By Eric Fowler

Dogged writer and photographer. Accuracy hound. Swearer. Whiskey drinker. That was Jon Farrar.

This colorful character of a man, who spent 42 years on the staff of Nebraskaland Magazine, passed away on March 30, 2021, at the age of 73. His closest friends will remember the stories he told, the late-night decoy carving sessions and how he disappeared into the Sandhills each October, primarily to hunt ducks. His body of work, however, including more than 580 articles, several books and tens of thousands of photographs honoring, and trying to conserve, the flora, fauna and history of our great state, will live on.

“He is Nebraskaland,” said longtime colleague and friend Michael Forsberg. “Not to take anything away from the others on the staff that were in that same generation, but he defined it. He set the bar.”

Nebraskaland employed writers and photographers when Farrar was hired, and he excelled at both. His other passion was research. He leaned on colleagues for insight and read everything he could find on a subject, from scholarly papers to first-hand accounts, before ever setting foot in the field. Once there, he recorded his own observations in field journals, a practice he began as a youth growing up a short walk from the Loup River in Monroe. Those small, brown, tattered notebooks came to be arranged neatly in a file cabinet in his office, to aid his own or a fellow staffer’s work long into the future. “As an outdoor writer I can think of few that were as good of a naturalist as him,” said Gerry Steinauer, a longtime colleague.

Farrar produced articles with a greater depth than had been seen previously in Nebraskaland, a depth that makes many of them reference material still today.

Often, his work focused on articles about little known species that could be considered obscure.

The Obscure

Farrar wrote many natural history pieces during his career, stories detailing the life cycle, habits and habitats of plants and mammals of the state. While he wrote several on common species, including pheasants, Canada geese and bald eagles, many of his subjects were species the magazine’s readers likely had never heard of, much less seen. There were stories on shrikes, skinks, wood rats, blue-eyed grass, and perhaps Farrar’s favorite, grebes.

In 1984, he wrote “Crested Hell Divers,” a story about eared grebes, one of three subspecies of the birds found in the state. It is perhaps the best collection of photographs he captured for a story.

“Jon didn’t just think those birds were cool, he was in love with those birds,” Forsberg said. “And every story that he ever wrote about them, that love was just sort of oozing from the page and from the pictures.”

That collection of eared grebe images provides a glimpse of the time Farrar spent in the field. He didn’t just take one trip, capture a few frames and call it good. He went back time and time again, brushing aside heat, cold and bugs, to get the images he needed to tell the story of the lives of these creatures.

He also cared about his subjects. When photographing nesting birds, he slowly moved blinds closer, often through the course of days, hoping they would accept his presence. In time, he knew which birds would and which ones would not. One bird he wrote about in “A Tale of Two Stilts” in June 2001, the black-necked stilt, never really did.

As Farrar chronicled, it was hot and there was no wind, and the stilts, one appearing to have “sheer terror in her eyes,” were taking turns tending the three chicks that had hatched that morning and one yet-to-hatch egg, between cooling off in the water. “The birds were suffering,” Farrar wrote. “I was torn between doing what was right, and what I had to do. I had nearly as many days invested in the nest as the stilts. And, if I left my grass-covered blind only 12 feet from the stilt nest, I might disrupt the hatching more than if I stayed. Telling myself that helped briefly. But I knew this was the most important day of the year for the two stilts panting and pacing near the nest. By noon, my conscience was unbearable. I pulled the blind and quickly left the meadow.”

Farrar focused on these lesser-known species partly because he hated the ordinary. But he also wrote about them in hopes of fostering greater appreciation among people for all things wild, and the landscapes and habitats in which they lived. To him, they mattered, just as much as the game species with which most people were familiar.

“He was way more interested in the true natives and the little guys, the underdogs … the kangaroo rats and blowout grass species,” said Jim Van Winkle, a long-time friend of Farrar’s from Wood Lake. “I think he felt that those species were entitled to recognition. And they were just such an intrinsic part of the ecosystems up here that they needed to get the same amount of attention that a ring-necked pheasant would.”

The Sandhills

Farrar’s true love was the Sandhills. He loved everything about the region, and in 1977, he produced an entire issue of the magazine dedicated to it. “Have you got a few minutes?” he wrote in this issue. “Have another cup of coffee and let me tell you what I know of these hills and their people. No, I’m not a sandhiller; didn’t even move here as a boy. But I wish I had. I’m just passing through, like you, but I’ve passed through here before and I know something of these people.”

He wrote about the history, from the Native Americans who lived there and passed through on hunts, to the French explorers, early cattlemen, homesteaders and ranchers. He wrote about the ecosystem and its origin, from the lakes and marshes and fens in the valleys to the grass covered dunes to the blowouts. He wrote about the fish and wildlife, and the opportunities they provided. And he wrote about the men and women who now live and work there.

He wrote stories about the black pioneers who homesteaded near Brownlee, about several ranches and the people who built them, and on the short-lived potash industry near Lakeside and Antioch.

“I think it was a combination of the people and the landscape,” said Joe Hyland, a former colleague and long-time friend. “He was fascinated by the people who lived that life in the Sandhills, both early and to this day.”

He would disappear for days in the Sandhills, far from the nearest highway and motel, living out of the back of his truck. In the fall, he hung his waders at several hunting base camps in the search for ducks, geese, grouse and pheasants. But his love for the obscure extended to the field, where his passion for hunting included snipe and diving ducks.

“He loved a lot of places in Nebraska,” Van Winkle said. “But he always told me this was his second home up here in the hills.”

History

True to his position, Farrar wrote about the history of hunting, fishing and boating in the state. He poured over columns by Sandy Griswold that ran in the Omaha Bee and World-Herald in the late 1800s and early 1900s to gain more insight on hunting, fishing and even wildlife populations.

He wrote about many old hunting clubs, including Ducklore Lodge on the North Platte River and The Merganzer Club near Cody, both run by brewers from Omaha. On his own time, he wrote a book on the Red Deer Club south of Valentine.

“He just spent an inordinate amount of time piecing together little details about all of these clubs that haven’t existed for years,” said Van Winkle. “He was a hound hunting for information on those old clubs.”

Farrar collected, built, and, of course, used decoys, so it’s no surprise that he wrote several pieces on the history of decoys, including Herter’s, Mason, paper, miniature, Nebraska-made and even live decoys.

For all of these pieces, Farrar talked to people who were part of the history. Lots of them. He tracked down old men who were market hunters, duck club members and ranchers. He would sit in their kitchens, or in some cases, their rooms at the local nursing home, turn on his cassette recorder, and listen to the stories of their lives and those who came before them. Sometimes he would go back for more.

Some believe that Farrar wrote some of these historical pieces because he felt that if he didn’t do it, no one would. “He knew it was getting away,” Van Winkle said. “Like we all know, we lament the things we didn’t do and the people we didn’t talk to and the records that we don’t have. He did something about it.”

Conservation Issues

Farrar took on many environmental issues, and others, in a tell-it-like-it-is style. His “A case for shelterbelts” in April 1971 bemoaned the fact that tree claims, planted by settlers to cut the wind on the prairie, were being bulldozed at an alarming rate. He pointed out the benefits, both economically, socially and for wildlife, debunked myths, and simply said: “If you have a shelterbelt — keep it. If you don’t — plant one.” The story could be run nearly verbatim and still apply today.

He wrote against channelization of the Missouri River between Yankton and Sioux City, a dam on the Niobrara River, the incursion of center-pivot irrigation systems into the Sandhills, and unethical hunters. He authored many lift-outs for the magazine that detailed some of the state’s most sensitive and imperiled lands, including wetlands in the Rainwater Basin and the rare saline wetlands near Lincoln, and the Platte River. He ruffled the feathers of many, including farmers, power companies, developers and sometimes readers with these works.

“I think what I liked most about Jon’s writing is he had really a unique way of describing or writing about environmental problems, and sort of putting the skewer in the sides of people who were not ethical and really didn’t care about wildlife,” long-time colleague Carl Wolfe said.

Joe Hyland appreciated “Sky Carp,” a piece Farrar did in 2001 on snow geese after seasons were liberalized in an attempt to reduce the population of the bird, which was so high it was destroying its own nesting grounds in the Arctic.

In it, Farrar detailed nearly every attempt he made to capture magazine-worthy photographs of the bird throughout his career, the behaviors he witnessed, what he learned from them, and how he appreciated them. “He kind of took the people who look down their nose to snow geese to task,” Hyland said. “Jon never treated them irreverently. He didn’t like people calling them sky carp. They deserved better than that.”

Knock Their Socks Off

Farrar was a great storyteller with a great sense of humor. Who else would, during his younger days, keep a small rattlesnake in a coffee can in his office for when visitors entered? Or walk in front of a colleague’s middle-of-Nebraska-nowhere trail camera and make obscene gestures toward the lens?

His ability to tell a story extended to his work. He was a master with the keyboard and the camera. “His work is the standard by which everything else can be measured,” said Forsberg.

A few years before his passing, he bestowed this advice on me. “Grind out the stuff you need to do to buy groceries, but once or twice a year knock their socks off. When you look back, should you live so long, those will be the ones you’re glad you did. The ones that last — that some snot-nosed kid will quote in his Ph.D. dissertation 50 years from now. Yeah, I know, you’re dead and won’t know, but it would be good now if you saw you were doing something significant in the long-haul.”

That was Jon Farrar. ■

“To be in a marsh. The rich, stagnant fragrance of marsh. The gray sky. Drizzle on the neck. Squads of snow geese and courtship flights of pintails. The scene cries out for description, yet defies it. A glimpse back to our origins, a closeness to life other than our own, as if we belonged somewhere, finally belong somewhere … .”

– Jon Farrar, from “Sky Carp”

copy

Subheads are H3

A Love of Wildflowers

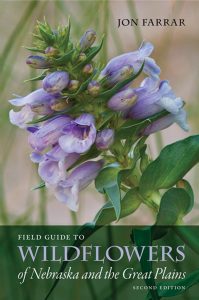

Jon Farrar approached his Field Guide to Wildflowers of Nebraska and the Great Plains, originally published in 1990 with a second edition in 2011, with the same conviction and care for the species as the rest of his projects.

“There is no way I could pick just one wildflower as a favorite,” he wrote. “Each is special in its own way, especially when you consider how it evolved to prosper in its own niche in the world.”