and High Plains. Most of the ponds that visitors enjoy today were created to serve aquaculture as Crawford was part of the U.S. government’s federal fisheries program for more than half a century. They stand as a reminder that the Crawford city park was home to a first-class fish hatchery from the late 1920s until a devastating flood in 1991.

Hatching a Hatchery

As the U.S. government was looking to remedy depleted fisheries resources across the nation in the late 19th century, it developed the National Fish Hatchery System. The Crawford operation was established as a substation of the Spearfish hatchery in South Dakota’s Black Hills, which had been operating since 1896. The U.S. Department of Defense issued a permit to the Department of Commerce in December 1927 for the construction of fish nursery ponds on Fort Robinson property. The request to do so had come in the form of a two-page letter from none other than Herbert Hoover, who was U.S. secretary of commerce at the time and would become the nation’s 31st president two years later.

Henry O’Malley, U.S. commissioner of fisheries, wrote in his 1928 annual report that construction had begun on “a new combination trout and pond station” at Crawford as a subsidiary to the Spearfish hatchery.

Much of the early construction was on the main hatchery grounds at the city park, including buildings, ponds and a water line from springs at Fort Robinson. By 1933, Crawford had grown to become a stand-alone operation.

From 1933 to 1935, the hatchery capitalized on the ready labor of the Civilian Conservation Corps, which had established a “drought relief company” camp at Fort Robinson as part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal to provide employment opportunities during the Great Depression.

Just as it had done throughout the nation, the corps, known as the CCC, left a lasting impression in the Panhandle through its many projects. Among them were construction of cabins at Chadron State Park and the lighthouse-styled observation tower at Lake Minatare. The largest of the projects at Fort Robinson was for irrigation — what we now know as Carter P. Johnson Reservoir.

A CCC newsletter from May 1935 tells that the 470-foot “Noel Dam” on Soldier Creek was nearing completion. Surely, the workers would have enjoyed having equipment that would be used for the lake’s upcoming renovation, as constructing the dam and excavating the reservoir with Fresno scrapers proved challenging that winter.

“At first the work was all pick and shovel until the flow pipe was laid,” the newsletter’s author stated. “Then four mule teams with Fresnos were added followed by four caterpillar tractors with Fresnos to speed up the movement of dirt. Every night a crew of six men kept fires burning to keep out frost and thaw the ground. Work progressed with day crews as large as 40 men to speed the work and in an effort to be ready to impound the spring rains.” The construction was a success, and with ample rain that year, the reservoir filled quickly.

According to the newsletter, the corps initially named the resulting 20-acre reservoir Lake Bertha to honor the wife of Louis Bash, a quartermaster general who had recently visited Fort Robinson. At some point, naming honors instead went to Carter P. Johnson, the cavalryman who served five tours of duty at Fort Robinson while advancing through the ranks and building a storied military career. Having retired as a major in 1909, and taking up residence on a nearby ranch along the White River, Johnson returned to the fort for a short stint as commanding officer in 1916 — the same year he died of heart problems. His colorful reputation is reinforced in a painted portrait by renowned 19th century artist Frederic Remington.

Putting in Ponds

The conservation corps was busy in ’35. An annual report from hatchery foreman Fred Engelhardt said the work included “concrete outlets for two nursery ponds on Cherry Creek, lower ice pond dam of earth and spillway, concrete outlet, earth dam and spillway for lower Grable Springs bass pond. One half mile drainage ditch from Grable ponds to Grable Reservoir.”

They also “began repair work on lower ice pond dam and spillway, damaged by erosion caused by a cloud burst early in June.”

Historical documents also tell of the CCC constructing numerous dams along Soldier Creek. Although not specified, the Wood Reserve Ponds, near the fort’s old timber and sawmill operation, and Crazy Horse Pond, named for the highly revered Sioux war leader who was killed while being detained at Fort Robinson in 1877, were likely among them.

In 1936, Engelhardt wrote that station personnel graded bottoms and banks of two “Grable Spring trout nursery ponds.” With corps labor, they also rebuilt the “lower ice pond dam and completed the spillway with concrete floor and side walls at discharge end of the spillway, riprapped upper ice pond spillway and rebuilt Grable Spring pond number three dam.”

Sometime since Engelhardt’s reports, the spelling of Grable changed to Grabel in documents. Also, the “ice ponds” became known as Ice House Ponds and Grable Reservoir became Lake Crawford.

The Old Ponds

Records indicate the Ice House Ponds and Lake Crawford are the earliest of the fort’s impoundments.

Lake Crawford, which was originally called Grable Lake, is named for an enterprising family from the late 1800s that became known nationwide for its efforts to develop the West. Regrettably, those efforts seemed to end in scandal.

The Crawford Tribune of the 1890s featured many headlines conveying excitement about Francis C. Grable and his nephew Charles J. Grable and their work in developing irrigation infrastructure in the White River Valley and gold mining and smelting operations in nearby Edgemont, S.D. Grable Lake was part of those efforts.

Francis C. Grable, an Ohio native, had connections to the railroad and had early dibs on townsites between Alliance and Deadwood, South Dakota. He also had connections to wealthy aristocrats on the East Coast and brought them to the West by train for tours, convincing them to buy stock in the operations.

The two promoters were founders of the State Bank of Crawford, Francis first serving as vice president and later president, and Charles as cashier. Newspaper accounts of the “Grable boom” tell of the men as charismatic characters who were working hard to bring prosperity to the region.

“[Francis] Grable brought into existence more mining, smelting, manufacturing and like projects it has been estimated, than any other one man in the world,” wrote an Omaha World-Herald reporter. “He floated all these schemes on money obtained from eastern capitalists.”

The whole operation crashed February 1898 when the cashier at the Chemical National Bank of New York admitted to the bank’s president and board that he had loaned Francis Grable $243,000 — about $8 million in today’s figures — without authorization. Headlines in metropolitan and small newspapers throughout the nation promptly told of the Grable “schemes” on their front pages. Although the Grables said the projects would realize returns soon, the investors

backed out.

The Grables immediately departed the region, the bank closed, the projects were abandoned, and the Grable reservoir dam would not be completely finished until 1930 when the new fish hatchery included it in its appropriations as a pond for rearing bass.

The reservoir must have been far enough along to hold some water upon the Grables’ departure, though.

“Some very fine ice has been put up in Crawford this week, cut from the Grable lake south of town,” stated a January 1901 one-sentence news report in the Tribune.

Prior to modern refrigeration, ice was harvested during winter and stored for later use. At Fort Robinson, reports indicate it was cut from the Ice House Ponds and housed in a wooden building between Soldier Creek and the fort’s veterinary hospital, near what is now U.S. Highway 20. Reportedly, the building was later sold and moved to Agate Springs Ranch south of Harrison.

While the Ice House Ponds remain an attraction, the Grable Lake, or Lake Crawford, has long sat empty because of damage to the dam and outlet structure. The other ponds named for the family, which were constructed for the hatchery and likely named such as a matter of convenience, have been transformed to one of Fort Robinson’s most popular fishing spots.

In the decade following his departure, Francis Grable focused ambitions to the area north of Fort Collins, Colorado, developing irrigation ditches and roads. Those efforts were halted when he was arrested in 1912 after being tied to a bank embezzlement scheme. After a judge dismissed Grable’s case, he moved to Clermont, Florida, and entered the citrus industry. It was later reported the city of Clermont was so thankful for his contributions to the region that it gifted him with a trip to Europe.

Despite the legal problems, he was regarded as an irrigation pioneer in northern Colorado and retained popularity. He returned to Fort Collins from 1931-1936 and wrote a newspaper column titled “Reviewing the Years.” A column about his efforts at Crawford and Edgemont was not found during this research.

He died in Florida in 1944.

Diverse Production

Boosted by the ponds’ capacity, the Crawford hatchery had one of the most diverse missions in the nation. Early reports tell of its successes and failures in producing brook, rainbow, “black-spotted” (cutthroat) and “Loch Leven” (brown) trout, catfish, bream, sunfish, “black” (largemouth) bass, yellow perch and crappies. Of the 91 stations and substations listed in the system’s 1933 annual report, only five other hatcheries were producing a more diverse set of species than Crawford.

Fort Robinson may have been one of the nation’s best places to be during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Not only were the CCC’s activities building excitement, but the fort also hosted the Army Equestrian Olympic Team as it prepared for the 1936 games in Berlin. (Equestrian for what was termed the “Nazi Olympics” later ended with suspicions of foul play, as the host Germans claimed an unprecedented and not since repeated sweep of all six gold medals.)

The fort’s role in producing horses and fish was symbiotic in at least one regard. Surplus from the fort’s thousands of horses and mules provided a supply of meat that was converted to fish food. While other hatcheries across the nation were advertising to purchase horses to feed the fish, Crawford enjoyed a free supply of as many as a dozen horses per month. Documents indicate it was something of a trade for keeping the fort’s streams and lakes stocked for the military personnel who liked to fish. In 1942, the hatchery reported receiving 30,000 pounds of horsemeat.

Making fish food from animal products — sheep liver and beef hearts also were commonly used — was messy and labor intensive. In the 1960s, dry pellets revolutionized the way hatcheries feed fish.

Upstream Battle

Although hatchery staff was grateful to the fort for allowing ponds on the property, the distance from the main grounds could be problematic. Each of the ponds was upwards of 10 miles away. One year, after a period of heavy snowfall, hatchery staff reported filling backpacks with fish food and plodding on snowshoes to certain ponds to keep fish alive.

Clarence Storbeck of Chadron, a longtime assistant supervisor in Crawford, said hatchery employees stocked the abandoned cellar of the Wood Reserve’s officers’ cabin with overnight necessities in case weather left them stranded.

In late summer of dry years, water at some of the ponds would get too low and fish would require salvaging. One especially challenging period was during World War II when the fort’s 1,000-man prisoner of war camp was constructed near the Cherry Creek ponds. Not only did the “blitzkrieg” of construction result in eroded sediment piling up in the Cherry Creek ponds, but also the water was diverted away from the Grabel Ponds to meet the demands of the new facilities.

The period brought another set of challenges. With hundreds and thousands of stock dams being constructed on farms and ranches at the encouragement of the Soil Conservation Service, the Crawford hatchery had a hard time keeping up with requests for fish.

The hatchery’s original service region included all of Nebraska, all of Wyoming, areas of South Dakota west of the Missouri River, and parts of Colorado. Of course, Crawford was not the only hatchery in Nebraska. The state’s Game, Forestation and Parks Commission produced millions of fish at hatcheries near Gretna, Parks, Valentine and North Platte. Records show the Crawford facility had a positive working relationship with Nebraska’s state fisheries.

It was often noted with gratitude that state employees provided pick-up and delivery of fish from Crawford.

A Popular Place

The hatchery was popular with visitors ranging from schoolchildren to distinguished dignitaries, reporting more than 12,000 visitors per year by the early 1950s.

A publicity flyer produced between 1957 and 1974 boasts that the Crawford Hatchery, then one of more than 90 such facilities across the nation, was producing in excess of 2 million fish per year for stockings in Nebraska, South Dakota and Wyoming. By that time, the facility had narrowed its scope to largemouth bass, bluegills, rainbow trout and brown trout.

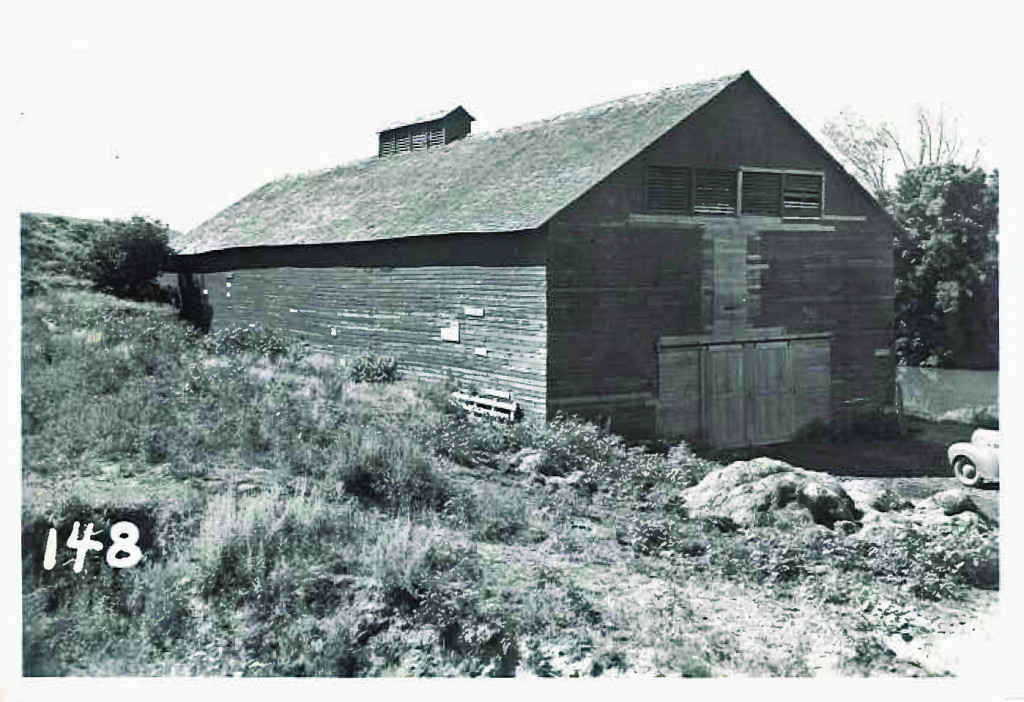

“Several 1- to 3-acre earthen ponds on the Fort Robinson Reservation are used by the Crawford Hatchery to produce largemouth bass and bluegill sunfish for distribution to approved ponds and lakes,” the author wrote. “The ponds are scattered over a wide area so it is generally not convenient for visitors to observe these operations.”

Torrents of Change

The Spearfish station would later be named for D.C. Booth, who was its superintendent during the era of the Crawford site’s inception. Today, the D.C. Booth Historical National Fish Hatchery & Archives stands as an impressive interpretive facility that annually attracts more than 160,000 visitors and houses many of the records from the Crawford hatchery that were used for this report.

Because of budget cuts, the Crawford Hatchery was abandoned by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1984 and the Game and Parks Commission took over its operation. With support of the Legislature and Gov. Bob Kerrey, Nebraska established the Trout Stamp to fund the operation.

Game and Parks switched it from a brown and brook trout facility to brown and rainbow, and, for the first time, the fish from Crawford were distributed exclusively to Nebraska waters.

Unfortunately, the Crawford hatchery’s era under Game and Parks was short-lived. On May 10-11, 1991, the hatchery and many other structures in the valley were destroyed when 12 inches of rain in a six-hour period caused a 15- to 18-foot wall of water to strike parts of Crawford. The ponds at the hatchery filled with mud and thousands of brood stock, fry and fingerlings washed downstream — most of which surely died.

While remnants of the hatchery still stand at the Crawford city park, the facility never reopened and Game and Parks has relied on its five other hatcheries — Calamus, North Platte, Rock Creek, Valentine and Grove — for the bulk of its fish production.

The hatchery’s ponds, however, remained an asset at Fort Robinson. With the facility destroyed, all the ponds opened to the public for fishing at the northwest Nebraska tourist attraction, having transformed to a state park in the 1960s.

The Trout Stamp also went away, but the Aquatic Habitat Stamp was implemented in 1997 to fund fisheries projects throughout the state. One such project includes the impressive pond renovations being realized at Fort Robinson today.

Things are a little different from the ponds’ beginnings, but, in a way, they are still doing what they were originally designed to do. With the recent investments, they are sure to continue putting fish on the table and contribute to the state’s fishing heritage for generations to come. ■