By David L. Bristow, Nebraska State Historical Society

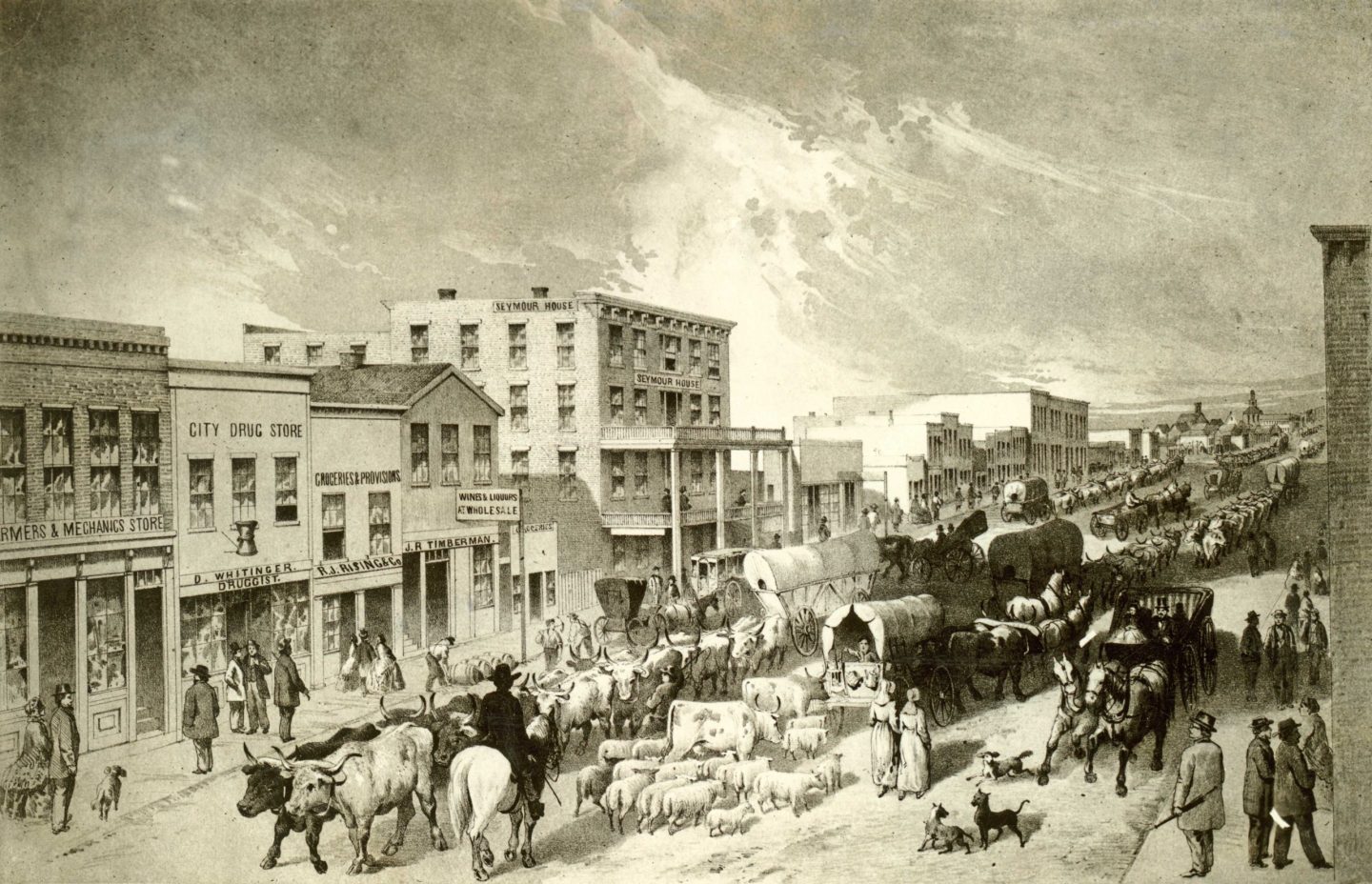

“There is heard the lumbering of these prairie schooners, the bellowing oxen — braying of mules, creeking [sic] of the long lariats, which for me is a show of itself to see the dexterity with which the drivers use them.”

So wrote a Nebraska City woman to her sister in 1866. She was describing the freight wagons crowding downtown streets. “There is the hollowing [sic], yelling of teamsters mingled with more oaths than I ever heard before in all my life together.”

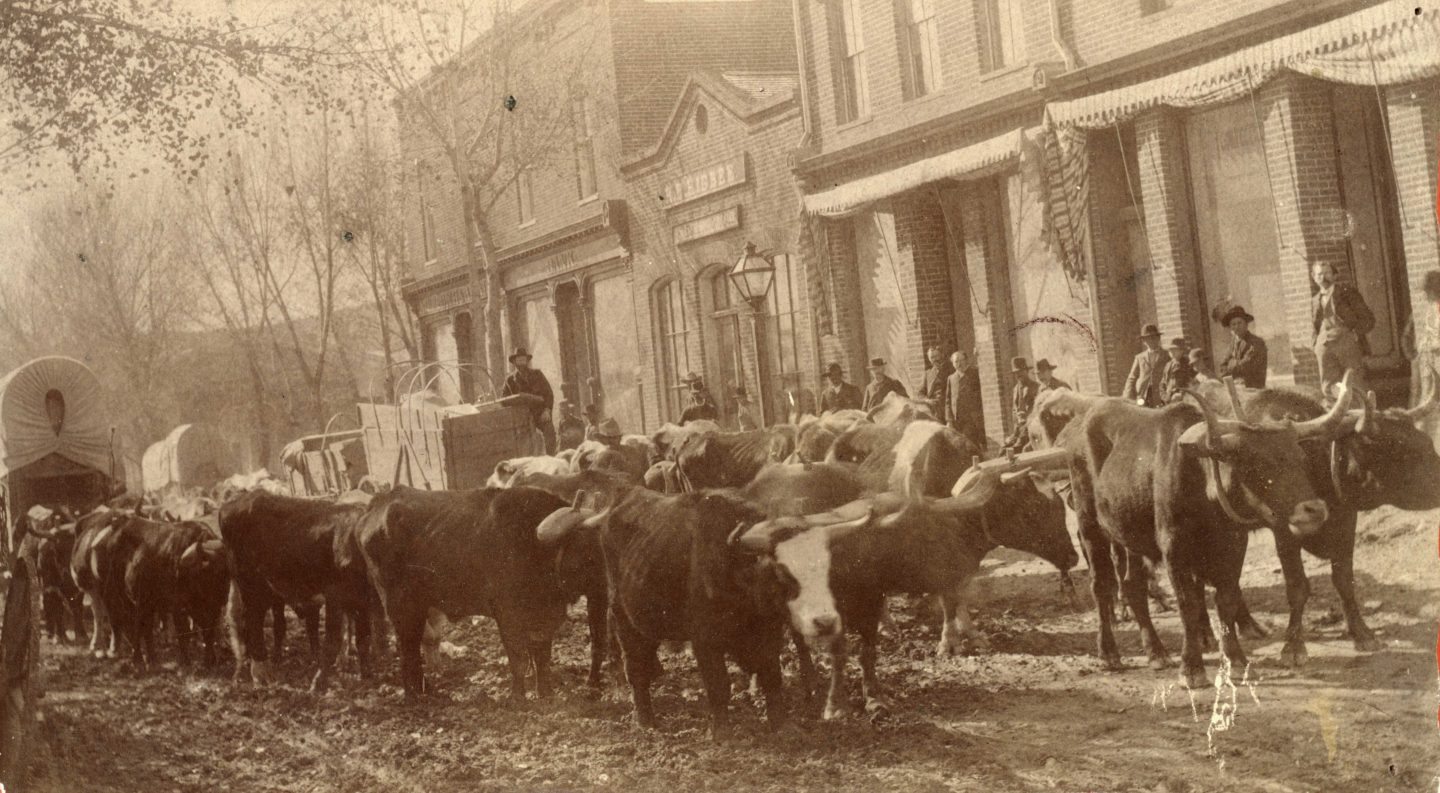

Not all the wagons crossing Nebraska belonged to would-be settlers seeking a new home. Prior to the development of railroads following the Civil War, teamsters drove thousands of heavy freight wagons from Missouri River steamboat landings to points farther inland. Nebraska City was the territory’s leading freight center in the early 1860s, followed by Omaha and Brownville.

While horses pulled freight wagons back East, on the plains a draft animal needed to keep up its strength on forage alone. According to William Lass — whose 1972 book, “From the Missouri to the Great Salt Lake” is still the best account of overland freighting in these parts — the choice was between oxen and mules. Oxen were relatively cheap, durable and less likely to stampede or be stolen, but mules were faster and more manageable. Driving a mule team required more skill, so “muleskinners” were better paid than “bullwhackers.”

But both classes of teamsters were considered dirty and disreputable. They usually wore broad-brimmed felt hats and red- or blue-checked flannel shirts, with trousers tucked into high boots and held up with a broad belt that also held a bowie knife and revolver. They rode all day in a cloud of dust and slept on the ground with no place to wash up. “No one,” said Lass, “except possibly buffalo skinners, had as much opportunity to become physically repulsive.”

A typical wagon train required about 300 oxen, 26 wagons and 30 men to haul about 60-75 tons of cargo. Doing so required physical courage and considerable skill. An ox-drawn wagon usually had six yoke, carefully arranged.

Out front, the two leaders were the best-trained pair, usually Texas longhorns. The strongest pair — the “wheelers” — were hitched next to the wagon. The next strongest pair were the “pointers,” hitched just ahead of the wheelers. In between the pointers and the leaders were the least experienced “swing cattle,” which were sometimes completely wild.

“The first pop I ever heard from the bull whip gave me a shock such as one might expect from the unlooked-for explosion of a cannon just a few steps behind you,” recalled Henry Palmer of his 1860 introduction to freighting. He said the whip was usually 12 to 16 feet long, and was used with precision by the bullwhackers, who were “not afraid of anything in this world or in the next.”

The teamsters circled the wagons at night to keep the animals corralled. Yoking them up in the morning was the most dangerous part of the day. Trails tended to follow rivers especially the Platte, so water was usually available — but former teamster Herman Lyon recalled that the trip to Denver included a waterless 40-mile stretch between Julesburg and Court House Rock. Considering that they made only about 12 miles a day, that was a considerable hardship.

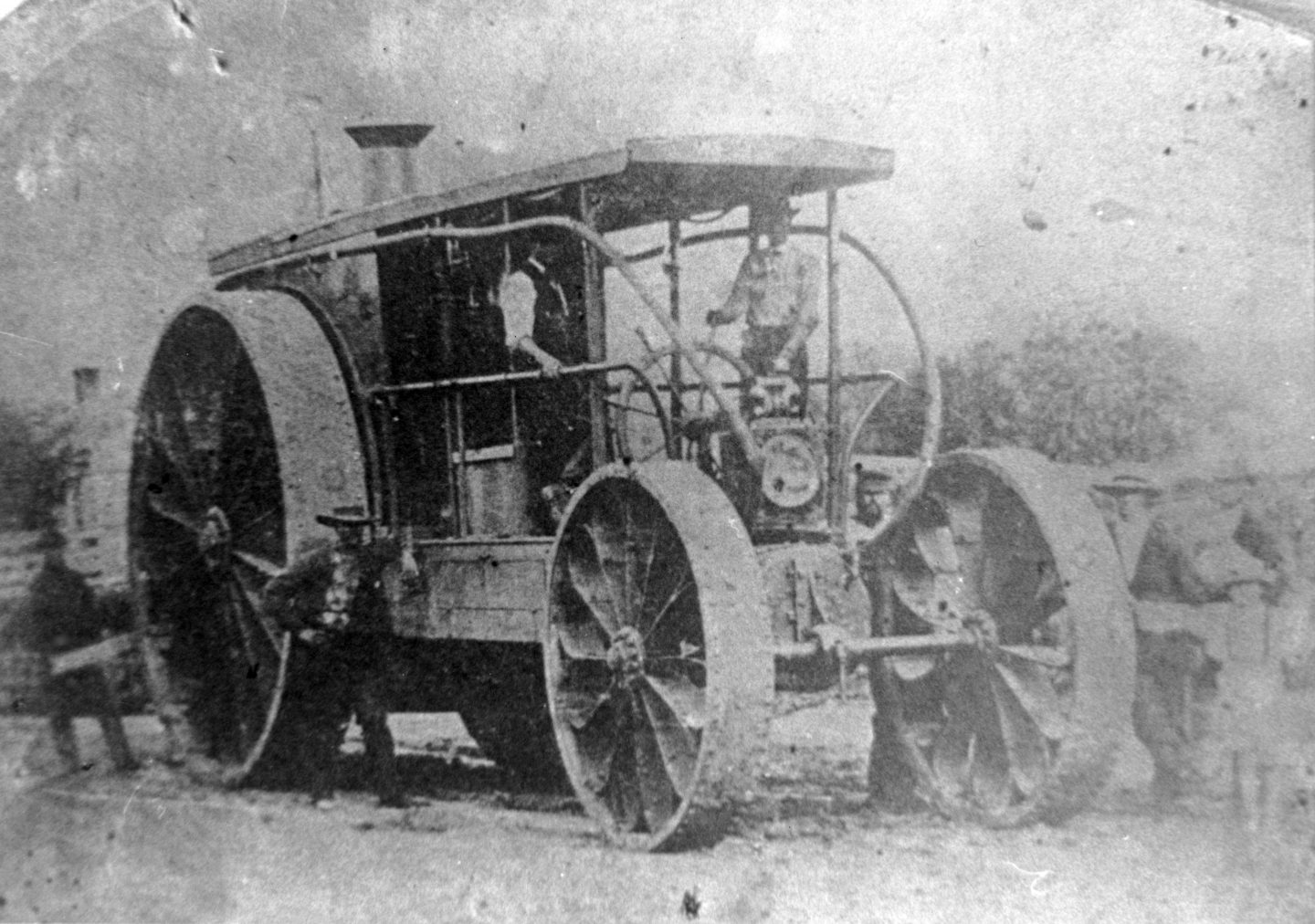

Naturally, entrepreneurs considered how new technology might change the game. What if you built a steam locomotive that didn’t need rails? In 1862, a New York City man named Joseph Renshaw Brown built a 10-ton “steam wagon” with rear wheels more than 10 feet in diameter. This monster departed from Nebraska City bound for Denver but broke down only 5 miles outside of town — a monument marks the spot.

The steam wagon was an idea ahead of its time. While the railroads eventually put the long-haul freight wagons out of business, the steam wagon was an early attempt to solve a problem later addressed by paved highways and semi-trailer trucks.

Visit NSHS’s website at history.nebraska.gov.