By David L. Bristow, History Nebraska

On a clear, hot July day a haze came over the sun,” Addison Sheldon recalled. “The haze deepened into a gray cloud. Suddenly the cloud resolved itself into billions of gray grasshoppers sweeping down upon the earth. The vibration of their wings filled the ear with a roaring sound like a rushing storm. As far as the eye could reach in every direction the air was filled with them. Where they alighted, they covered the ground like a heavy crawling carpet.”

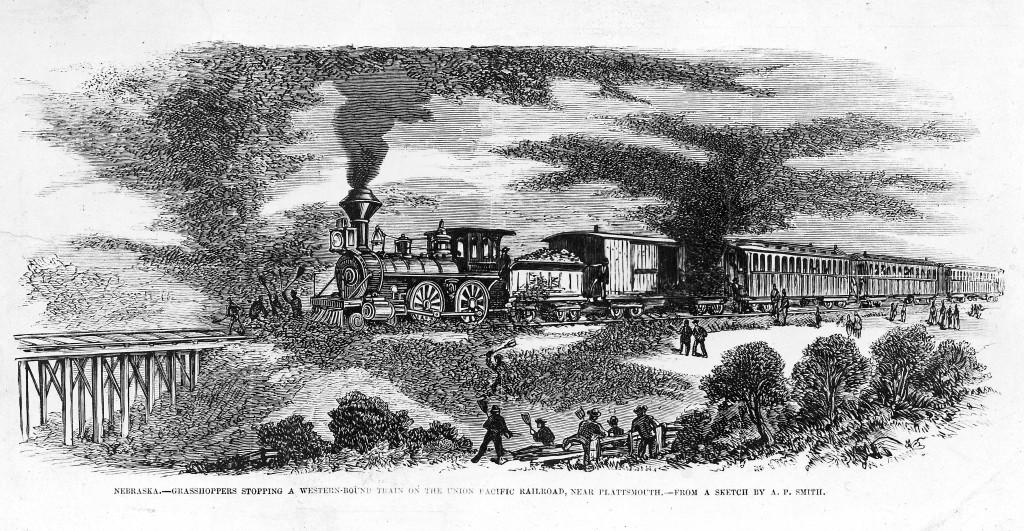

Sheldon, a Nebraska historian, was thinking back to when he was 13 years old during the severe drought of 1874. From July 20 to July 30, Rocky Mountain locusts (a species of grasshopper) swarmed over the central United States in numbers not seen before or since. From Minnesota to Texas, an estimated 12.5 trillion grasshoppers consumed every green thing in their path.

“In the hardest hit areas, the red-legged creatures devoured entire fields of wheat, corn, potatoes, turnips, tobacco, and fruit,” historian Alexandra Wagner writes in a 2008 issue of Nebraska History Magazine. “The hoppers also gnawed curtains and clothing hung up to dry or still being worn by farmers, who frantically tried to bat the hungry swarms away from their crops. Attracted to the salt from perspiration, the over-sized insects chewed on the wooden handles of rakes, hoes, and pitchforks, and on the leather of saddles and harnesses.”

The U.S. public responded with charitable donations, as it had done a few years earlier after the Great Chicago Fire. Using public funds for disaster relief was almost unheard of, Wagner explains, but private charity came with social stigma and strict conditions. Farmers seeking help from the Nebraska Relief and Aid Association had to swear that they had no money and nothing left to sell — not even animals or seeds — before receiving food assistance.

In November, Army Major N.A.M. Dudley warned his superiors of appalling conditions he had seen in southwestern Nebraska:

“Relief must be given these people or hundreds will starve before the winter is half over … The present aid they are receiving is only a drop in the bucket.”

The region’s newspapers had been downplaying the disaster, not wanting to discourage immigration to the Great Plains. Now the Omaha Daily Republican estimated that 10,000 Nebraskans were in danger of starvation. At last, state legislatures and the U.S. Congress began appropriating funds for food, clothing and seeds for the following spring.

Rocky Mountain locusts returned in other years, but the expansion of farming so disrupted their habitat that the species became extinct by the early 1900s.

Wagner argues that grasshopper relief efforts helped establish federal and state government roles in disaster relief and in aiding agricultural producers. Those expectations developed over the years, but 1874 arguably marks an early turning point. You could say that grasshoppers helped shape the world we live in today.

Read Alexandra Wagner’s complete article by searching for “grasshopper” at history.nebraska.gov.