By David L. Bristow, History Nebraska

Building sod houses, especially when the wind blows, is not quite as pleasant as being out buggy riding with a girl,” wrote 20-year-old Swedish immigrant Rolf Johnson in 1876. “One’s nose, eyes, mouth, ears and hair gets full of loose dirt. OK! It’s bad!”

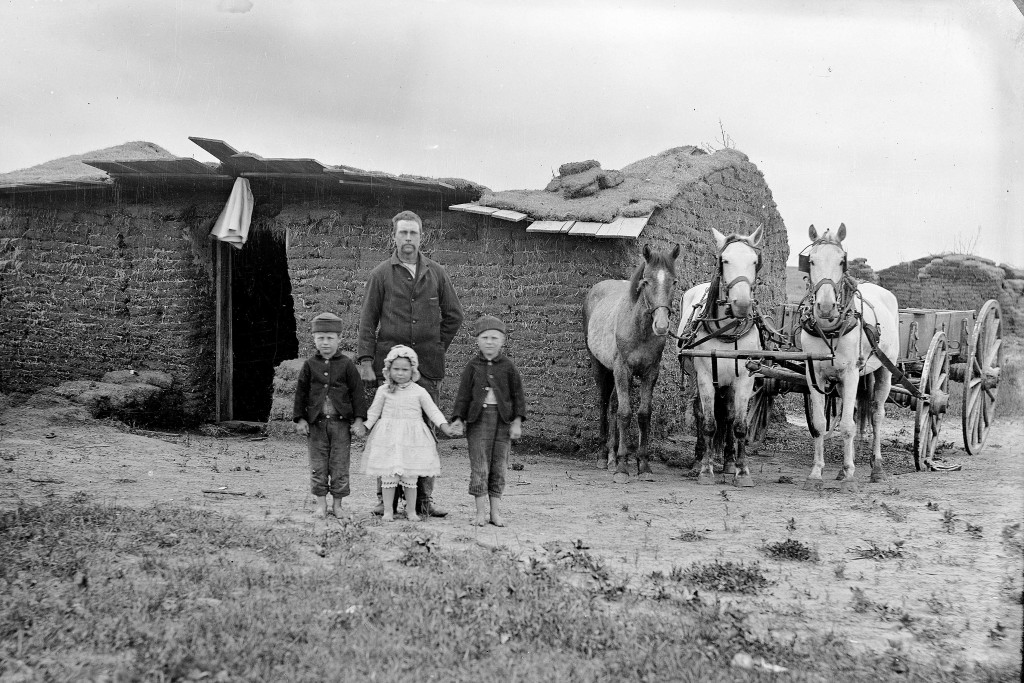

Living in Phelps County, young Rolf was learning soddie-building skills shared by many Nebraskans of his era. They all faced a similar challenge — how do you build a home in a place with few trees, and where imported lumber is either unavailable or too expensive?

As with the earth lodges of Native peoples such as the Pawnee, sod houses were a clever adaptation to local conditions. Building one required not only a lot of hard work, but also planning, skill and neighborly cooperation.

First, you had to find good sod from which to cut bricks. A sod house may look like it’s made of dirt, but each brick is held together by a tough, dense network of prairie grass roots binding the soil. The savvy home builder searched bottomlands near the water table for places where the roots grew together in a mat. Roots were toughest in fall, but builders rarely had the luxury of choosing the season.

Cutting sod required a team and a plow. It was best to use a “cutting” or “grasshopper” plow that turned the sod over in a long, neat ribbon that could then be cut into bricks. Plowing virgin sod was hard work — people spoke of the tearing sound the plow made as it sliced through the roots. It took about an acre of sod to build a 12-by-14-foot house.

Rolf Johnson told of cutting bricks that were “2 feet long, 12 inches wide and 4 inches thick,” which were then hauled to the construction site. Putting up walls required at least two men, so it was common for neighbors to help each other. Bricks were laid grass-side down so each layer could be trimmed level.

Walls were usually two or three sods thick, staggered like regular bricks (but without mortar), and every third or fourth layer was laid crosswise to hold the wall together. Door and window frames were held in place with wooden rods and topped with long cedar poles to spread the weight and keep the frames from buckling.

As the walls grew higher, the women shaved the interior walls with a spade to keep them balanced and to close any holes. (Interior walls were usually plastered as well.) Men used a wagon as a platform from which to lay the upper layers.

After reinforcing the base with planks, sod or even concrete, it was time to build the roof — the most important part. “If the roof failed, the house failed, for the endurance of the walls depended ultimately on the protection of the roof,” writes Roger Welsch in his book Sod Walls. While some builders could afford shingled roofs, most soddies relied on a sod roof.

A sod roof had the advantages of being cheap, a good insulator and relatively fireproof. And it would keep you dry in the hardest rainstorm … for a couple of hours. Then it would drip for two or three days after the rain ended.

A good ridgepole was crucial — or better, several good ridgepoles to distribute the weight. Heavy cedar beams were excellent if you could find them, but lifting them into place was difficult for a team of two or three men. The usual method was to lay two poles against the eave wall and use ropes to roll the beams into place. A combination of poles, brush, hay and earth completed the roof.

Most families moved out of their soddies as soon as they could afford a more spacious frame house. The sod house was then repurposed as a farm building. Some are still standing to this day.

Visit History Nebraska’s website at history.nebraska.gov.