By Kirk Steffensen, Missouri River Program Manager

Paddlefish are a group of ancient fish species with fossilized records dating back approximately 125 million years. They are one of the largest and longest-living freshwater fish species in the world, with a lifespan of 30-plus years, and are easily recognizable by their elongated rostrums — beaklike snout — and lack of scales.

Filter feeders, paddlefish swim with their large mouths open and filter the microscopic plankton, mainly zooplankton, out of the water. Therefore, conventional fishing methods of baiting are ineffective. Paddlefish are generally captured by snagging, which requires casting and forcefully pulling a hook through the water until you “foul hook” a paddlefish. Paddlefish in Nebraska can, on rare occasions, exceed 100 pounds, and the current snagging state record stands at 113 pounds and 4 ounces.

Today, the American paddlefish (Polyodon spathula) is the only remaining paddlefish species worldwide, and one of Nebraska’s most fascinating fish species.

A Natural History

American paddlefish are native to the Mississippi River basin, inhabiting large, free-flowing rivers, backwaters and oxbow lakes. They are extremely mobile, capable of moving thousands of miles between major river systems. In Nebraska, paddlefish are found in the mainstem Missouri River and the lower reaches of larger tributaries, including the Platte River, with the greatest numbers found in the lower unchannelized reach between Gavins Point Dam and Sioux City.

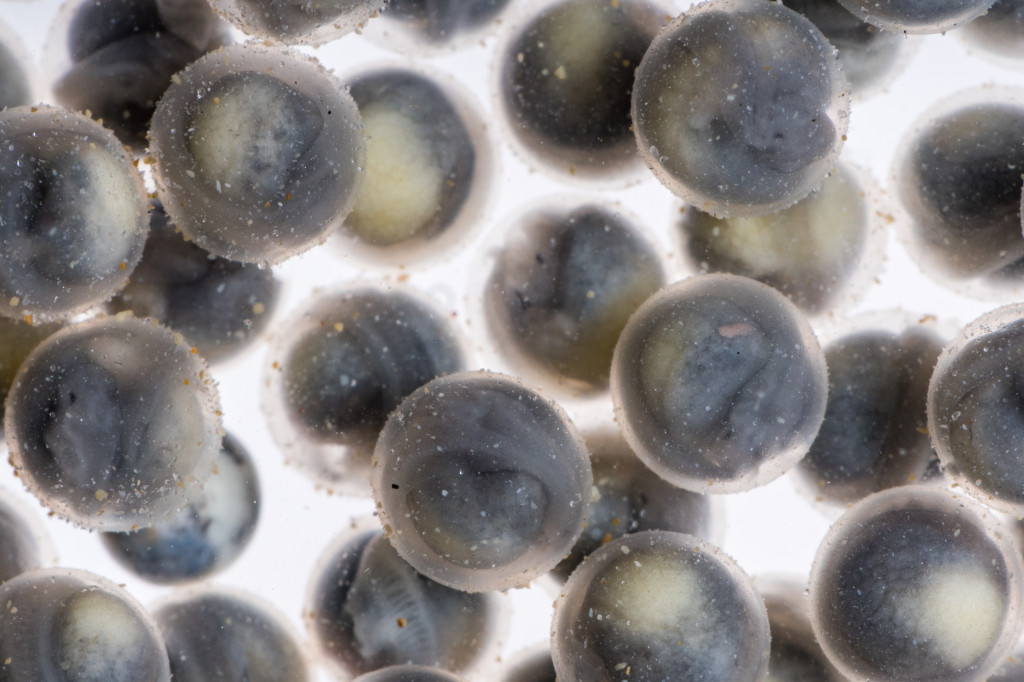

This highly sought-after fish is generally regarded as tasty among anglers, but commercial fishermen are mostly after the female’s eggs, or roe, which is processed into caviar. Paddlefish roe has become more desirable since the collapse of the Caspian Sea sturgeon market, primarily from beluga sturgeon (Huso huso) and other sturgeon, including the kaluga, Ossetra, sevruga, sterlet and Siberian sturgeons, and paddlefish fisheries. Labeled as American paddlefish caviar, the product can exceed $400 per pound. Although commercial fishing for paddlefish is illegal in Nebraska, the practice remains open in several other states. In our part of the Missouri River, management efforts have changed and evolved over the years, all in the hopes of protecting this unique fishery for future generations.

Fishery

The modifications to the mainstem Missouri River created the paddlefish fishery we have today. Construction of Gavins Point Dam was completed in 1955 and Fort Randall Dam in 1958. The construction of Fort Randall Dam, just north of the Nebraska-South Dakota border, formed a 39-mile riverine reach behind Lewis and Clark Lake that isolated this population from the open Missouri River. Below Gavins Point Dam, 811 river miles remain open, flowing into the middle Mississippi and connecting other large rivers. Although fish below Gavins Point Dam can swim unhindered, the dams created a barrier to upstream movement, causing populations to aggregate immediately below both dams, making them more susceptible to capture.

At the time, as expected, anglers quickly took advantage of the creation of this new fishing opportunity. These newly created tailwaters offered anglers a unique pursuit, different from the traditional sport fishing they were used to. Unfortunately, this unchecked enthusiasm caused overexploitation, and the paddlefish populations quickly suffered.

In 1959, anglers harvested an estimated 12,850 paddlefish below Fort Randall Dam, and three years later, only a few fish were harvested — indication of how sensitive this isolated population was between Fort Randall and Gavins Point dams. Because of this event, harvesting of paddlefish above Gavins Point was prohibited in 1987, and the regulation is still in effect to this day.

The reach below Gavins Point Dam remained open to fishing, however, as these mobile paddlefish populations were more resilient. Still, management actions had to be implemented to protect this fishery from exploitation. It has been an ongoing two-state effort.

Management

Since the closure of Gavins Point Dam and the inception of the fishery, the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission and the South Dakota Department of Game, Fish and Parks have jointly managed paddlefish. Over the next 30 years, daily bag limits and possession limits were adjusted, and the season length reduced.

In 1957, a two-fish limit and four-fish possession limit was applied, and in 1970, the limit was reduced to one fish and one in possession. The season length went from year-round to 212 days in 1974, to 151 days in 1983, and then to 30 days in 1987. Despite these management actions, anglers continued to harvest thousands of fish annually, and the fish they harvested were getting smaller and younger, suggesting the fishery was not self-sustaining. Consequently, a public meeting hosted by Nebraska and South Dakota biologists prior to the 1989 season informed anglers of declining harvest. Anglers, in turn, supported more restrictive management actions and agreed that the fishery needed to be managed to protect this unique fishing opportunity.

As a result of that public meeting, a derby fishery season was established prior to the 1989 season. It imposed a 1,600-paddlefish-harvest quota or 30-day-maximum, whichever came first, and no harvest outside of the snagging season. The harvest quota was based on a 5 percent take of the estimated population below Gavins Point Dam. Eager anglers rushed to the water, and the harvest quota was reached in just four days during that novel season. This derby-style fishery also caused safety concerns as high numbers of boaters and bank anglers created long wait lines at the creel station, boat ramps and limited parking areas.

The pressure on the paddlefish fishery remained high and monitoring was showing a population dominated by small, young fish with limited reproduction occurring. Therefore, prior to the 1992 season, the “slot” regulation was implemented, which protected 35- to 45-inch fish by making them catch-and-release only. Fish in this size range are the main breeders in a population, and the regulation made the fishery more sustainable. Additionally, a portion of the tailwaters was closed and hooks were limited to one-half inch in size from point to shank to reduce injury and mortality to fish that were caught and released. These management actions had little effect on harvest rates, and from 1993 to 1996, the harvest quota was still achieved in just a few days.

Following another public meeting in 1996, the limited-entry paddlefish snagging season was established. Each state issued 1,200 permits through a free-entry lottery system, and the season was moved to the month of October; furthermore, anglers could only snag between 7 a.m. and 7 p.m. each day.

The number of permits was increased to 1,400 in 2000 and to 1,600 in 2008 as annual harvest estimates were below the harvest objective. Due to the increasing number of anglers entering the permit lottery but not participating during the snagging season, Game and Parks began charging a $5 application fee in 2003. Prior to the 2007 season, the $5 application fee was waived and successful applicants purchased a permit ($20 for residents and $40 for non-residents).

The current permit structure was adopted in 2016, with a $7 application fee and permits costing $26 for residents and $50 for non-residents.

The present management objective remains at an annual harvest of 1,600 fish, 800 per state. Nebraska issues 1,600 snagging permits, expecting the success rate will be around 50 percent. Fisheries biologists from both states continue to work together to manage the fishery and the

harvest objectives.

Paddlefish snagging is a unique fishing opportunity, and recreational fishing is limited to a few Midwestern states: Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa, Kansas, Oklahoma and Missouri. Whether you’re interested in experiencing this unique fishing experience, enjoy eating paddlefish or spending outdoor time with family and friends, snagging is hard work, so be prepared if you ever decide to cast a line for paddlefish.

Kirk Steffensen is the Missouri River program manager for the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. He has worked on the Missouri River for more than 20 years.