By David L. Bristow, History Nebraska

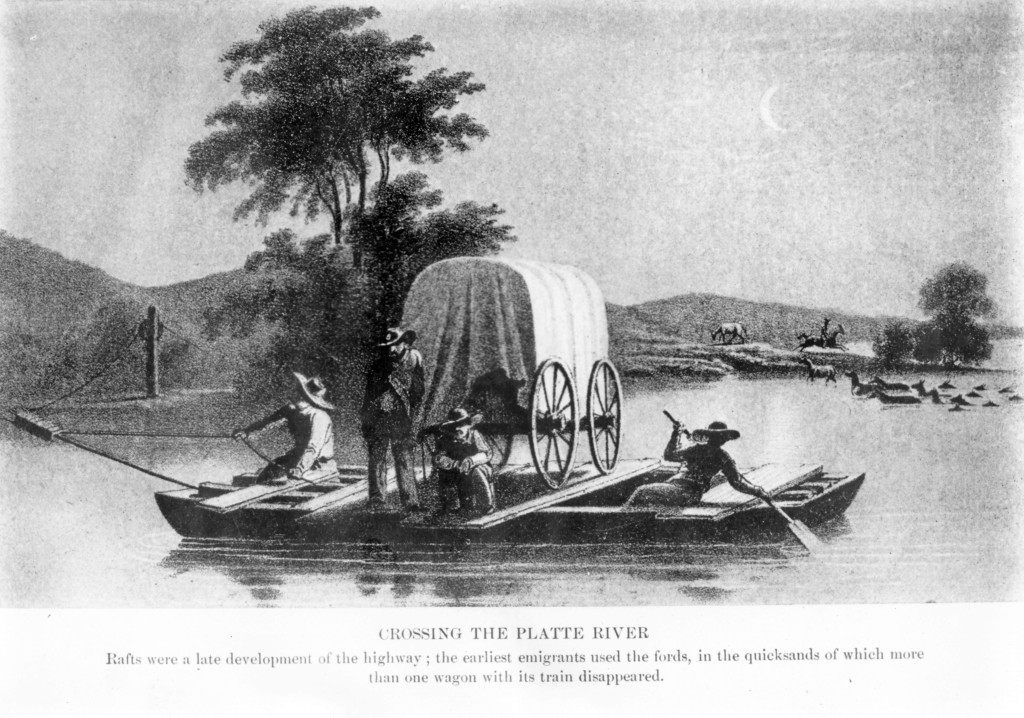

This is our experience crossing Platte River; the meanest of rivers — broad, shallow, fishless, snakeful, quicksand bars and muddy waters — the stage rumbles over the bottom like on a bed of rock; yet haste must be made to effect a crossing, else you disappear beneath its turbid waters, and your doom is certain,” so reads an 1862 emigrant diary quoted by historian Merrill Mattes in his landmark book, The Great Platte River Road.

Mattes writes that some travelers referred to the “Coast of the Platte” because the broad river on its sandy bed looked almost like an ocean shoreline in the distance. He quotes a traveler named James Evans who saw the river swollen with spring rains and snowmelt:

“From the sandhills, it had the appearance of a great inland sea. It looked wider than the Mississippi … Judge my surprise when I learned that it was only three or four feet deep … The water is exceedingly muddy, or I should say sandy, and what adds greatly to the singular appearance of this river, the water is so completely filled with glittering particles of micah or isinglass that its shining waves look to be rich with floating gold.”

No bridges spanned the Platte during most of the overland trail era. In 1876, the Camp Clarke Bridge (below) opened near present-day Bridgeport. Spanning the North Platte River, the 2,000-foot wooden truss toll bridge served travelers during the Black Hills gold rush.

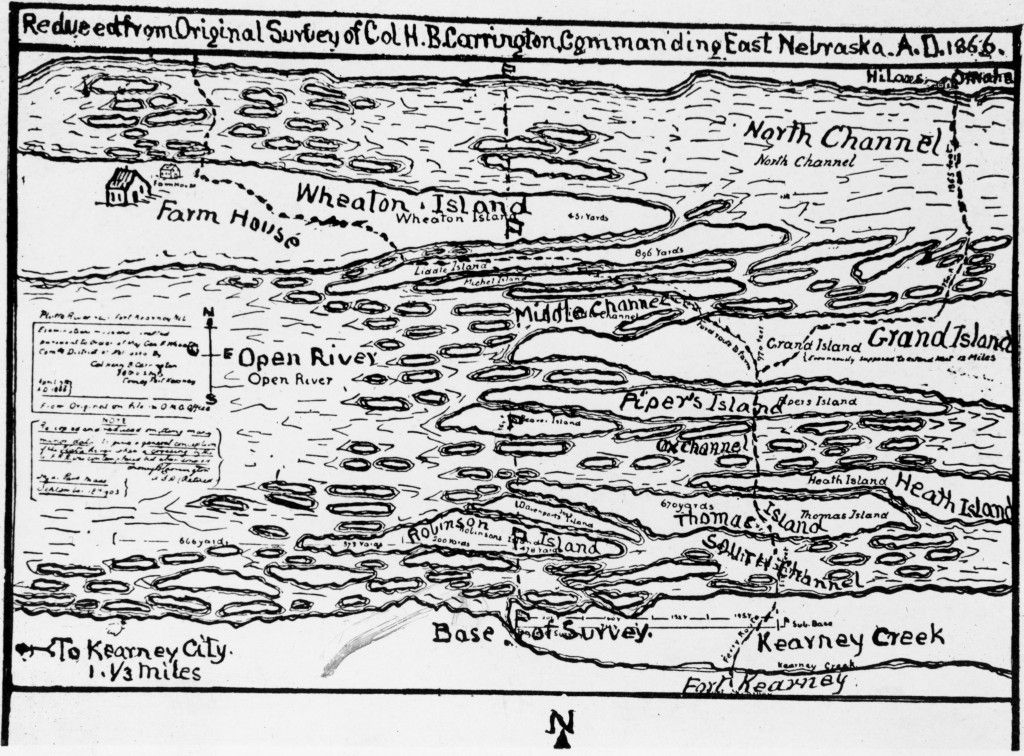

How difficult was it to cross the Platte without a bridge? The 1866 map on page 34 gives you some idea. The river was notorious for its braided channel and patches of quicksand. The map shows the best places to ford.

But some of the map’s labels are confusing to modern eyes. What is Kearney City (lower left) doing south of the river and west of the fort? And what’s this about Grand Island being north of the fort? Kearney City, informally known as Dobytown for its adobe buildings, was described by an 1860 visitor as a “gambling hell” populated by “as bad a crowd of men and women as ever got together on the plains.” The present city of Kearney was founded in 1872 north of the river.

Grand Island, meanwhile, was a long island between channels of the Platte. It was named “La Grande Isle” by 18th century French traders. The city originally known as Grand Island Station was founded the same year this map was drawn, but well to the east.

Now, consider a 4-foot-high, 100-pound steamboat anchor (right) from History Nebraska’s collection. In 1985, Gloria Liljestrand-Barber found it mostly buried on her parents’ farm near Brady. In the 1890s, a similar anchor was discovered three miles away. Both anchors were not far from the shifting channels of the Platte River.

Does this mean steamboats were navigating the Platte? Legend has it that the steamboat El Paso traveled up the river in 1852, but the story never seemed plausible to most historians. Even shallow-draft steamboats of that era usually drew at least 4 feet of water, but the Platte’s braided channels were frustrating even in fur trade-era canoes or bullboats.

Apparently, the anchors arrived by train, not by steamboat. In 1866, the army built a pontoon bridge near Fort McPherson, and Civil War-era bridges used steamboat anchors to hold the pontoons in place.

The Brady anchor, in other words, tells a story not of steamboat travel, but of the transcontinental railroad and of stagecoaches, freight wagons and other traffic along the Great Platte River Road. And because Fort McPherson was involved in military campaigns during the Indian Wars, the anchor speaks to the conquest of the Plains and the dispossession of Native tribes.

Like the anchor, the Platte River has many stories to tell. Just getting from one side to the other was an adventure.

Visit History Nebraska’s website at history.nebraska.gov.