Enlarge

Story and Photos by Justin Haag

Heavily marred with dirt, dings, scratches and rust, it did not look like much. Despite its condition, I knew the item handed to me — a Stevens Springfield 87A .22 semi-automatic rifle — was a special gift.

I best remember the gun from my childhood in southwestern Nebraska in the 1980s; it hung on the rack in Grandpa Alfred’s beat-up green Ford as it was parked at his and Grandma’s service station on Danbury’s main street. Resting in the rear window, the rifle was always at the ready during his evening trips to the farm, his boyhood home 4 miles north of town.

I was fortunate to be passenger on many of the daily trips to the place where he and my dad were raised, and have memories of Grandpa teaching me how to use the rifle at a nearby prairie dog town.

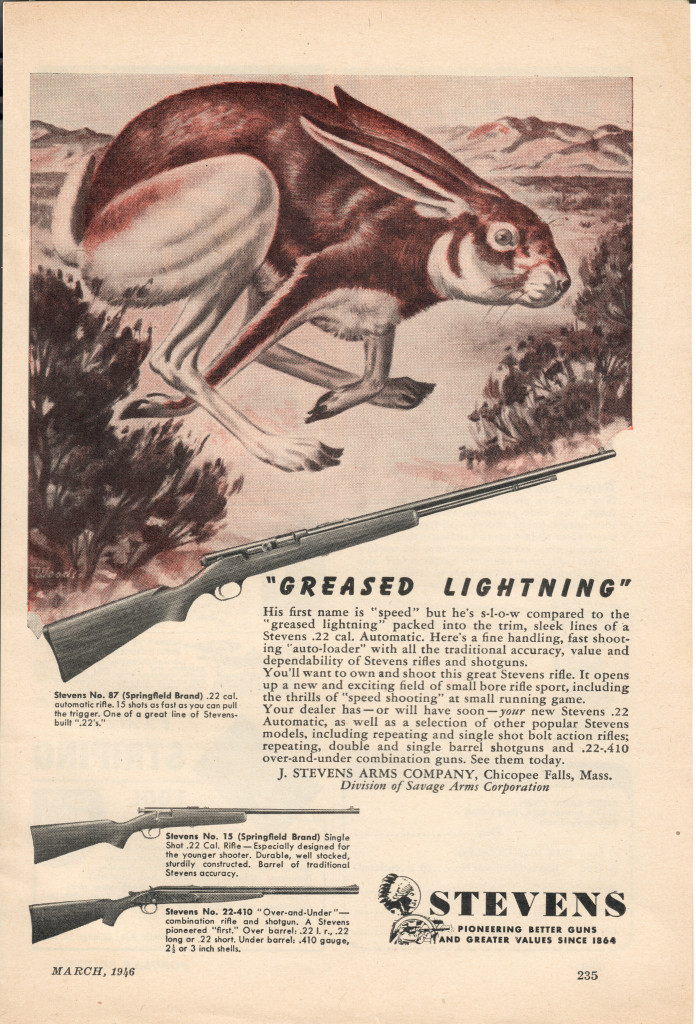

Rifles such as this were not required to have serial numbers until 1968, but the barrel has one patent number; resources indicate it was manufactured in the model’s first three years of production, which began in 1938.

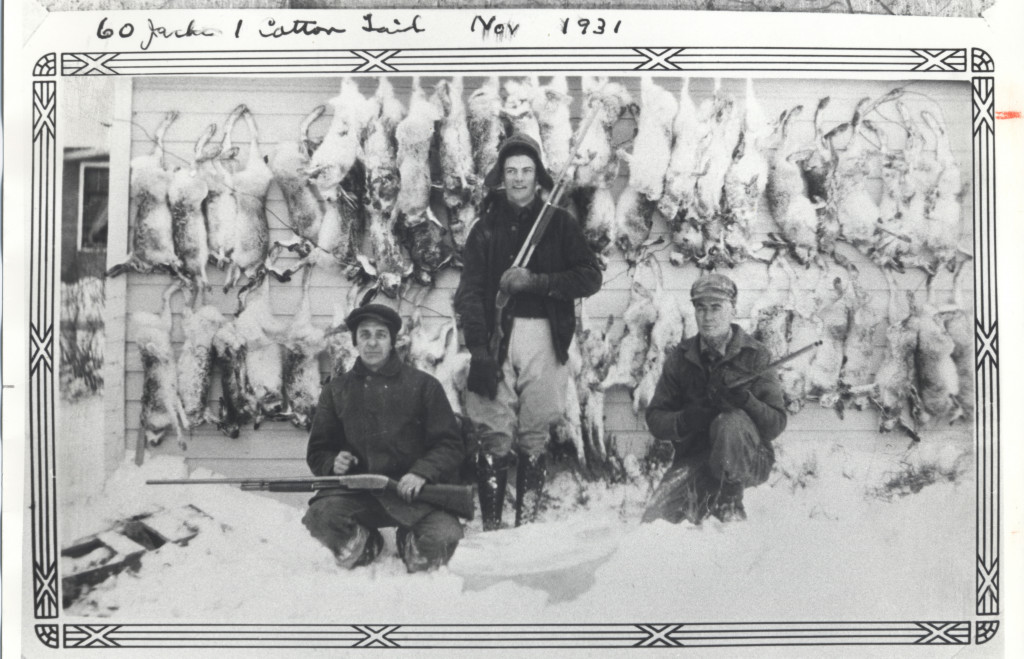

Grandpa often told of how the gun paid for itself in jackrabbits in short time. Considered an overpopulated pest during the Dust Bowl of the 1930s and into the 1940s, many counties offered a bounty on the long-legged, hungry grazers. A newspaper article from 1940, when Grandpa was 19, tells of the McCook rendering plant paying 5 cents per jackrabbit. An advertisement from that year shows the gun could be bought for $11.61. So, cost of ammunition aside, I figure that’s about 232 jackrabbits.

As one of more than a million of this model Stevens sold, the firearm — one of the first mass-produced semi-automatic .22s — is far from being a rarity.

I could not even guess how many rounds it has fired. It helped put food on the table for my grandparents when they were newlyweds. Long before I took aim with it, and years after those jackrabbit harvests, my dad and uncle remember it entertaining the family as a plinker around the farm — especially on the many nights the TV’s one station was on the fritz. They say one of Grandpa’s favorite activities was lighting and extinguishing matchsticks with a careful aim. If the farm’s varmint population needed to be curbed, it was the go-to tool. During wheat harvest, it rode on the combine. Despite heavy use and minimal cleaning, Dad says he cannot remember it ever jamming or misfiring.

As Grandpa aged, the rifle was put into storage with his other guns. Sometime after he died in 2001, they were passed on to family. I decided to clean the Stevens well enough to stop the rust and keep it as a conversation piece. Beyond that, I had little optimism about its future.

After inspecting it, though, I was pleased to find the bore free of rust and corrosion, as were all of the mechanics of the trigger and bolt assembly. A few blasts of an aerosol gun cleaner had those parts moving well and looking fresh again. All of that Red Willow County dirt came off easy enough, and the rust on the exterior of the barrel and magazine relented by rubbing it with fine steel wool and oil. After cleaning and oiling, I put the gun in the cabinet. It stayed there for more than a decade.

This winter, while giving guns a routine cleaning, I decided the rifle deserved better.

I am certainly no gunsmith, but after reading message boards and watching how-to videos online, I gained enough confidence to tackle a more thorough restoration. As a weekend do-it-your-selfer, I already had the necessary tools, and the refinishing products were easy enough to find at local retailers and online.

A special cleaning solution helped remove the little bit of bluing that remained on the barrel, and a fine wire brush on a rotary tool helped clean the tight spots. After getting that maltreated steel to shine, I was amazed at how a liquid cold-bluing solution returned it to an attractive black in a matter of seconds.

A hot iron over a damp rag lifted many of the dents from the stock, and deeper gouges and scratches were filled with a putty of wood glue and sawdust, the latter of which was harvested by drilling a hole under the butt plate. After sanding the surface smooth, multiple coats of gun stock finish made the wood shine. Below the glossy finish is evidence of all those dents and dings, but they somehow add a richness and beauty to its one-of-a-kind appearance that only decades of abuse can provide.

The rifle is not only a conversation piece, but also a firearm I am proud to carry. What’s more, I have found it to fire as reliably as it did when aimed at those hordes of jackrabbits of the ’40s.

Advertisements from when the rifle was new boast not only of its craftsmanship and affordability, but also its speed and three-in-one design. It will fire as not only a semi-automatic, but also a single-shot and bolt action. I became familiar with each part of its action throughout the refinishing process.

With the stamping of “Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts, USA” on top of the barrel, the Stevens Springfield 87A was born in a different era of the American economy. Even though it was one of the least expensive rifles available, it has a quality of construction present only on high-end firearms of today — a collection of sturdy, machined, U.S. steel parts assembled on a bed of birch, presumably harvested in New England.

I did have to replace the stock’s butt plate, the only piece of plastic on the entire rifle. Extremely brittle, it shattered when I fumbled it to the hard basement floor. Thankfully, I located a replica from an online retailer.

Perhaps I would have been better off hiring a professional gunsmith, who surely would have done a better job returning the rifle to near mint condition, without dropping any pieces. That is not my style, though. Nor my grandpa’s. There is much reward in doing the project myself, and I am glad there are still a few remnants of the rifle’s many battle scars.

While I consider the rifle a treasure, I will not be hocking it to embark on a lavish lifestyle. Rusty relics in this one’s previous state often sell for a low bid at farm auctions. Even in pristine condition, they do not fetch much more than $150.

To me, though, it is invaluable. It is an heirloom that bridges generations and honors the past. Every time I shoulder it, my hands grip the same places my grandfather’s did. Also relatable, my eyesight has degraded to where I complain about the rear sight being a little blurry — just as I remember him lamenting at that prairie dog town in the ’80s.

Sadly, Grandpa and the old Ford are gone, the gas station’s closed, and the old house and other farm buildings are in disrepair. The state’s jackrabbit population is scarce. The rifle, however, endures.

Surely many modern .22 rifles are much more highly regarded than this one, but, lacking American artisanship from the 1930s and ’40s, I wonder if they will stand up to decades of such use and abuse. If the objectives are durability and reliability, I will place bets on Grandpa’s timeworn, but reborn, American-made Stevens Springfield. ■

Nebraskaland Magazine

Nebraskaland Magazine