By David L. Bristow, History Nebraska

We take bridges for granted, but river-crossing Nebraskans mostly relied on ferries into the 20th century. The ferry was a seasonal operation. When the river iced over, you could simply drive your team across, as long as you trusted the thickness of the ice.

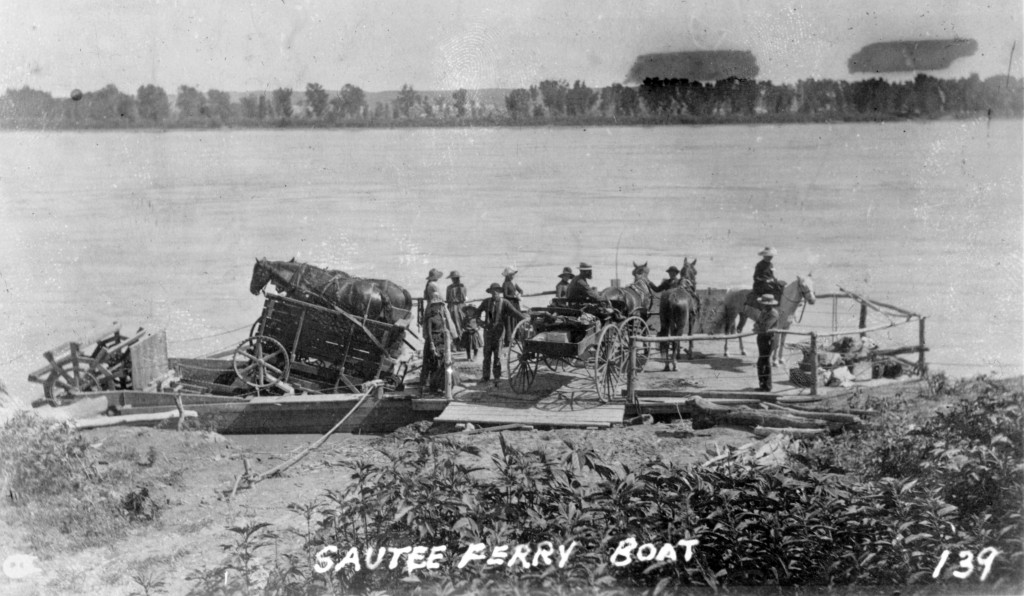

During the westward migration along the Oregon, Mormon, and California trails, emigrants first had to pay ferrymen to take them across the Missouri River. Early ferries were rafts propelled by poles or oars. Cable ferries were an improvement, and “team boats” propelled by horses on a treadmill were faster but less common.

Nebraska Territory opened to Euro-American settlement in 1854. That year, former fur trader Peter Sarpy of Bellevue bought a 165-ton steam ferry to better serve the expected flood of settlers. Also that year, the Council Bluffs and Nebraska Ferry Company built Omaha’s first brick building to serve as the territorial capitol. It was an investment to ensure continued ferry traffic.

In Omaha, ferry use did not end with the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad. The Missouri River remained unbridged until 1872. A special steamboat had a length of railroad track running from bow to stern so it could ferry railcars.

Along the Platte River south of Schuyler, Moses Shinn and his son, Dick, built a cable ferry in 1859. Shinn’s Ferry used the river itself to propel the ferryboat. It was a “reaction ferry,” a type of cable ferry that angles the boat so that the current pushes it laterally. Bridle cables on either end of the boat were attached to “travellers” that would slide along the overhead cable. The diagram (below) shows how it worked.

To the west, the shallow Platte was crossed only by fording until bridges were built. Along the Missouri, ferries for wagons and, later, automobiles, remained in use long after railroad bridges spanned the river. For example, for many years, there was no convenient way for southwestern Iowa farmers to reach the South Omaha stockyards with truckloads of livestock. The Douglas Street Bridge was the nearest crossing. Diesel or gasoline-powered ferryboats, such as the one shown above, provided transport.

Despite demand, ferry businesses struggled to survive in Bellevue. Blame the ever-shifting channel and banks of the Missouri River. A well-prepared landing could be rendered unapproachable by shifting sandbars, and building a new landing also meant building a new road. The completion of the South Omaha Bridge in 1936 finally rendered the Bellevue ferry obsolete — a story similar to other ferries shown here.

Visit History Nebraska’s website at history.nebraska.gov.