By Gerry Steinauer, Botanist

The prairie coneflower and pale purple coneflower are native perennials that grow in dry to moist prairies in Nebraska, while the non-native purple coneflower is commonly planted in flower gardens and prairie restorations. In early summer, each coneflower stem develops a single flower head with a ring of pink to rose-red, spreading to drooping petals.

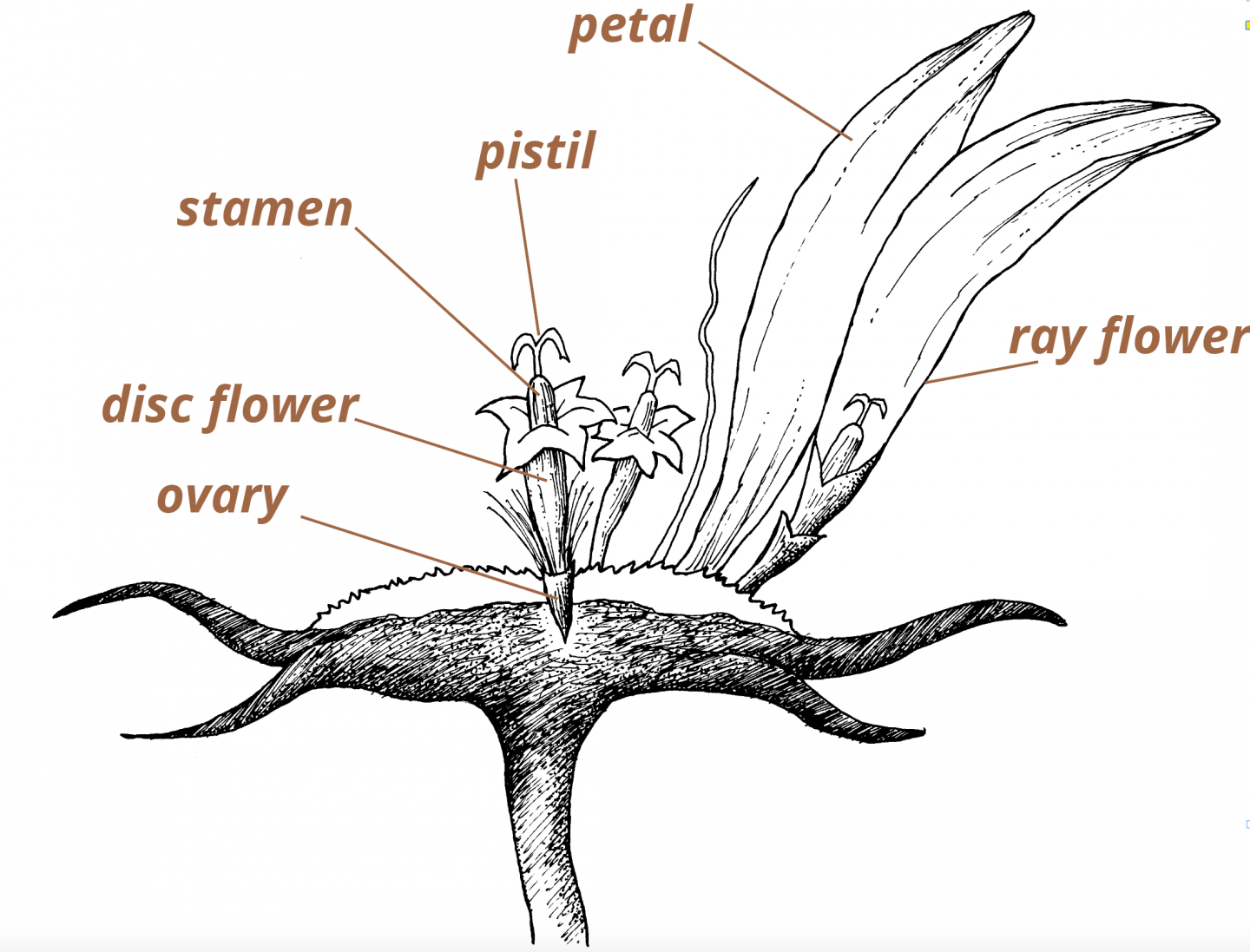

Like most wildflowers, the coneflowers’ showy, colorful blooms are designed to attract pollinators, mainly butterflies and bees. However, these plants, along with other members of the sunflower family, use a bit of trickery. What looks like a single large flower is actually a cluster of many small flowers, arranged to mimic one big bloom.

About 60 to 70 million years ago, when sunflowers first appeared on Earth, their flowers were small and drab. Back then, their pollen was carried between plants by the wind, so there was no need for nectar or bright colors to attract pollinators. But as insects diversified and more became pollinators, it became more efficient for the plants to rely on them instead of the whimsies of the wind. This shift led to more seeds and better survival.

To attract pollinators, coneflowers adapted by arranging their small flowers into a domed, reddish-brown disc, with those in the outer ring developing petals. The tubular, petal-less disc flowers contain both male, pollen-producing stamens and a female pistil that produces a seed. Surrounding them, the ray flowers — those with petals — are sterile, serving only to attract butterflies and bees.

The continued survival of coneflowers shows that deception has its rewards.