By History Nebraska

Nebraska’s early roads were unmarked trails across the countryside. Railroads received large government subsidies, but the dirt roads linking farms and towns were seen only as a local concern.

Most people assume a marked effort to improve roads at the local level came about because of automobiles. That’s partly true, but the nationwide “Good Roads” movement started years earlier. It began with bicyclists.

The invention of the modern “safety bicycle” led to a nationwide bicycling craze in the 1880s and 1890s. The new bikes were safer and easier to ride than their high-wheeled predecessors. Nebraskans formed bicycle clubs and explored the countryside. Some men and women completed “century rides” of 100 miles in a day. (Imagine doing that on dirt roads on a heavy, single-speed bike. And women did this in long skirts!)

At the time, Nebraska’s larger cities were beginning to pave their main streets. In rural areas, roads were bare dirt – not even graveled. Bicyclists soon found allies among farmers and small town merchants who wanted better farm-to-market roads.

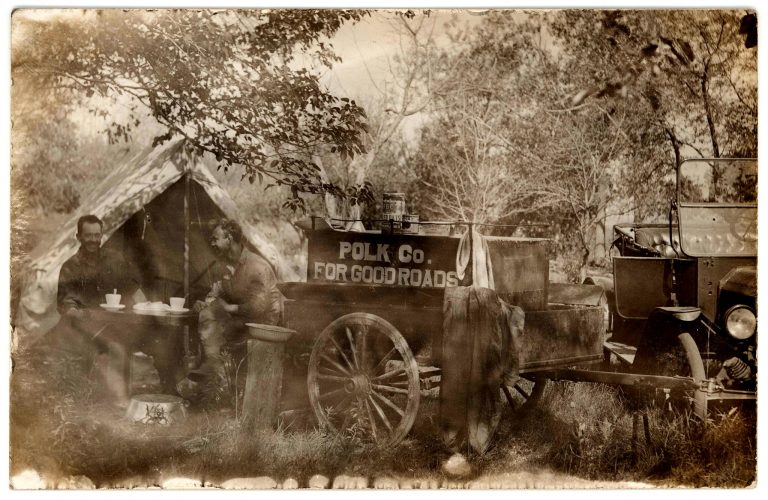

Many Nebraska towns had commercial clubs to promote local business. Some of these clubs formed Good Roads committees to raise funds for road equipment. They sponsored road building “bees” in which rural and town volunteers labored on sections of roads. Even dirt roads could be improved by grading or by being dragged with heavy split logs to smooth the surface.

The Good Roads Movement gained momentum with the coming of the automobile. City drivers on country roads infuriated farmers by scattering their chickens, frightening their horses, raising plumes of dust, and damaging roads that were often maintained by the farmers themselves.

But as autos became more affordable (starting with the Ford Model T in 1908), farmers began modifying cars into early pickup trucks. “If anyone on earth needs the motor car, it is the farmer,” said the Nebraska Farm Journal in 1911.

Even before paved roads were common, road maintenance was too big a project for local volunteers or county employees. Motorists began calling for state and even federal funding of roads. It took decades of promotion to convince enough voters and lawmakers that this was a good idea. Nobody wanted their taxes to go up. Most roads long remained unimproved as a result.

The bicycle craze faded, but automobiles grew more popular year by year. In 1916, the number of cars registered in Nebraska topped 100,000. By then, local groups were working with multi-state organizations to promote “automobile trails” – the beginnings of the modern highway system. Roads such as the Lincoln Highway (more-or-less the future U.S. Highway 30), the Detroit-Lincoln-Denver or D-L-D Highway (U.S. 6), the Meridian Road (U.S. 81), and dozens of others were cobbled together from existing local routes, marked by painting telephone poles, and promoted through maps and guidebooks. Here’s how the Automobile Blue Book described a section of the Meridian Road between Norfolk and Pierce in 1912:

“Turn left from business center and at the fork … bear left, following the angling road straight out of city through edge of Hadar … bearing right with road … Jog left and take first right. Turn left 1 mile, then right ½ mile. Turn left 1 mile into Pierce.”

Later, concrete markers were added to guide adventurous motorists. Sharp-eyed travelers can still spot some of these markers along backroads around the state.

The federal system of numbered highways was adopted in 1925, transforming the old automobile trails into U.S. highways. That year, Nebraska adopted a gasoline tax to raise money for roads. Auto travel gradually became less of an adventure, but faster and more reliable.

Adapted from “The Good Roads Movement in Nebraska” by L. Robert Puschendorf, from the Winter 2015 issue of Nebraska History. Visit History Nebraska’s website at history.nebraska.gov.