By Monica Macoubrie, Wildlife Education Specialist

Picture this: You’re fishing on the Missouri River and all a sudden, you feel your line tug hard! You have a huge fish ready to pull you in — a real monster at the end of your line. Your adrenaline is going, and as you reel in the fish, you start to see its tail emerging from the water. You see rows of scales and a shovel-like nose.

“What in the world is this?!”

You finally pull the fish up to shore and realize it is a dinosaur. Okay, not really a dinosaur, but it might as well be. Before you is a sturgeon, one of the most ancient groups of fish you could have found at the end of your line.

Sturgeon are true living fossils, as they haven’t changed much over thousands of years. Let’s travel back in time and take a closer look at these native and truly unique fish found in Nebraska.

Sturgeon Family Traits

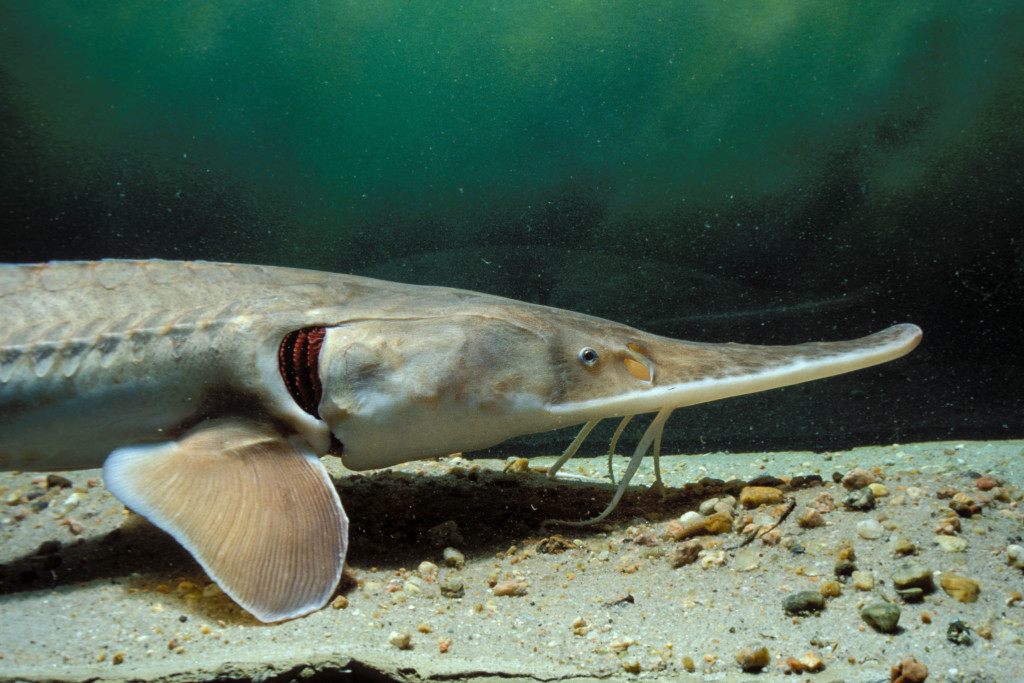

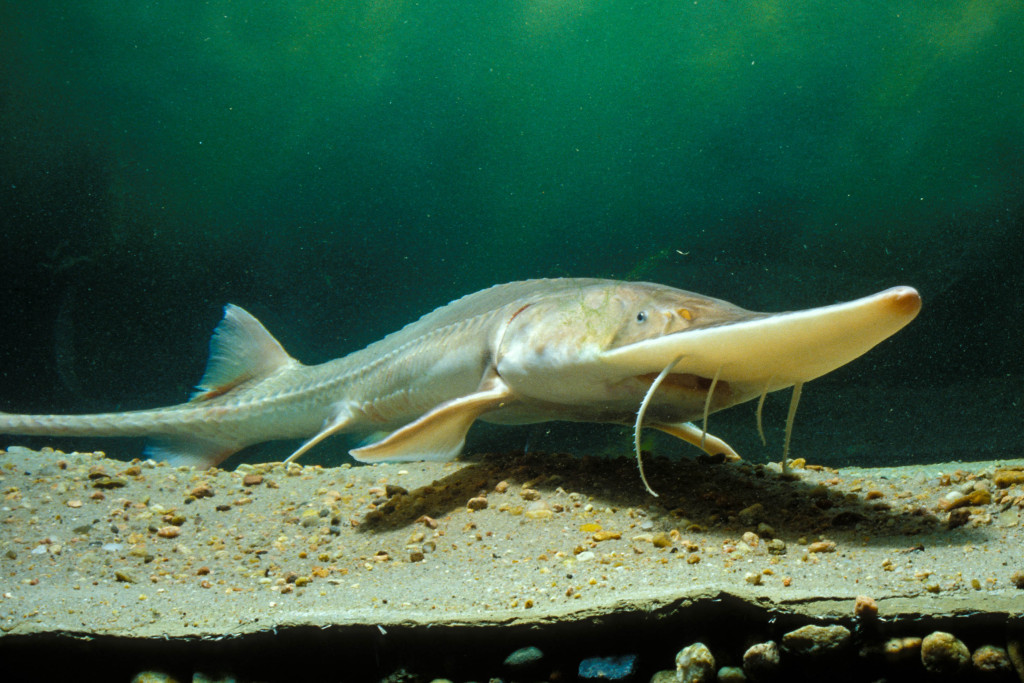

Sturgeon are in the Acipenseridae family, which globally houses around 25 species of large primitive fish. Fish in this family are technically known as bony fishes, but their skeleton is largely made of cartilage. Other features common in this family of fish are elongated bodies; rows of bony scutes, or plates on the body; barbels, which are whisker-like projections in the front of the mouth; and a protrusible, vacuum-like mouth. Some species in the world can reach great size and age. Specimens over 18 feet have been found in the wild and calculated at more than 100 years old.

The name sturgeon in European languages translates to “the stirrer,” on account of the fish using their barbels, located on the underside of their mouth, to direct food into it. One characteristic feature of sturgeon is their toothless, protrusible mouth, which extends in and out to vacuum aquatic insects, mussels, worms and crustaceans off the river floor. They are what scientists call opportunistic feeders and will pretty much eat anything they can suck up. When the barbels find food, the protrusbile mouth will drop down and rapidly suck in the meal. Sturgeon are one of the few fishes that have taste buds on the outside of the mouth, which is helpful for food selection; normally, the taste buds on fish are found on the tongue or the inside of the mouth.

Acipenseridae is one of the oldest families of bony fish in existence and sturgeons are one of the few vertebrate taxa that retains a notochord into adulthood. A notochord is a skeletal rod that supports the body. Most animals have this rod in the embryonic stage, but lose it as they grow into adults – sturgeons retain it. Out of the roughly 25 species that are found globally, Nebraska is lucky to be home to three of those species: the shovelnose sturgeon, the lake sturgeon and the pallid sturgeon.

Shovelnose Sturgeon

The shovelnose sturgeon is the smallest of the ancient sturgeon species found in North America. They get their name due to their flat, shovel-shaped snout. This sturgeon species is often a dark tan to gray color, or sometimes even a yellow-ish green or pink in Nebraska, and they rarely exceed five pounds in size. Shovelnose juveniles have a long filamentous tail that normally breaks off as the fish ages, although sometimes it is retained. This fish can be found in murky environments, such as the Missouri River. They favor strong currents and deep channels of larger rivers where there is a sand and or gravel bottom.

Spawning season for the shovelnose is usually April through early July. During this time, the fish will swim closer to the surface to search for mates. Being a relatively long-lived fish, sexual maturity in this species, like many other sturgeon species, is relatively long. On average, it takes around 5 years until males become sexually mature, whereas females don’t mature until around 7 years of age.

Shovelnose sturgeon are known to hybridize with the larger pallid sturgeon. Changes to the river have forced these two species to share spawning sites. Historically, shovelnose sturgeon were found throughout most of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers from Montana to southern Louisiana. Today, channelization and the construction of dams and navigation locks has led to significant decline to the fish’s ancient spawning grounds.

Lake Sturgeon

Lake sturgeon are the largest of the sturgeon species in Nebraska and the rarest. Like other sturgeon species, they have an elongated body. The coloration of this fish is highly variable, but most typically, they are dark brown, pale brown, slate gray and even sometimes black, although that is rare. Juvenile lake sturgeon have large black saddle marks that are peppered with small black spots that disappear as they mature. Their rostrum, or nose, is longer in adults that in juveniles and is slightly upturned compared to the pallid sturgeon and the shovelnose sturgeon. It is common for this fish to reach around 6-8 feet in length and weigh 200-300 pounds.

Spawning for this species takes place from late April to late June. Lake sturgeon take an extremely long time to mature: nearly 15 years in males and as long as 26 years in females! Females also only spawn in the wild every 3-6 years — it is no wonder this species has trouble increasing its population. When females do lay eggs, they lay on average 2-3 million eggs at a time; the number of eggs will depend on the health, age and size of the female laying them. Sturgeon eggs are small and sticky and encased in a jelly-like substance – true of all sturgeon species. This substance help them adhere to water plants and stones.

The lake sturgeon is listed as either a threatened or endangered species in 19 of the 20 states within its original range in the U.S. In Nebraska, it is listed as a threatened species. Non-native fish, less moving water and changes in the river flow have all contributed to the decline of this species as well as the food it depends on. Many of these fish struggle to find a mate. Fish that are reproductively mature today were all spawned before the construction of dam systems and are nearing the end of their lifespans.

Pallid Sturgeon

When scientists talk about living fossils, the pallid sturgeon of Nebraska truly fits this description with its dinosaur-like appearance. This is one of the largest freshwater fish in North America. Pallids can range from 30-60 inches in length and can weigh just shy of 100 pounds. This sturgeon is distinguishable by its pale coloration, and as these fish age, they turn bright white or extremely light gray. Juveniles, however, are easily confused with shovelnose sturgeon as they are the same color until they start maturing. Another distinguishing feature is the pallid’s heterocercal tails. This simply means that their top fin is longer than the bottom fin. Shovelnose sturgeon have this as well, however, it is much more pronounced in the pallid sturgeon.

When flipped over and viewed from the bottom, the pallid sturgeon has four barbels with the outer pair twice as long as the inner pair. This is unique among pallid sturgeon.

Just like other long-lived species of fish, pallids will not reach sexual maturity until 7-9 years for males and 9-15 years for females. Males generally spawn every 2-3 years and females tend to spawn on a 3- to 5-year cycle. Reproductive pallids will start to move upstream beginning in the late fall and spawn in the spring and early summer, March through June. They spawn over gravel beds or other hard-bottomed surfaces. These fish can live to be 50 and perhaps even as old as 100 years.

Little is known about the eating habits of this species. Scientists think they are most likely opportunistic feeders. However, some studies have shown that they could have seasonally-dependent diets. But, like other sturgeon species in Nebraska, they are generally bottom feeders and will use their protrusible mouths to suck up small fish, mollusks and other food sources from the river bottom.

The pallid sturgeon was listed as a federally endangered species in 1990 due to extensive habitat modification, lack of reproduction, commercial harvest and hybridization with shovelnose sturgeon. Recovery efforts by many state wildlife agencies, including the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, include strategies such as protection from harvest, protection of habitat and stocking of hatchery-raised fish. These efforts have also been extended to include research and monitoring studies critical to the reproduction and spawning of these ancient fish.

If you catch a suspected pallid sturgeon, you must quickly and carefully release it back into the water.