By David L. Bristow, History Nebraska

Longtime Fort Robinson Museum curator Tom Buecker used to say that the most common question he heard was, “Where’s the fort?” Visitors expect to see a stockade, but like most Great Plains forts of its era, Fort Robinson was built without outer walls. It started as a tent camp 150 years ago and grew to become one of the largest military installations on the northern Plains.

The Army sent more than 900 soldiers from Fort Laramie to northwestern Nebraska in March 1874. Their tent camp was soon named in honor of Lt. Levi Robinson, who had been killed earlier that year by Native Americans from nearby Red Cloud Agency. The first post commander was Captain Arthur MacArthur — the father of Gen. Douglas MacArthur of World War II fame.

The soldiers had come to protect Red Cloud Agency, where the U.S. government distributed annuity goods to Lakotas in fulfillment of an earlier treaty. Tensions were mounting as Lakotas resented continued encroachments into their territory.

And things were about to get a lot worse. Later that year, Lt. Col. George Custer led an expedition that confirmed rumors of gold in the nearby Black Hills. When the Lakotas refused to sell the land, the U.S. launched what became known as the Great Sioux War of 1876. The famous Lakota war leader Crazy Horse surrendered his band of followers at Camp Robinson in May 1877. In September, Crazy Horse was killed while trying to avoid being imprisoned in the camp’s guardhouse.

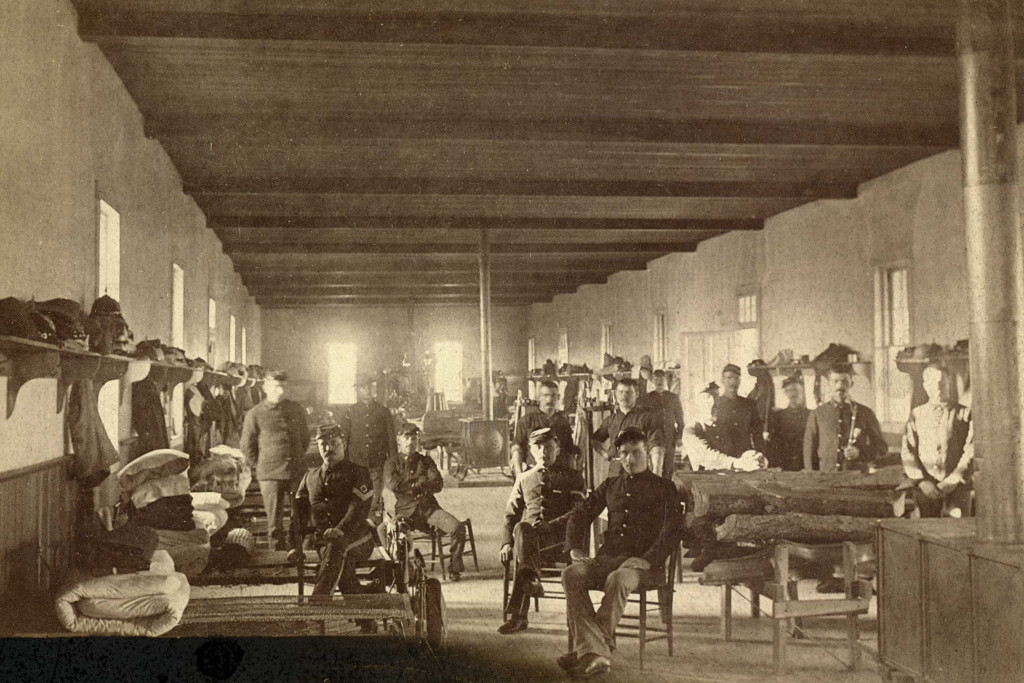

The following year saw another tragedy at the post, this time involving a group of Northern Cheyenne who had escaped from their reservation in Indian Territory (Oklahoma) and were trying to return to their homeland in present-day Montana. The army captured Chief Dull Knife and 149 of his followers and locked them in a barracks without food or fuel, hoping to pressure them to agree to go back to the reservation.

On the night of Jan. 9, 1879, the Cheyennes broke out of the barracks and, using weapons they had hidden, shot the guards and held off the other soldiers in a running fight known as the Cheyenne Breakout. Most of the Cheyennes were recaptured or killed.

While some of the buildings from that early era remain, others — such as the guardhouse and the Cheyenne Breakout barracks — have been reconstructed on site based on archeological excavations. Today, it’s common to see bundles of sage left by Lakota visitors on the Crazy Horse marker in front of the guardhouse. And every January, the Northern Cheyenne hold a ceremony at the Fort to honor their ancestors.

These stories and photos provide a glimpse of the Fort’s earliest years, but barely scratch the surface of its long history. Fort Robinson was home to African American “Buffalo Soldier” regiments in the 1880s and 1890s, trained cavalry horses as an Army Remount Depot following World War I, and became a prisoner of war camp and war dog training center in World War II. Today, Fort Robinson is a popular state historical park where visitors enjoy the outdoors while experiencing many layers of the past.

Visit History Nebraska’s website at history.nebraska.gov.