Enlarge

By Allison Barg, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Research Graduate Assistant

“I put pheasant habitat on my property. Why don’t I have any pheasants?”

University of Nebraska-Lincoln biologists are trying to answer this question. Many Nebraska landowners and wildlife managers have noticed that in parts of the state where there are swaths of land covered in what looks to be ideal pheasant habitat, there are no pheasants. It turns out that the “if you build it, they will come” approach doesn’t always work with wildlife.

Nebraska is 97 percent privately-owned and dominated by agriculture. The majority of pheasant habitat we do have is the result of the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) and other similar programs that pay landowners to take acres out of production and convert them to native grassland. Since its inception in 1985, this system has had huge benefits in improving natural ecosystem functions and improving wildlife populations. Still, despite wildlife managers’ best efforts, pheasants continue to decline.

In an ideal world, we could fix this problem by just adding more habitat. But in the real world, we are limited by funding sources and competing land uses (i.e. agricultural production), which means that the overall amount of land that we have for wildlife habitat isn’t likely to increase by a whole lot. To help maximize future conservation efforts, my research will focus less on the amount of habitat on the landscape, and more on where that habitat is located – a “where should we build it so that they will come?” approach, if you will.

To begin my research, I had to first identify where pheasants are currently thriving and why. What factors are driving pheasant populations to thrive in certain areas and faltering in others? These questions can’t be answered by sitting in a lab. Field work is an important component of what Nebraska wildlife biologists do, and my hope is that this four-part series will give you a glimpse of what wildlife research looks like, while hopefully providing answers to our pheasant conundrum at its conclusion.

What is Field Work?

Mention the words “field season” to any ecologist and you will probably be met with equal parts excitement and dread. For many of us, this is the absolute best part of our year – and the most stress-inducing. Field work generally refers to the portion of a research project when we are actively collecting data in the field, as opposed to interpreting data in a laboratory. In biology, field work is often time-sensitive, as we are at the mercy of whatever biological system we are studying. In my case, the best time to count pheasants is during the spring mating season when males will “crow” at regular intervals throughout the morning. This means that the only time I have to collect data is from about 5:30 a.m. – 8:00 a.m. on calm, dry mornings in April and May.

Let me repeat: “calm, dry mornings in April and May in Nebraska.” Needless to say, field work is a bit of a mad dash to collect as much data as possible, as quickly as possible, while the weather holds. Here is what that mad dash has looked like for me this week.

Monday, April 11, 2022

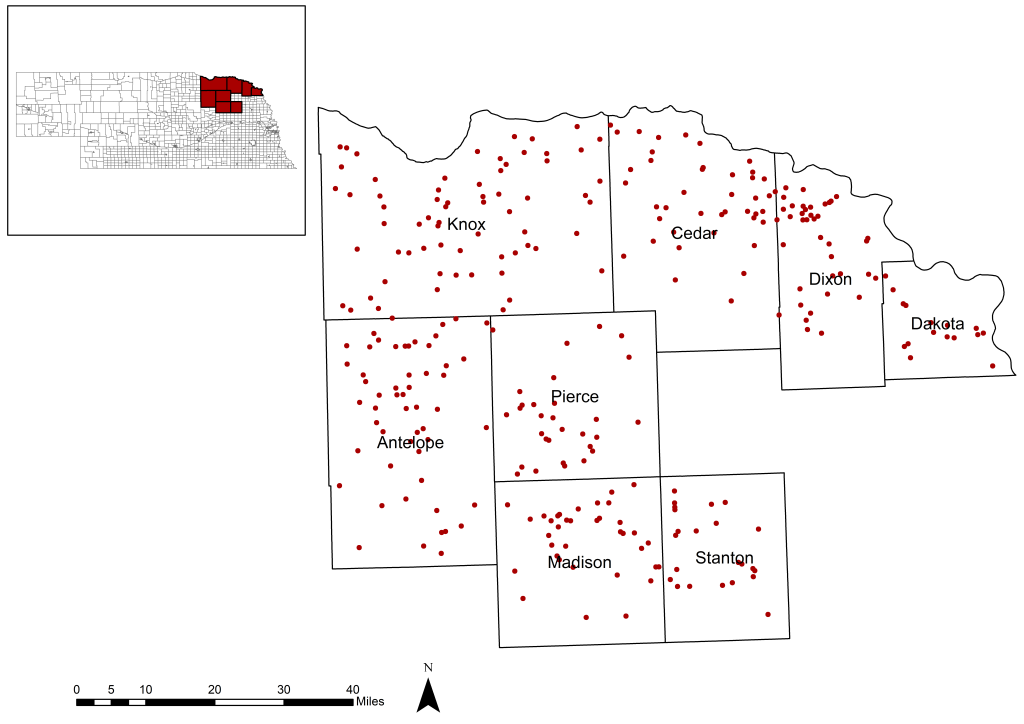

To set the scene, I have two different study areas for this project. The first area covers nine counties in the eastern portion of the Rainwater Basin in south-central Nebraska, and the second covers nine counties in northeastern Nebraska. I am currently working in the northeastern study area, based out of Norfolk.

4 a.m. – Crow counts run 1 hour before sunrise until 8 a.m., and this morning, sunrise was at 6:52 a.m. Today, I’m running counts in eastern Dixon County – as close to South Dakota as you can get without actually crossing the border – which is about an hour drive from my hotel, so I need to leave by 4:52 a.m. And because time for breakfast and coffee is an absolute must, I’m up at 4 a.m.

4:50 a.m. – I grab my binoculars and clipboard, turn on my audiobook, and I’m on the road with two minutes to spare.

5:45 a.m. – Pulling up to my first point, I am faced with a “bridge out” sign. A “point” refers to the spot that we conduct a count. These points are randomly selected before field season and capture a variety of habitat characteristics in the surrounding landscape. All points are located on roads, so we don’t have to access any private property.

Unfortunately, when generating point locations in Dixon County from a computer in my office in Lincoln, it is impossible to tell which of these locations are actually drivable just by looking at a spatial layer of “roads” on a screen. This one is obviously not, at least not from this side, and since it is still dark, I decide to leave it for the time being. I’ll move on to some other points and come back in the daylight to see if there might be another way to access it.

6:10 a.m. – This is my favorite time of day. I can just barely make out the start of the sunrise. The birds are starting up, and pheasants are in full crowing mode.

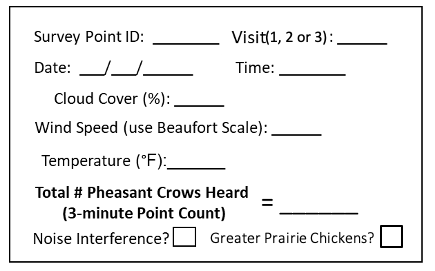

The next point where I will be counting is just on a regular gravel road, so I pull off to the side, park the truck and get my datasheet ready. At each point, I record the point number, date, time, wind speed, temperature and percent cloud cover. Then I get out of the truck very quietly and set my timer for three minutes. Previous pheasant studies using this method have found that an individual male pheasant crows, on average, once every three minutes. This means that we can assume each crow within a three-minute time frame is a unique pheasant.

7:10 a.m. – Slight delay due to a loose cow on the road! Thankfully, the farmer was already there. While a nice stranger and I blocked the road on either side so the cow wouldn’t run into it, the farmer guided the cow back into the fenced-in field.

7:45 a.m. – I’ve made it to 10 points so far this morning, which is about average. So now I head back to that first point where the bridge was out to see if I can access it from the other direction.

7:55 a.m. – OK, theoretically, I can drive to this point. The road is there. But it is so steep and narrow that I’m hesitant to take my brand new, University-owned field truck over it and find out that I can’t get back down. This is a unique problem for someone from southeastern Nebraska, where we don’t often have to worry about hills. So, looks like I’m walking it! Who doesn’t love a nice morning walk on a sandy, minimum-maintenance road?

Tuesday, April 12, 2022

There’s wind advisory. Crow counts are dependent on being able to hear pheasant crows, and in high winds, our ability to hear becomes limited. Additionally, pheasants may be less likely to be out feeding, and therefore crowing, in poor weather conditions. So, today will be an office day, it seems.

Wednesday, April 13, 2022

Another wind advisory.

Thursday. April 14, 2022

And another wind advisory …

Friday, April 15, 2022

4:00 a.m. – AND WE’RE BACK! Heading in a different direction today, up to Knox County. Still about an hour drive, so once again, I’m up and ready to head out bright and early.

6:30 a.m. – I’ve managed to hit four points so far, and the morning is going well. The challenge I’m having today is that many of my points are surrounded by trees, and I can hardly hear myself think over the sound of the red-winged blackbirds. On the datasheet, we have a check box for “noise interference,” which will show us during analysis that there may be outside noise affecting our ability to count. The purpose of that box was to account for things such as traffic or nearby farm machinery. But the most common reason we check it? Other dang birds.

1 p.m. – I finished my points for the day, made it all the way through the other work I needed to do and got halfway back to Norfolk before my low-tire light came on. That low-tire warning quickly became a completely flat tire near Laurel. Oh, the joys of field work! But actually, it’s a best-case scenario — the tire is still attached, which has not always been the case in past field experiences, and I’m actually in a town — a rare occurrence — which means roadside assistance can find me easily and I can get lunch while I wait.

5 p.m. – It took a few hours, but roadside assistance got my tire changed. Got the truck fixed up and back to Norfolk. Time to enter data and get ready to do it all again tomorrow. Well, hopefully not all of it.

Read Part II: https://magazine.outdoornebraska.gov/2022/05/a-researchers-field-season-part-ii/

Read Park III: https://magazine.outdoornebraska.gov/2022/06/a-researchers-field-season-part-iii/

About Allison Barg

Allison grew up outside of Mead, Nebraska, and received her bachelor’s degree from the University of Nebraska – Lincoln in fisheries and wildlife in 2016. After several years working on research projects on everything from bats to sea turtles, she returned to school to earn her master’s degree in wildlife management and conservation from the University of South Wales. Allison’s master’s research was based on western polecats and their interactions with road systems. In 2021, Allison moved back to Nebraska to begin her PhD at UN-L where she works in the Applied Wildlife Ecology and Spatial Movement (AWESM) Lab.

Allison grew up outside of Mead, Nebraska, and received her bachelor’s degree from the University of Nebraska – Lincoln in fisheries and wildlife in 2016. After several years working on research projects on everything from bats to sea turtles, she returned to school to earn her master’s degree in wildlife management and conservation from the University of South Wales. Allison’s master’s research was based on western polecats and their interactions with road systems. In 2021, Allison moved back to Nebraska to begin her PhD at UN-L where she works in the Applied Wildlife Ecology and Spatial Movement (AWESM) Lab.

Nebraskaland Magazine

Nebraskaland Magazine