Book review by Jeff Kurrus

Photos by Michael Forsberg

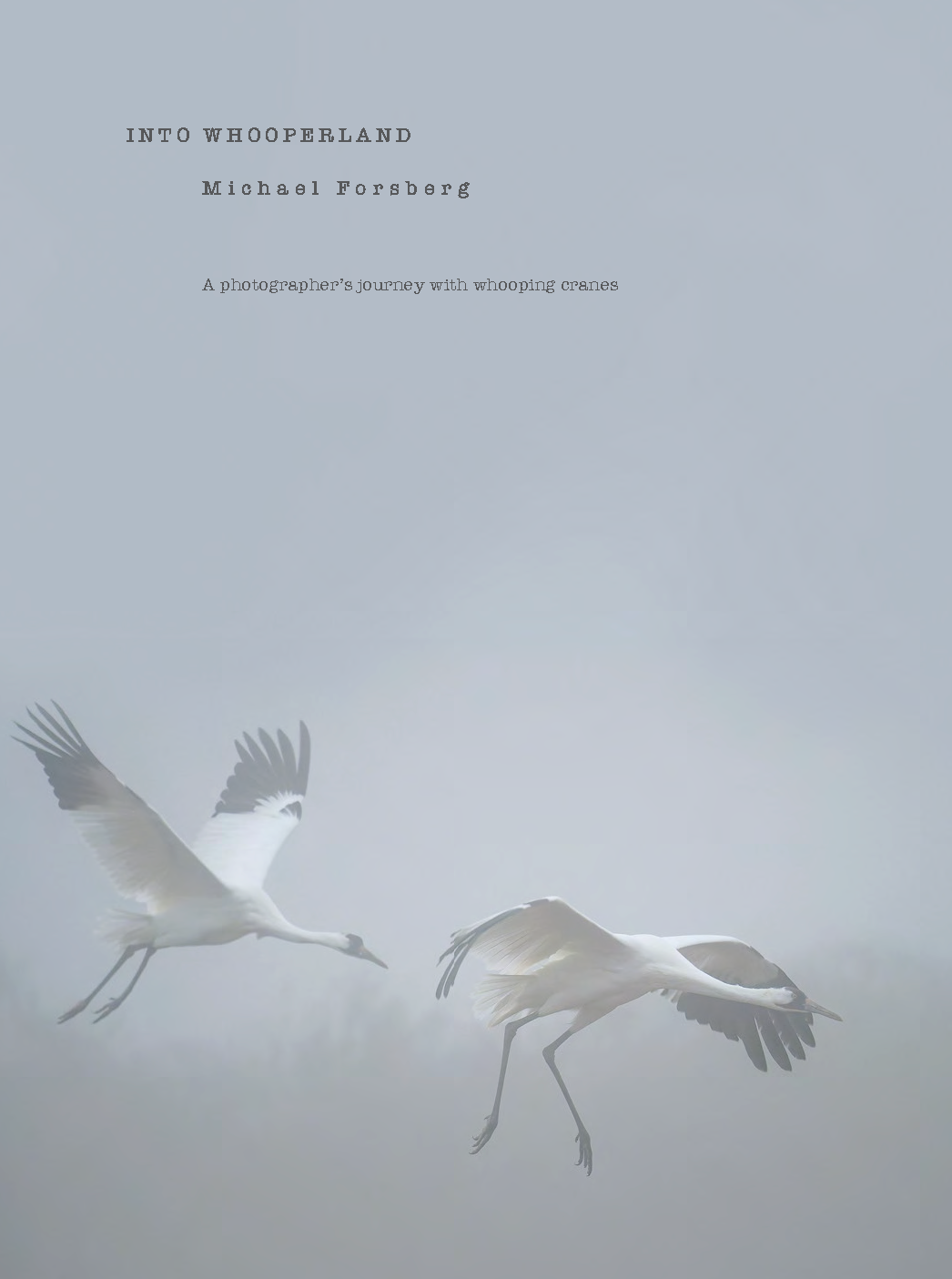

Michael Forsberg’s newest book, “Into Whooperland — A Photographer’s Journey with Whooping Cranes” is a celebration and warning to readers regarding one of the world’s rarest birds.

The book starts where Forsberg is at his best — in the field. A journal entry prepares readers for what is yet to come: “A flash of lightning from a predawn thunderstorm lit up the roost and revealed a glimpse of white among the thousands of dark shapes. As the storm passed and the veil of night lifted, there he was: a rare white wonder standing tall above the noisy pulsing masses of sandhill cranes.”

This description of seeing a lone whooping crane on the Platte River in Nebraska is indicative of this book’s most resonating strength: When Forsberg decides to tackle a subject, he is all-in. His work goes beyond photography, which is as stunning as it’s ever been.

To create “Into Whooperland,” he enlisted the help of what seems a countless list of scientists, landowners and other conservationists to deliver a simple message. This is written by Rich Beilfuss, President and CEO of the International Crane Foundation, in the book’s introduction: “We must find sustainable solutions for our lands and waters, for the wildlife we love and for our own livelihoods and future.”

This theme pervades throughout the book, the message hitting you on every page. Forsberg wants you to know that the world’s whooping crane population fell to fewer than 20 birds during the 1940s, and readers are reminded of this number across the book’s more than 220 pages. The story of the whooping crane is a warning of what has happened and what will happen if we don’t protect this bird — if we don’t protect all wildlife.

Another dedicated member of Forsberg’s team was Chris Boyer, who traveled with the author in a Cessna 1957 prop plane along Whooper Highway, the migration route from the Texas Gulf Coast to northern Canada. Or the International Crane Foundation’s co-founder George Archibald, known for “dancing” with captive cranes and encouraging Forsberg to write this book. Or scientist Andy Caven, who was his photo partner in the chapter entitled “Eight Days in a Blind,” where Forsberg chronicles his time in a photo blind deep in the heart of whooping crane nesting grounds in the boreal wetlands, forests and plains of Canada.

“One of us always watched the nest, except roughly between 11 p.m. and 2 a.m., when we both tried to sleep. The last thing I would do before nodding off was manually focus my lens on the nest. I kept a shutter release cable next to my head so I wouldn’t miss a photograph … .”

Drawings and other findings came from the trip. Observations became field notes and field notes became science. “Into Whooperland” provides insight into Forsberg’s many hours in a crane blind, and sometimes, in the most unexpected places, the reader finds humor. “The mosquitoes are fierce inside the blind this morning. Somewhere there is a breach.”

“Into Whooperland” is divided into the following sections, which read like chapters: “Winter Grounds,” “Migration North,” “Summer Nesting,” “Migration South,” “The Central Flyway” and “New Beginnings.” It is in the Central Flyway where Forsberg chronicles his trip with Boyer in the Cessna as he attempts to follow the whooping crane’s migration path through the heart of the continent.

The book is part love story, part coffee table book and all documentary. The reader learns that these birds mingle. They jostle. They most certainly dance.

The reader also learns all the difficult steps to rearing a chick in the wild and in captivity at the International Crane Foundation in Baraboo, Wisconsin, and how the population got so low in the first place.

“Whooping crane biology would have made them especially vulnerable to hunting and egg collection,” writes Beilfuss. “They are long-lived, become flightless when they molt their primary flight feathers every two to three years, reach breeding maturity at three to five years old, and raise one or (rarely) two chicks per year that require intensive parental care for about three months until fledgling … . The birds’ preference for breeding in wetlands of the fertile tallgrass and northern mixed-grass prairie regions, made them highly vulnerable to habitat loss as settlers plowed and drained those lands for farming.”

Alongside the book’s educational components are Forsberg’s images. Close-ups of whooping crane chicks and landscapes of nesting grounds. Workers in crane suits. Juveniles with their parents. Birds in Canada, Nebraska, Texas and parts in-between.

As a longtime contributor and former staffer for “Nebraskaland Magazine,” Forsberg is known for entrenching himself in his subjects — whether it be whooping cranes in his latest book or sandhill cranes in his first coffee table picture book — “On Ancient Wings.”

The book also contains a chapter entitled “Building the Backup Flock” by Rene Ebersole. This tells the fascinating story of Tex, Gee Whiz and Canus — three whooping cranes who have profoundly impacted the world’s current population of whooping cranes. Their story reminds readers of the human affects on these extraordinary birds and how science, love and common sense problem-solving have helped maintain this species.

Lastly, Forsberg shares a tip for the aspiring photographer: “I’ve found that the key to using blinds with cranes is to be in them before the birds arrive and to climb out of them only after they have left the area. It’s also necessary to live by the mantra of being comfortable with being uncomfortable. Blind work is a solitary experience. You must cope with being alone with your own thoughts, and often in physically awkward positions. Other challenges: weather extremes; myriad insects that buzz, bite and sting; knowing how to keep the blood flowing to your extremities at all times; and keeping your mind active. The moment you let your guard down is always when the action happens. Always.”

These words are a microcosm for handling difficult situations in conservation as a whole and for life in general.

This mindset has also allowed the population of one of the world’s rarest species that fell to fewer than 20 birds rise to roughly 830 known individuals today with names like Yay, Nay and even Husker Red.

Michael Forsberg’s “Into Whooperland” reminds us to not let our guard down.

“Into Whooperland — A Photographer’s Journey with Whooping Cranes” recently won the gold medal in the Nature category of the 2025 Independent Publisher Book Awards and is

available at MichaelForsberg.com.