By David L. Bristow, History Nebraska

By the mid-1870s Nebraska’s open-range cattle industry … was experiencing growing pains,” writes historian Jim Potter. In the Platte Valley and the Panhandle, people worried about the “introduction of Texas cattle to supply the Indian agencies, unregulated ‘round-ups’ that caused ownership disputes (in winter, long hair made brands hard to see), and bulls running at large year round.”

In early 1875, cattlemen met in Ogallala to organize the Stock-Growers Association of Western Nebraska. At the group’s request, the state legislature authorized stock inspectors and limited the roundup period to May 15 through November 15.

The association then organized their first official roundup to begin in Sidney on May 15. One party followed Pole Creek up from Sidney and eventually worked east down both the South and North Platte rivers. A second party worked west from North Platte as far as Ash Hollow.

What was such a roundup like? Potter found a lively eyewitness account of the following year’s roundup in the North Platte Western Nebraskian of June 17, 1876:

“… The cattle [were] sighted, scattered here and there in bunches, ranging from five to two hundred head, which at sight of a horseman would break and run. Then comes the excitement — up gulch, down canyons, over hills and table-lands, on a long steady run, in their vain efforts to escape from the boys who are pursuing them, horses and riders equally thrilled with the excitement of the chase; ’tis grand, exhilarating, and as the cattle are overtaken, checked and put with another bunch or bunches, they are then driven to the rodeo ground.

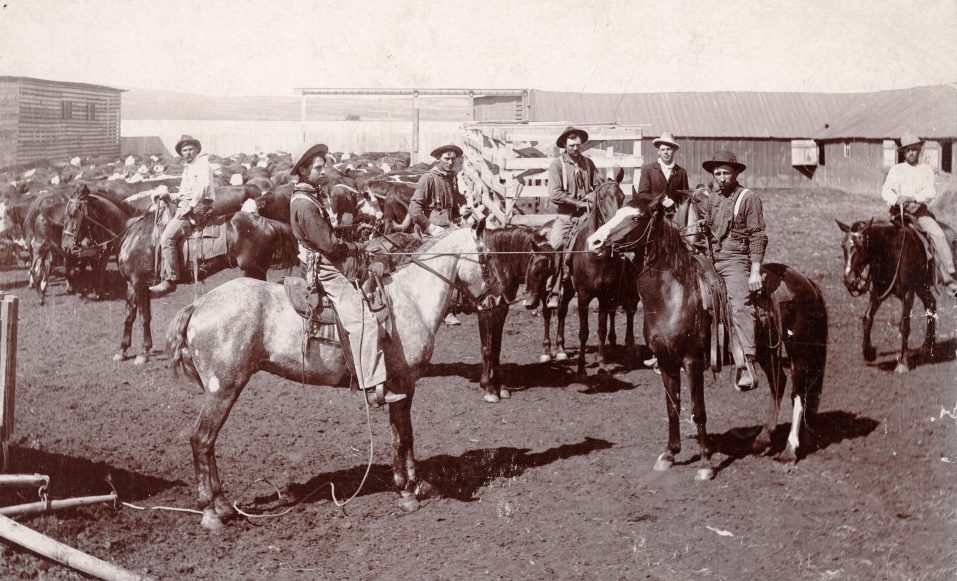

“Then comes the separation or ‘cutting.’ A band of a thousand head [is] surrounded by twenty horsemen or more. One party, employees of the owner, enter the herd, select the animals bearing the owner’s brand and mark, cutting each animal from the main herd and making a bunch of that brand until all are separated.

“This ‘cutting’ is exciting work. Now going at full speed as the animal makes an effort to get again with the main bunch; now stopping and wheeling as quick as a flash of lightning, dodging, twisting, until the animal perceives the folly of its efforts and permits itself to be driven to the bunch or brand where it belongs.

“No horsemanship can excel that which is displayed by an experienced cow-boy. As they dash over the rough prairie at the top of their mustang’s speed, [avoiding] great numbers of holes, the work of prairie dogs and our family of sub-soilers, the utter disregard of their peril is something as courageous as it is rash.

“The training of the ‘cutting’ horses is something wonderful. No matter what distance the cutting horse has traveled, how fatigued it may be, the moment you ride it into the herd every muscle, every faculty, is on the alert and the intelligence they display is something almost human; and occasionally you hear a cow-boy speaking of his favorite, ‘He knows more than most of men,’ is the usual expression.

“All the cattle separated, each man holds his brand separate, another bunch is gathered and separated until night. … Such is the routine, each day having its incidents. In case of dispute as to who owns an animal, the animal is lassoed, thrown down, and all marks examined and the ownership is readily proven. A great many true gentlemen can be found among these wild fellows, men that are honest, intelligent, and when one offers his friendship, it is a friendship that will stand all tests.”

Visit History Nebraska’s website at history.nebraska.gov.