By Mariah Lundgren

There is a type of wetland found in the Nebraska Sandhills that holds mystery and wonder — fens. Unique and rare plant species make their home in this boggy and bouncy land. Formed over thousands of years, fens are an important part of our natural history and are critical in cleaning our air and water. But first, what makes a fen a wetland?

What Are Wetlands?

Wetlands are defined by the presence of water, water-loving plants and soils that have been developed in wet conditions. Wetlands in the Sandhills are found where the Ogallala Aquifer meets the surface in the valleys and between the hills, along the shorelines of the many rivers and streams, and on the edges of lakes. Impressively, the Sandhills are 20,000 square miles, have more than 1 million acres of wetlands and are one of the last truly wild landscapes left in the Great Plains.

The Sandhills are the most intact temperate grassland left in the world and have remained relatively undeveloped since the westward movement of European-American settlers. The sandy, porous soils make row crop agriculture challenging, unlike much of the Great Plains, which has been turned to the plow. However, with renewable energy development, such as wind, encroachment of woody vegetation and the wealth of groundwater that lies beneath, threats loom on the horizon.

Fens

In spring 2021, Platte Basin Timelapse producers Ethan Freese, Dakota Altman and I spent three days with Nebraska state botanist Gerry Steinauer and Nebraska wetland program manager Ted LaGrange. The itinerary of this trip was to explore three fens on public and private lands deep in the heart of the Sandhills. So naturally, this trip coined the name Fen Fest.

A fen is a type of wetland that is perpetually fed by cold groundwater. Its soils are saturated, and they form in low oxygen conditions, otherwise known as anaerobic conditions, over a long period of time. The cold and wet conditions drastically slows down plant decomposition, and the partly digested plant matter found in fens turns into a type of soil we call “peat” and “muck.”

Fens are found in various climates, including warmer and arid regions, such as the Sandhills of Nebraska. If you see a fen from the side of the road, you would hardly know it. However, when you set foot on one, it will feel like standing on a waterbed in places. This is due to the bouncy nature of the peat and muck soils and their proximity to groundwater. Fen ecology is fascinating and supports a diversity of plant and animal life. Scientists and researchers are still learning about how these unique ecosystems function.

Legend has it that cows, cars and tractors have been swallowed by fens. During a later excursion, that legend became fact.

Fen Fest

The three fens we visited during Fen Fest were located on the banks of Steverson Lake at Cottonwood-Steverson Wildlife Management Area on private land owned by the Ravenscroft family and on the Turner Enterprise’s Spikebox Ranch. As guides, Gerry’s and Ted’s combined knowledge made for a fun and informative experience.

My favorite fen was on John Ravencroft’s ranch. His ranch is deep into the rolling Sandhills, where dark skies are prominent and wetlands and grasslands flourish. We joined John, his wife and son on a tour out to the fen, and we watched them walk out onto the springy mat of peat and bounce around, giddy as ever. Gerry then pointed out a plant species, marsh marigold, which typically prefers cooler and wetter climates. The microclimate found within the fen makes an ideal habitat for this species and many others, such as bog bean, cottongrass and Nebraska sedge. We ended the excursion back at the Ravencrofts’ home, where they delighted us with mint chocolate chip ice cream, homemade brownies and warm conversation.

Fen Fest: Part 2

This past fall, the same team, minus Gerry, plus others from Nebraska Game and Parks and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, visited a fen in the far eastern Nebraska Sandhills, where we installed a PBT timelapse camera to watch the fen wetland change over time. Naturally, we called this outing Fen Fest: Part 2, which I am hopeful will become a new tradition with our group.

It was a windless evening — the air was crisp, and the temperature was pleasant. Our mission was simple: to explore the fen and swap memory cards on the timelapse camera. However, when we arrived at the spring, we discovered something not quite right. A cow bone was found in front of the camera right next to the spring.

“Hmmmm,” Dakota said. “This was not here last time we checked the camera.”

That led us to think either A) the cow bone was brought here by another animal, or B) the cow was swallowed by the fen. We quickly moved on from the cow bone and began exploring the bottomless springs, charming plant life and each other’s company.

A few weeks later, Dakota downloaded the images from the timelapse camera, and lo and behold, the timelapse recorded a calf getting stuck in the spring that fed the fen, dying and decomposing. [See photos below.] So, it turns out that the legend of cows being swallowed by fens holds true, and now this cow will be part of the fen forever. However, there is no need for humans to fear fens, as we are not aware of any people getting stuck in them.

Beyond the ecosystem benefits these fen wetlands provide, they are also connectors. Fens bring people together. They are places to enjoy the wonder and surprising beauty of an unassuming, overlooked landscape. They take us back to our playful, childlike state and make us forget the troubles in the world. I hope more people will learn about them and understand that we need places like fens to stick around forever.

Wetlands of Nebraska project – For more information about fens and all types of Nebraska wetlands, visit nebraskawetlands.com. See timelapse footage at plattebasintimelapse.com.

Anatomy of a Sandhills Fen

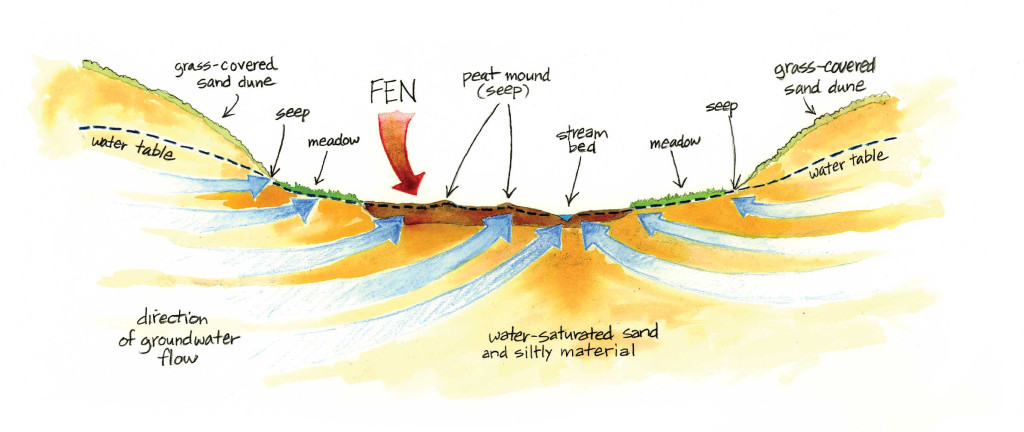

Some groundwater under dunes moves laterally, surfacing as seeps low on hillsides at the edges of valleys and in the valley floor. Where the cool groundwater has flowed to the surface for hundreds or thousands of years, the decomposition of plant material is slowed and deposits of peat have formed, some 22 feet thick. In some parts of fens, where groundwater wells to the surface, the rate of decomposition is even slower and mounds of peat rise as much as 8 feet above the surface of the fen.

Cow-swallowing Fen

Connected to the storied prehistoric past and an ever-evolving future, Jenning’s Fen is a unique wetland ecosystem found along the easternmost edge of the Sandhills and connects to a shallow meandering prairie river called Beaver Creek. Fens are where ancient groundwater pushes up to the surface, supplying cold water that supports a plant community that has persisted since the ice age. Plants such as bog bean, marsh marigold, marsh fern and the rare Loesel’s twayblade orchid can be found in fens. This timelapse camera looks into two circular springs where sand and cool water boil to the surface, surrounded by a working landscape of cattle and ranching.