By Grace Gaard

I remember driving through a great expanse of shortgrass prairie on my way to visit Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, my husband in the driver’s seat. As far as my eyes could see, there was only the gentle curve of the landscape in sharp contrast with the sky — blue and pale. Miles passed and the wide, rolling landscape spread around me. Suddenly, a single tan and cream shape appeared. A pronghorn stood proudly, gazing across the sandy short grass under the bright sunshine.

No other beings breached the surface of the horizon that stretched out beyond the road. We passed it in a flash. I figured I would be able to keep my gaze on it for a while, with so little else to see. But in the time it took for me to glance forward and then turn around to look, this prairie phantom had disappeared. Gone without a trace. Where could it have gone in such a lonely landscape? Maybe it was the short shifting dunes as the car soared along. Perhaps there was more topography out there than I could see from my vantage point. But the feeling that pronghorn left behind only made me love this mysterious creature more.

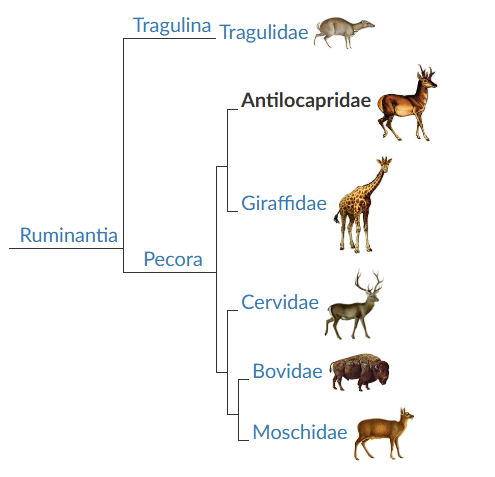

The pronghorn’s endurance and speed has carried it through centuries of change. Its ancestry traces back millions of years to Europe and Africa before the severed connection of our continents, and with the formation of mountains, the ancient Antilocapra americana was left to adapt in the western part of North America, while the remaining prehistoric members of its species vanished into extinction. The once large zoological family of Antilocapridae which roughly translates to “goat-like antelopes,” has just one unique member today: the pronghorn.

In an unexpected twist of events, the pronghorn is actually more closely related to giraffes and okapis of the family Giraffidae than any other living species. This fairly new discovery is based on a 2019 study of genome sequencing in certain ruminants. Though pronghorn may appear more similar to other species, research has shown that they are not deer, they are not goats, and they are not antelope.

Pronghorn, Not Antelope

The pronghorn’s body is a puzzle of adaptations that have allowed them to maintain their title as North America’s fastest land animal. At their swiftest, they reach speeds between 50 and 60 miles per hour.

What primarily sets the pronghorn apart is their possession of forked horns which are covered in a sheath of keratin. Keratin is a fibrous protein that makes up a large part of hooves, horns, feathers, scales, skin, hair and nails. Bison and bighorn sheep also possess keratinous horns, but those remain on their bodies for their entire lives.

Pronghorns, however, shed the keratinous sheath from the bony core attached to their skull every year, usually after mating season has passed. These lightweight structures evolved to help pronghorns maintain their incredible speed. Males and females both carry these forked horns, but male horns are much larger while the female’s stay relatively short. Males also sport dark black fur on their cheeks and a dark mask that extends up their forehead.

Both male and female pronghorn are golden tan in color, with patches of white on their chest, stomach and rump. Their hairs are hollow and help trap in heat during cold winters.

Specialized muscles allow for full extension of the pronghorn’s body while in a sprint. Flaring nostrils and a large trachea connect to big lungs within a barrel chest that pull oxygen into the bloodstream. A sizable heart pumps oxygenated blood throughout the system to prevent overheating and sustain them on long, hard runs.

They are ruminants with a multichambered stomach, but this stomach system is smaller than those found in other species, allowing them to eat on the go. Pronghorn must constantly fuel themselves with high-energy forbs like sagebrush, willow and even cacti. They will also eat grasses when fresh and green. Much of their water actually comes from the vegetation they eat, setting them apart from similar nearby species like deer or elk that need to stop more frequently for water and cannot endure long-distance, high-speed chases.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention their large eyes, mounted on the sides of their head to monitor threats up to 4 miles away. Theories suggest that an ancient North American cheetah was once its greatest predator, but there aren’t any animals like that left to compete. Coyotes, mountain lions and even the stray wolf looking to chase down a meal are no match for the pronghorn’s speed. However, the young, sick and older members of a herd are always at risk.

Pronghorns are not especially long-lived, but females often have twin fawns born in spring. Groups of females will gather with a dominant male, and even larger herds will form during winter. Harsh winters and deep snows can pose a challenge for pronghorn, especially if they cannot move to new areas where food is readily available, temperatures are less frigid or snow is lighter.

Conservation Through Storytelling

One thing pronghorn bodies are not well suited for is jumping. One of the largest threats this iconic animal faces is fences and roads, which can restrict their migratory patterns.

For truly beautiful storytelling that follows pronghorn across fence-fractured landscapes, check out this short film “Under the Wire” produced by Platte Basin Timelapse. It is an amazing glimpse into the partnership between ranchers and storytellers searching to better understand the pronghorn and how to remove barriers to their survival.

Conservation work and storytelling like this go hand in hand. The science of a species is fascinating, but our heart connections to these animals also matter. The care we devote to them leads to positive outcomes for humans and entire ecosystems alike.

This grassland ghost is likely my favorite mammal found in Nebraska. Though their disappearing act in the middle of boundless prairie is mind boggling, I am content with brief, magical glimpses. I feel a kinship with them. I’m drawn to the golden yellows found in their fur and the landscapes in which they live. I love honing in on species that are weird and often overlooked. And I feel that I also thrive in the places where pronghorn are found, roaming gently rolling hills on the edge of a great wide open horizon under puffy white clouds.

May we all find some time to be more like the pronghorn. Soak up the sunshine. Move on when it’s time. Wander far and wide. Run fast when needed. Adapt to everything thrown our way. And proudly display that we’re all just a little bit weird.