By David L. Bristow, Nebraska State Historical Society

“Rainfall follows the plow” is one of the most consequential ideas in Nebraska history. That doesn’t mean it was a good idea.

For centuries, Nebraska’s Native American inhabitants planted corn in the east and hunted bison in the west. When a U.S. military expedition crossed the region in 1820, the soldiers noted the lack of trees and the increasingly arid conditions as they moved west. After that, maps labeled the Great Plains as the GREAT DESERT. The region was “almost wholly unfit for cultivation, and of course uninhabitable by a people depending upon agriculture for their subsistence,” in the words of an early geographer.

As a result, the U.S. government was happy to leave the Great Plains as a permanent “Indian Country” into which displaced eastern tribes could be moved. But by the 1850s, the U.S. was planning to build a transcontinental railroad through that region and opened it to settlement. Following the Civil War, hundreds of thousands of settlers poured into the new state of Nebraska, pushing ever farther west into country with less and less rain. West of the 100th meridian (in other words, west of Cozad), rainfall averaged less than 20 inches a year. Good luck farming with that.

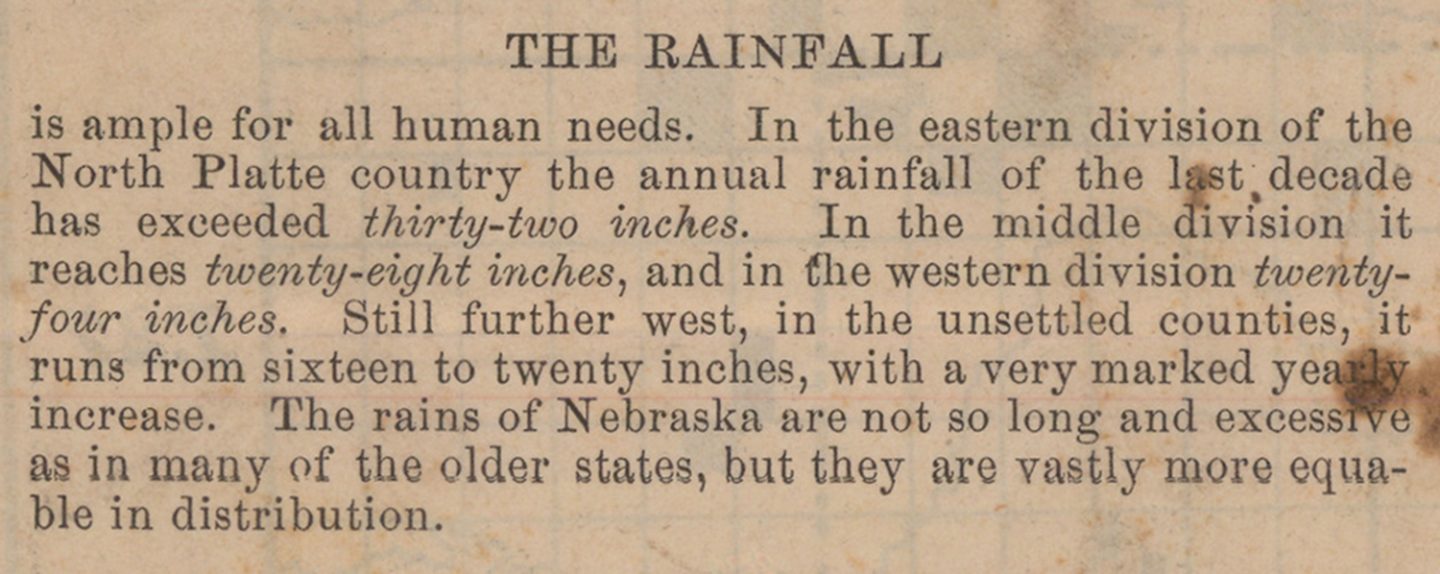

In 1880, a University of Nebraska professor named Samuel Aughey published a book explaining how plowing the prairie would allow rain to penetrate more deeply. Plowed land would soak up rain like a sponge. The broken sod would slowly evaporate moisture, which would create more rain. In the words of another writer, “rainfall follows the plow.”

Railroads and town boosters had a strong incentive to promote Nebraska’s land and climate, and they were enthusiastic for this new, scientific-sounding explanation. The Burlington and Missouri River Railroad even paid a stenographer to record Professor Aughey’s speeches, printing them as pamphlets to be distributed as far away as Europe.

And for several years in the 1880s, it all seemed to be true. Rainfall really did increase across Nebraska even as more land was plowed. A modern scientist would have warned people not to confuse correlation with causality, but nobody worried too much about that.

Then came the drought years of the 1890s, which were worse than anything most non-Indigenous people had seen. The new settlers hadn’t lived here long enough to know that such extremes are normal. And in many cases, they didn’t even know the area’s recent history. In his book “The Last Days of the Rainbelt,” geographer David Wishart writes that due to recurring drought, some parts of the high plains (including southwestern Nebraska) were settled and abandoned by “three or more waves of homesteaders before successful farming took root.”

Most of the Great Plains became cattle country. Successful farming in arid regions came only after the development of irrigation. Rain doesn’t follow the plow, but you might say the plow follows the center pivot.

Visit NSHS’s website at history.nebraska.gov.